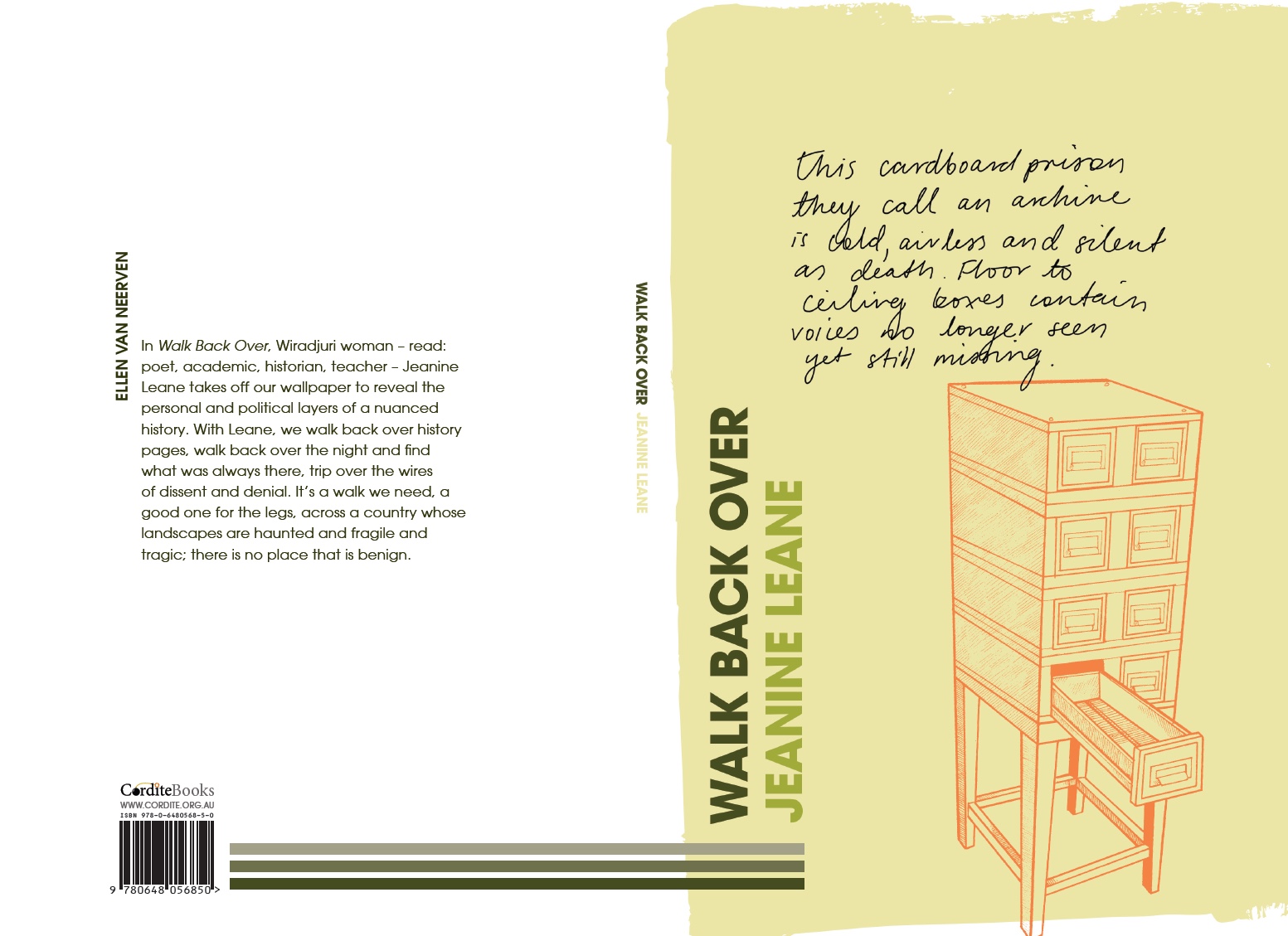

Cover design by Alissa Dinallo, Illustration by Lily Mae Martin

In Walk Back Over, Wiradjuri woman – read: poet, academic, historian, teacher – Jeanine Leane takes off our wallpaper to reveal the personal and political layers of a nuanced history.

With Leane, we walk back over history pages, walk back over the night and find what was always there, trip over the wires of dissent and denial. It’s a walk we need, a good one for the legs, across a country whose landscapes are haunted and fragile and tragic; there is no place that is benign. ‘What piece’ (what peace)? – the question asked in the second poem, ‘Piece of Australia’ – becomes an echo in the reader’s mind throughout the collection.

We know the past speaks, and Leane personifies history. Lady Mungo has a voice, the archives have a voice, the ancestors have a voice. She grew up in Gundagai in the Wiradjuri (meaning: of the rivers) nation in central New South Wales and her Country and the legacy of the women who raised her on it are central to her vision of Australia.

Walk Back Over is an accomplished poetic dissection of the country’s problem – an embodiment of an inability to move on from a colonial terra nullius mentality that minimises massacres and denies the theft of land. We represent communities still looking for lost ones. Trauma is in many rooms and still we survive. To demonstrate this, Leane shows the personal effects of assimilatist policies. In ‘Real Australian girl, 1975’, the young narrator pictures conforming her body for the white gaze in visceral terms ‘… a fillet knife / slicing through those thick lips until they are / wan, white and bloodless like Friday fish’. This is matched with the resolute, defiant identity: in ‘Unassimilated’, ‘Your assimilation failed to break / black lines flowing from the heart / my Grandmother, my Mother, Me, my Children.’ A desire grows to put them, the colonisers under the microscope – we’ve been under there too long.

Hot water is always hot. It keeps being refilled. The words continue to be direct, calm and clever. The timing and sequencing delivers, the collection flows and ebbs like – I imagine – the author’s often-mentioned ancestral Murrumbidgee River (a life source, a document) used to before white intervention.

Leane continues to question what is ‘outside history’ in poems about visits to other countries. Like the beautiful ‘Sunrise to Sunset in Yangshuo’, where the narrator moves with the sun through the city and does not drop her gaze. I will return often to this scented writing. When we absorb knowledge, we become larger.

Close to the end, tenderness comes in. Through the length of the collection, Leane has carved a hole in the rock of us and that’s where I have saved my tears, for they are gathered in the tiny pool of a beautiful poem, ‘Child’, about the relationship between mother and son and the slippage of time. ‘You clung to my hand like / I knew the world.’ The emphasis on love in Walk Back Over brings a reminder of responsibility. If you love this country, truly love it, understand what has been taken, talk about it, don’t flinch, don’t cover your eyes.