Caren Florance works in the Venn overlaps of text art, visual poetry and creative publishing. Her work is hard to pin down, principally because the artist herself is not interested in a static outcome. Much of the work appears as a flux, a process or a continuum along a moving line that often explores language and our usage of it.

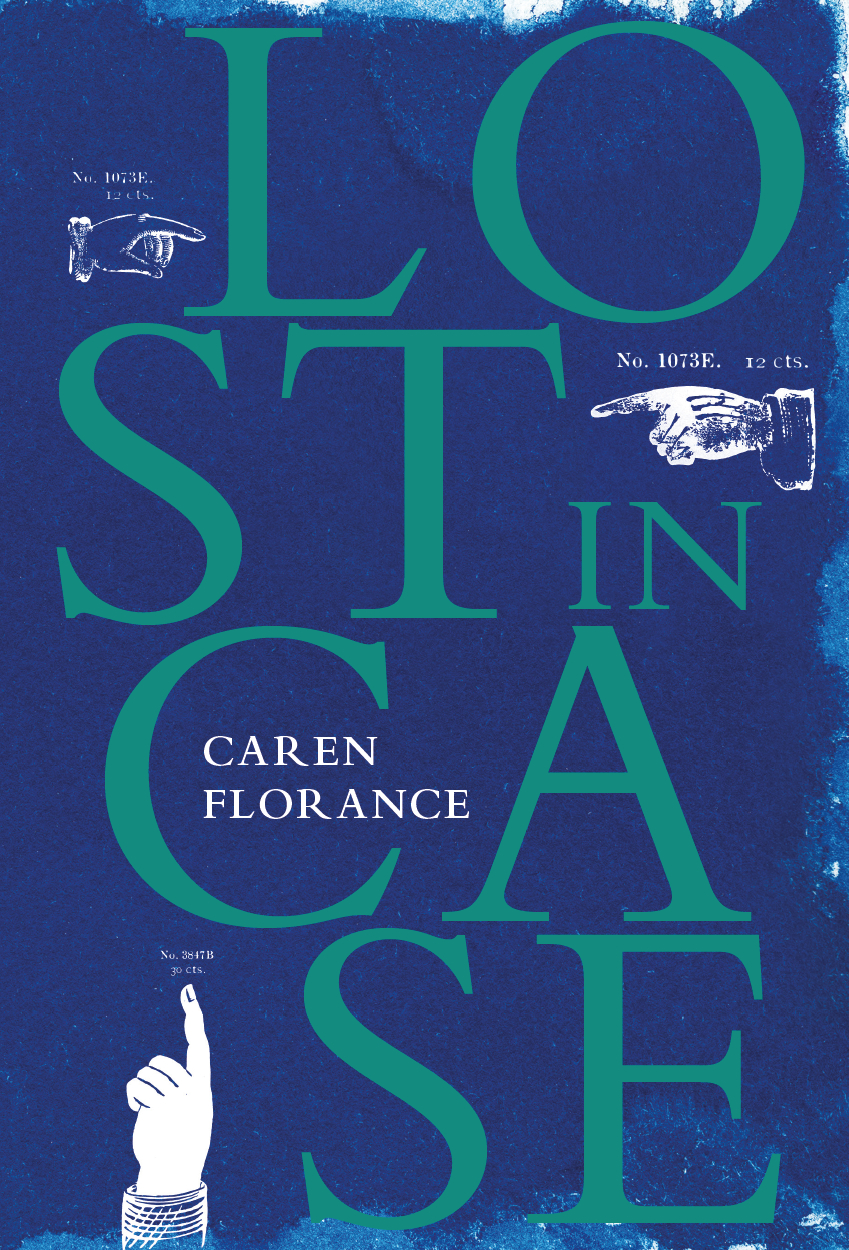

Take letterpress – the method of using moveable type to print multiple copies. In some of Florance’s work, the letterpress is not even printed as words (the expected or usual outcome of ink on paper, or at least ink on printable surface). Instead, what you see is the process of arriving (or not arriving) at the print. The California job case holds individual pieces of moveable type: there is one rectangular box for each letter, each space, each mark of punctuation. As the hand reaches across the case to pick each piece from its box, lines of movement are created. These lines are recorded by Florance with drawn lines: in this book, words are substituted for diagrams of movement.

As readers of these visual poems we are slowed down so that the meaning embodied in the method itself is made visible. A space in this system, for instance, has weight and heft, it is a metal piece that has its own positive presence in the type case. You reach for it as you would the space bar on a Qwerty typewriter and it yields the same result: a nothing that is a something, between other somethings. The typist knows the work of reaching for and touching that space; the reader, in the rush to get to the meaning, may forget.

Language is performative, and the words Florance has chosen to work with in Lost in Case have particular meanings and histories. Many are drawn from vocabularies of abuse, or shaming, of female bodies, or commentary on the availability of those bodies for the sexual use of men. The language is brutal and is taken from spaces that have not been friendly towards women: from misogynist male-only forums to incel chat rooms, for self-identified and angry involuntary celibates. With autonomous AI-informed sex-bots on the horizon, issues of determination and consent will continue to be foregrounded. Will a compliant human-like sex toy serve to reinforce the mistaken entitlement of the incels?

Using these words here is not self-abuse. Instead, Florance counters sloppy online reasoning, which seems to elide issues of self-determination and consent, with a rigorous analogue Teknik. She takes control of the gestures behind the words, to render the abuse as visual poetry. Florance’s aim to transmit the words again without reseeding their message is, in her words, ‘a cathartic act of feminist disruption’. Working from a theory of forensic materiality – informed by the work of academics Matthew Kirschenbaum, Jerome McGann and N Katherine Hayles – Florance makes something that seems impenetrable and lost to meaning able to be translated by forensic means. The word ‘forensic’ reminds us that words have heft, they take shape. How should we react to these words? Instead of allowing misogynistic language to proliferate in the self-reinforcing echo chambers of online forums, we must take it out into the light and examine what animates it. For some women this will become a matter of life or death.