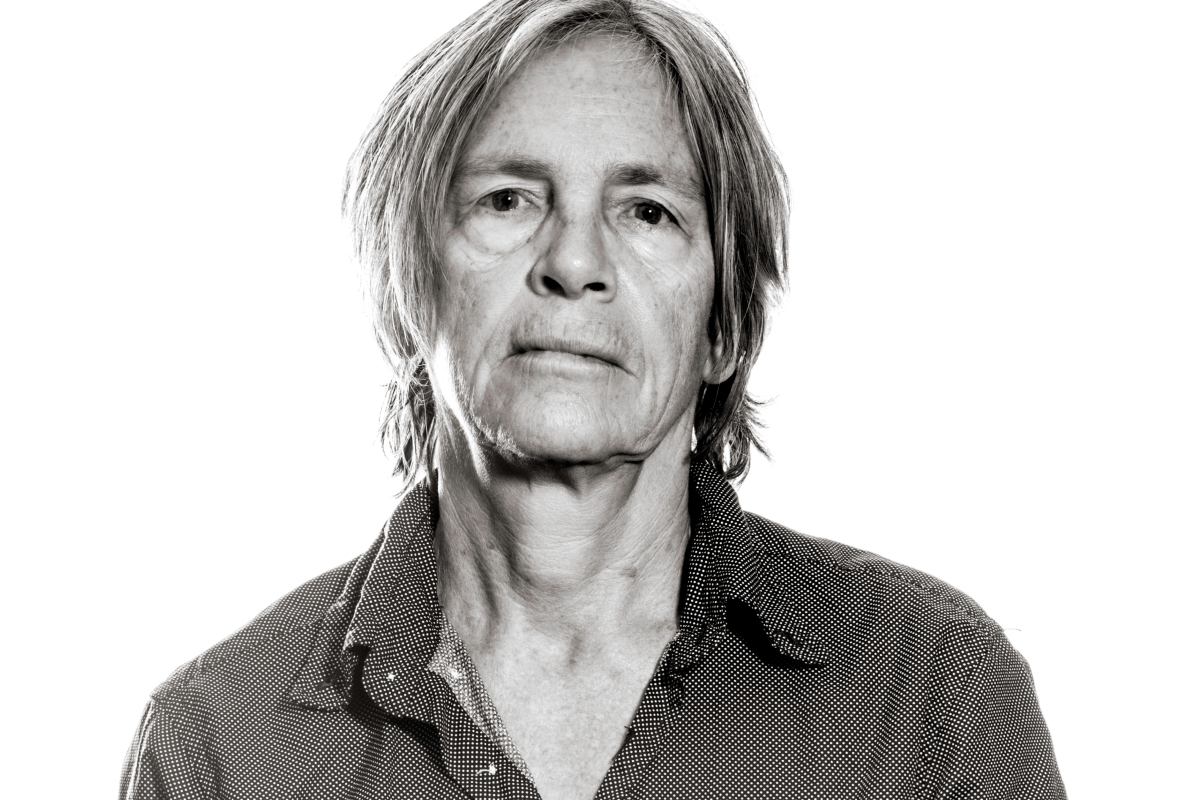

It is difficult to interview someone with a career spanning approximately forty-five years and an oeuvre that has profoundly affected me. It is also difficult to introduce them to an audience of readers, so I will set the scene instead: Eileen dons a blue t-shirt and sits on a spinning office chair in front of a large whiteboard with visible notes on it. Glasses on, they scratch their head occasionally and rest their chin in their hand. Eileen was born in 1949 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and lives in New York and Marfa, Texas. They’re a poet, novelist, and art journalist and remain one of the most recognised writers of their generation.

Conversing is also, somehow, one of the most difficult things for two people to do together – language can fail us, then carry us, then fail us again. When trying to find something smart to say about disfluent speech, as it so often presented itself during my conversation with Eileen (particularly when discussing mothers, death, and ex-partners, i.e., love and pain), I stumbled across a paper titled ‘Stuttering From the Anus’. The author, Daniel Martin, argues, along the lines of Freud, that disfluent speech comes from unresolved neuroses stemming from the anal stage of human development. Eileen kept saying, You know? And repeatedly false-starting. I kept stuttering: I … I … like … and yeah … like … It reminded me of a conversation between two characters in a Dennis Cooper novel. Our conversation was subsequently edited for readability purposes, but it feels important to tell you, as you may sense the disfluencies regardless.

We spoke together in late August (I was in Paris and Eileen in Marfa) for just over an hour about the late Etel Adnan, the ongoing genocide in Gaza, love poetry, painters, smoking and not smoking cigarettes, France, butcher markers, Eileen’s forthcoming novel, Pasolini, writing about people you know and believing in someone ‘like a door that returns.’

Sophia Walsh: It’s such a scary voice, ‘The Zoom.’

Eileen Myles: I know, I know. Who is she?

SW: Do you think she’s real, or is it just an AI?

EM: I think she’s somebody. I think somebody got the job originally and they’ve just done things with her voice forever.

SW: I wonder how she makes her voice sound like that. It’s terrifying. I’ve ever only recorded one Zoom session once in my life, and I can’t remember if it was recorded.

EM: Do you want me to put my phone on to record it, just in case?

SW: Oh, you don’t have to do that …

EM: Hold on, one second.

[Eileen gets up and walks away from the screen, returning with their phone to record.]

I always require somebody else’s intervention.

SW: How’s Marfa? Is it cold there?

EM: It’s good. It’s really perfect right now. Last month, it was incredibly hot, and now this month, it’s cool, not too cool, but it’s down 10 or 15 degrees, and it’s much nicer.

SW: Is there really a winter there?

EM: I mean, it’s like light snow, it’s the high desert. Texas has snow and cold weather. It’s tropical, but it’s not hot like Arizona. Parts of it are hot and humid. It’s like Santa Fe, so it’s cool in the morning, cool at night, and then hot during the day. It’s nice.

SW: Have you been there for most of the winter?

EM: This year, I sublet my apartment in New York to work on a book. And so, I came here in January, and I guess when the year is over, I’ll have been gone for like three months.

SW: I wanted to talk about Etel Adnan. I didn’t attend the event [‘Books That Matter: The Perpetual Present of Etel Adnan’ for the Fine Arts Work Centre on 4 June]. Did you read the whole The Arab Apocalypse poem?

EM: No, I just talked about it. I know the event was weird because I teach at that place. They had to come up with something for people who weren’t teaching to have a one-day gig, and of course, they wanted to make money for this reason. So, the deal was, we were splitting the money, but then it was quite expensive for people to attend, and then I had to contact all these friends and say, ‘You know, write to me if you want to attend and get the discount.’ So, it ended up excluding many people, which was a drag. Mainly because, at this time, there’s very little I feel comfortable doing without talking about Gaza at some point. And so, I could have used any book, but asking people for a lot of money for any book seemed stupid. So, I picked Etel Adnan and found the right book, and then after the event, I gave half of my money to Gazan orphans. When doing so, I thought nobody would know I was doing this, but I needed to.

SW: Do you have a physical copy of The Arab Apocalypse?

EM: I have both the PDF and the book. Have you read it?

SW: I still need to finish it, but I have it open on my laptop, just in PDF form. But I thought seeing a hard copy of the physical book would be beautiful.

EM: I have it in someplace. Give me one second.

[Eileen gets up and walks around to look for the book.]

I’ll send you a picture when it does turn up.

SW: I was interested in how the glyphs look on the page and their spacing.

EM: Well, just like identical to what you see on the PDF, right? What’s interesting is that she wrote it by hand. Initially, the glyphs and the text were in the same hand, which is important.

SW: Do you have the translated English version? [Adnan wrote the original in French.]

EM: Yes, and it’s handwritten and typed. Her partner, who’s still alive, published it. It’s a Litmus Press, an American press. They shepherded it into the world.

SW: Do you have a favourite part?

EM: No, I don’t. The movement of the whole thing is amazing. It just changes. I first read it because I wanted to read something of hers. I didn’t know her poetry very well, and I saw this event as an opportunity to get to know her poetry more. When I started to read this poem, I felt like something was rolling underneath it. It felt like it was such a visceral poem, and it was very exciting in itself. When I opened the book, it was just like, whoa. You know? I met her, too. I had lunch with her and her partner in Paris one afternoon, which was fantastic.

SW: What was that like?

EM: She was very warm, and so was her partner. She was just funny and sweet, and it was amazing. At the time, Etel was in her nineties, and my mother was in her nineties, too, when she died. And I don’t mean to compare. There are many things to say about my mother, but she was not like Etel, who was so herself about the things she cared about all her life. There was no waning of intention, whereas I think my mother never had an intention. I know it’s cruel to say, but my mother never picked a direction and went there, and I could see the difference between her and Etel. All these physical things happen to a person as they age, but to my mind, it seems like an intention could be what you need, what you hold onto, and what you do in your life, which informs the end of your life. Etel was bright with what she had done, who she was, and what she was still excited and interested in. She was interested. She didn’t say, ‘Oh, I know your work, I love your work.’ But I felt this and thought that was why I was a welcomed guest.

SW: I’ve been watching many videos of Etel reading in the past few months. Last night, I was sitting in a park with a friend having dinner, and we looked over at this woman. I was like, ‘She looks exactly like Etel Adnan.’ This woman was with her husband. He appeared to have dementia, and she was taking him on a walk, and they had a slab of Kinder Bueno chocolates. They were walking around, and this woman was so sweet – she kept talking to us, sat on the bench next to us, and just looked at us, smiling the whole time.

EM: Incredible. Was she Australian?

SW: No, she was French. What do you think of Paris? Have you been here much?

EM: Yeah, I like Paris. When I’m there, I often think, ‘Oh, I could spend time here.’ But I also feel like it’s one of those cities that are difficult places to live, and people don’t talk enthusiastically about it. I feel like people sneer at it a bit. I was in Brussels recently, and people love Brussels, so many people are moving there. It’s a great place right now.

SW: I’m more of a fan of Paris than Brussels. I don’t know why. Whenever I get to Brussels, I think, ‘Take me back to Paris.’ I’m trying to understand why. But I think Brussels is fun, and maybe it’s more laid back, and people are nicer, maybe?

EM: I think people are going to Brussels because they can live there. Young artists are there, you know? And, for me, that makes a more interesting city. There’s a vibrant art scene. The art scene in Paris could be better. Are you in Paris now?

SW: I’m in Paris, yes, but I have friends who live in Brussels …

[Dog barks in the background.]