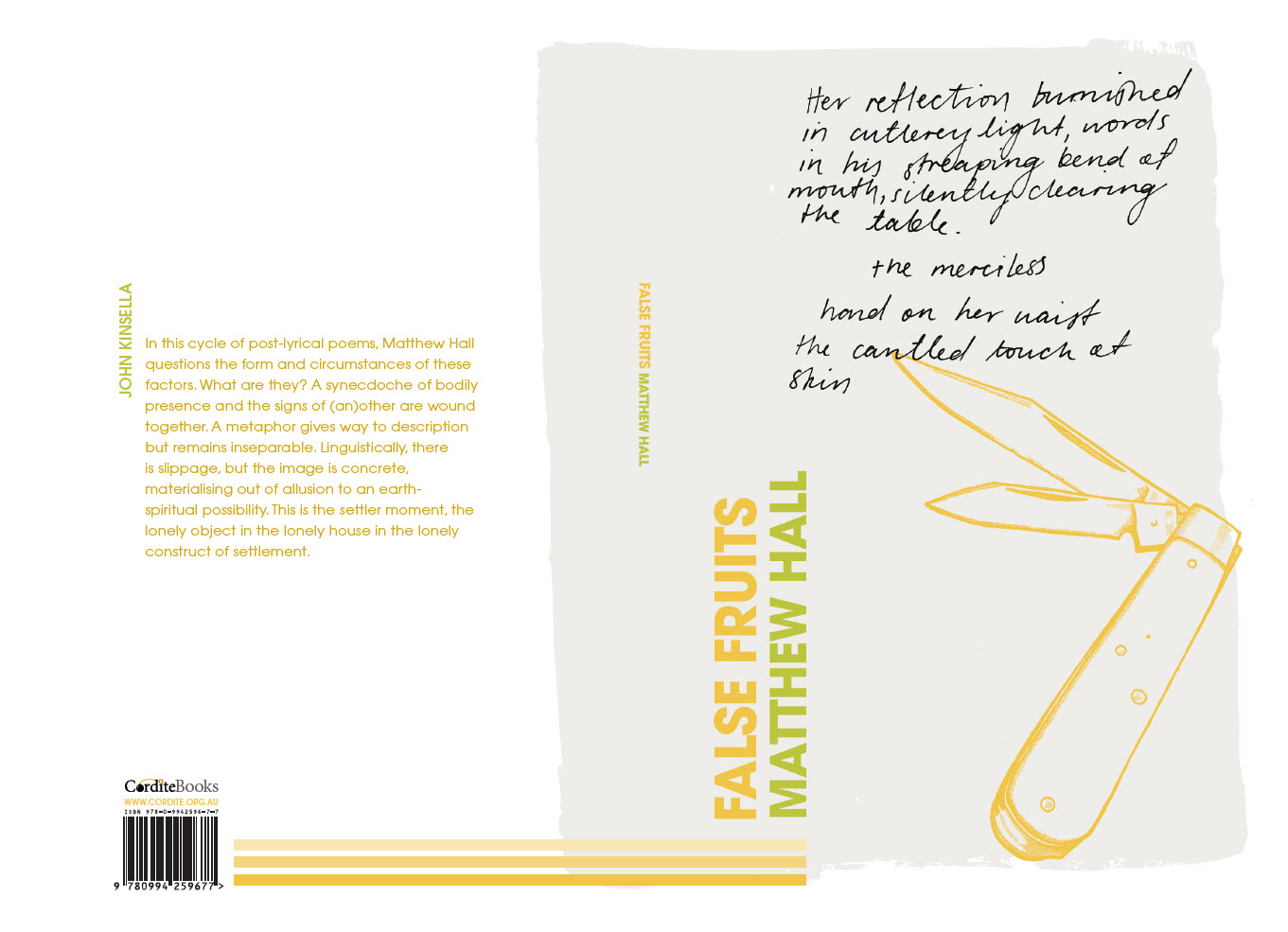

Cover design by Alissa Dinallo, Illustration by Lily Mae Martin

Fruit is the apogee of the pastoral. It’s what the work, the waiting, the ritual and the thanks are for. But the making of fruit is costly and even the ‘natural’ cycle of things will be managed so some factors are privileged over others. In this cycle of post-lyrical poems, Hall questions the form and circumstances of these factors. What are they? In foxlight and in the swell of earth, in the familial connection to place, in the exclusion and recidivism of (be)late(d) presence. What are the rights of creating conditions of fruition?

In tracking presence, we find markers on the trail. They are mythical and totemic; they are every-day and matter-of-fact. They are expected but never prescriptive. As we follow the ley lines, we learn:

‘Her throat is clouded with leaves; underneath the black spruce, bird tracks scrawled through the feathered dust.’

A synecdoche of bodily presence and the signs of (an)other are wound together. A metaphor gives way to description but remains inseparable. Linguistically, there is slippage, but the image is concrete, materialising out of allusion to an earth-spiritual possibility. A ‘want to believe’ because the signs are there to follow. The poem goes from wrapped line to the succinct embodiment of the lyrical urge:

sky swelling the shuttered leap a whittled toy rolling on the stone floor

This is the settler moment, the lonely object in the lonely house in the lonely construct of settlement. It takes the weight of haunting, not only because of its isolation, the space around it, but because it is a caught (photographed, staged, ‘shuttered’) moment. The light interrupted from the available expanse of sky outside that is artificial in its appropriation. This is the invader’s toy as much as the settler’s toy, but it is also part of a quest of reassociation, of belonging because there is a belonging that stretches back through the bird tracks. We have the indigenous and non-indigenous in conversation and tension.

And so we are ended in the bracketing final line: the final cut of this arrangement on the disturbed and dilating field of the page:

The field tussled in the silence of consonant feathers.

Loss of breath in making a sound and harmony. The paradox of the consonant and the softfall of the feather. The feather takes a lot of weight and cannot find its vacuum. It has to be heard and seen and we might add it to our tools of comprehension but never own it.

To encounter and re-encounter is motion. And a motion that is exacting. To return and discover again, continuously, can bring only the satisfaction of knowing you have left, and that things can never be as they were. What do you bring back to a place, an indigenous space you are ancestrally part of, but from which you have separated yourself. Is this ‘return’? And is ‘his’ return an inevitable part of ‘her’ accepting of the field and the field’s accepting of her? Can he be the conduit and she retain her agency, autonomy? Does family mean inclusivity? The poem worries at its own edges. As each section of the book accumulates, our middle-ground lyrical enactments and condensations grow 3 … 4 … 5 … 6 lines bracketed, then the split across stanzas. The chasms. The 5 lines… 4… She struggles with the growing belonging:

‘The cascade of his rapacious grip, her shadows through the cedarn crown.’

She is missing something, something of outside, of other belongings. Of other connections. He tries to draw her to his understanding, his inchoateness. He is struggling with a conviction of understanding, of relationship to land, of the interference of the Western machinery of myth and materiality:

‘Beyond the ravine, a dark world pulses through lapsed cathedrals. inexorable day harrowed leaves rusting in purgation tannins consonant in rivulets descant in the tethered shade

She lives by disconsolate gift, the shrived night, untethered seam, the lassitude of summer.’

The house of the self, the family, the birds who are auguries in the literary construct but birds in the moment. The tension of pastoral presentation of a feeling of belonging strained by the alienation of external experience. The lines are trails but they are curtailed by material reality. The domestic is servitude and joy of presence is also:

the thankless tasks of false fruits

Reverence, labour, rustic performance, curtains and animals and:

‘His embrace and shadow, murmurs a child a child, as she aches into branches.’

The seasons work away and winter yields its ‘last bird’. The cost is high, but the nature of cost is undecided. So the prairies exact their measure, and persistence is a narrative sold to the future. And it is extraction: it is theft, too. A theft that costs the theft of self. The colonial residues that make the ground too furrowed, that we must read through, to follow the consonant feather to its origins, to its stories. The overlays of settlement to be read through and out. The gender entrapment of home and landscape, governance of weather, the emergence of nation (Canada) which costs and costs. There can be no lyric in this most beautifully lyrical lament: the witness is also the victim. And he has invited ‘her’ into his irresolvable paradox of belonging and exclusion.