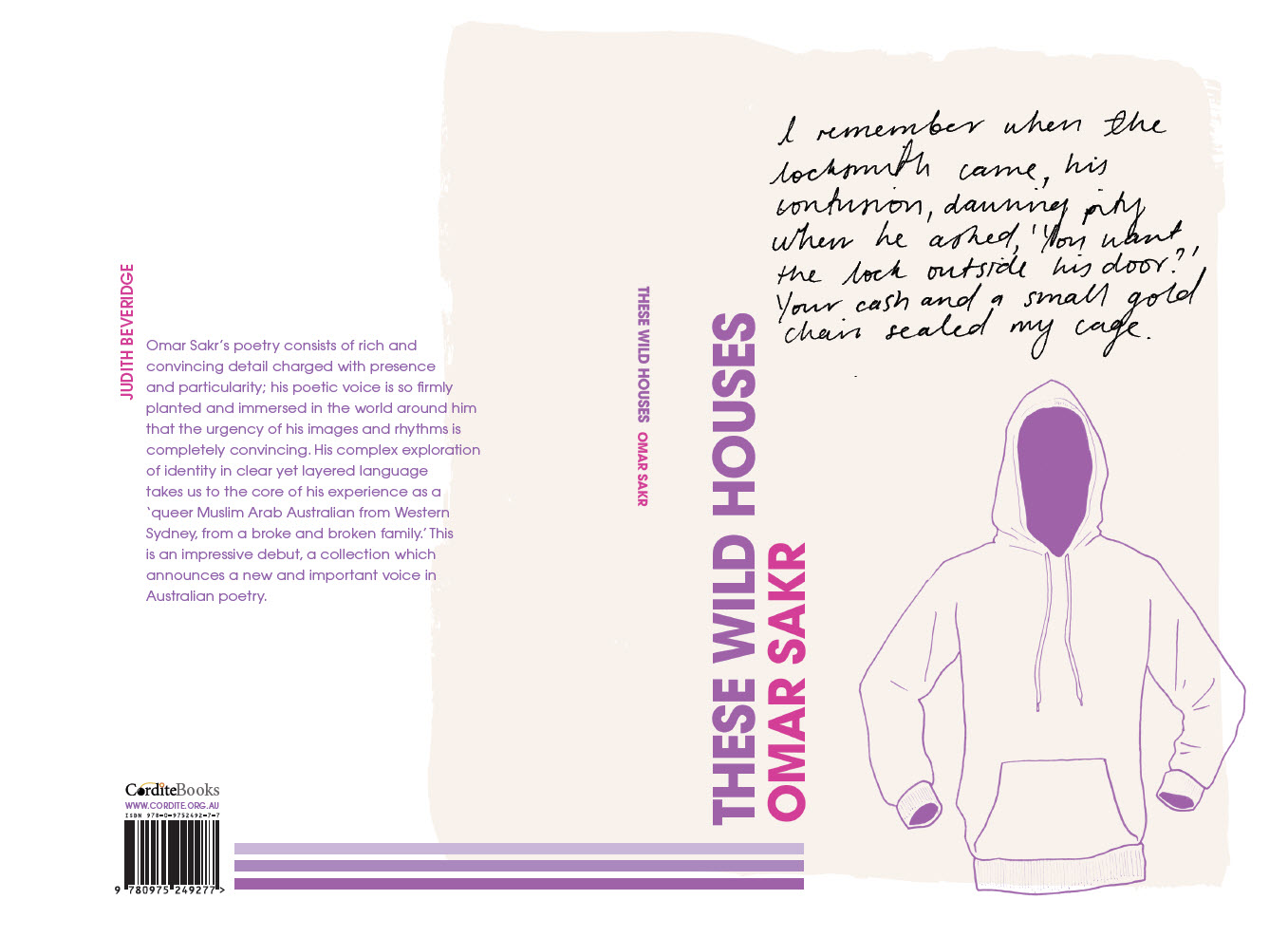

Cover design by Alissa Dinallo, Illustration by Lily Mae Martin

Cover design by Alissa Dinallo, Illustration by Lily Mae Martin

Omar Sakr’s These Wild Houses is a complex exploration of identity, an identity exposed in clear yet layered language, a language that takes us to the core of what he has experienced as a ‘queer Muslim Arab Australian from Western Sydney, from a broke and broken family.’ Given the rarity of Australian poetry written from these particular perspectives, and given that all these labels still carry stigma and disadvantage, you might think that you could guess the tone and content of the poems from these biographical details. You might expect anger, rage, resentment, bitterness, poems that rail against prejudice and injustice, and while these emotions do feature in the work, they are tempered with compassion, warmth, tenderness, understanding and supple perceptions. In the first poem, ‘Door Open’, Sakr welcomes us in to his world: ‘Come inside, let me / warm you with all I am’. And he does warm us with his intimacy of voice, his inclusivity, his emotional diction.

There are many references to houses in the volume, and for Sakr these are important sites: places in which we can come to terms with who we are, places where we learn the stories about ourselves, and among other things, where we can experience displacement, cruelty, neglect. In ‘ghosting the ghetto’ he tells us how in ‘their third floor brick flat, the one tucked into the asphalt folds of Warwick Farm … my grandparents were rebuilding Lebanon’. This beautiful poem with its long-breathed lines and confluence of rhythms explores generational change and the way in which Muslim and Australian worlds collide and intersect: ‘Beirut became Bondi became Liverpool, & the local creek behind the cricket pitch / drank the old rivers, and new names blessed our flesh: Nike, Adidas, Reebok.’ In many poems he delves into complexities and complications that arise from coming from a multi-cultural background. In ‘All My Names’, he says ‘I never knew / what to do with all my names, these silhouettes, of a boy I never was or wanted.’ Throughout the book, houses and rooms are metaphors for states of being; as he says in the final poem, ‘A house should, above all, be still.’

What strikes me especially in these poems is the way in which Sakr grounds his work so indelibly in the body. He knows thoroughly that the body is the primary house, the one in which our identities are irrevocably caught: in the skin, under the skin, in the heart.

In many instances this knowledge is rhapsodically transformed, as in these lines from ‘What the Landlord Owns’:

… unfamiliar language is no barrier when you dwell on the borders of domesticity, when the soft hands of the sun sculpt the sloping muscles of a man like sand as he mows the lawn, and hair muzzles his face

Sakr’s poetry consists of rich and convincing detail charged with presence and particularity; his poetic voice is so firmly planted and immersed in the world around him that the urgency of his images and rhythms is completely convincing. Sakr never summarises or straitjackets the emotions; instead he allows the tonal range of his voice to surface through layers of astutely organised rhythms and imagery.

These Wild Houses is an impressive debut, a collection which announces a new and important voice in Australian poetry.