Figure 5: Holey Dollar and dump, first distinct coinage of New South Wales, 1813, State Library of NSW

In a comparable if slightly different vein, Australian poetry before 1819 can also be understood as essentially convict poetry. There were of course poems, like that by Darwin, being written about Australia – or, more precisely, about the landscape, flora and fauna of the colony – by people who had never been to nor even seen what they were writing about. Of poets actually residing in New South Wales, the principal one, up until 1819, was Michael Robinson, who was Macquarie’s designated court poet, and who had been transported back in 1798 for extortion by means of a defamatory poem – a paper crime not so distant from the forgeries of other convict artists. Between 1810 and 1821, Robinson duly churned out a sequence of odes celebrating royal birthdays and official events. Prior to Macquarie taking power in 1810, poetry had appeared regularly in the Sydney Gazette, but it had been published anonymously and received no official recognition. From 1810, most of the poetry it published was by Robinson and appeared above his signature. The libellous or unauthorised manuscript ‘pipes’ that appeared throughout this period were necessarily anonymous – convict literature by definition, even if sometimes written by officers.

In the situation prevailing in the penal colony that was New South Wales in 1819, we are then confronted by the dominance of a certain regime of images, at once commercial and legal – in a word, imperial – emblematised by the dominance of the Wedgwood/Great Seal nexus. We are confronted by a literally material network of images: the clays of the land and the imported metals. We have the preponderantly circular shapes of the coinage, medallions and seals. And we have their viral mobility and plasticity, literally stamped with a crown and circulating everywhere.

Field’s First Fruits of 1819 was then not just the first book of poetry. It was also the first clear and definitive work of non-convict poetry in the colony. Here, the phenomenon of romantic authorship is decisive. When Field titled the first poem in his little book ‘Botany-Bay Flowers,’ for instance, that name in 1819 signified a rupture and a return. It was a rupture with the fact of the penal colony and what would perhaps not-quite-yet be able to be poetically named its fleurs du mal, its criminal population. It was a return to the inspiration for Cook’s name itself: the lush profusion of extraordinary natural flora that so excited Banks and Solander at the site. The title said no to the particular circumstances of settlement while saying yes to the untrammelled natural profusion of a truly strange and estranging place. While it may well have been impossible for Field’s intervention entirely to expunge the residues of criminality from Botany Bay, it was surely just as impossible that the active presence of the original inhabitants be simply ignored or repressed. Field’s self-set poetic task was complex. To become a modern nation, Australia had to be constituted as neither natural nor criminal. And it had simultaneously to avoid the threat of revolution as exemplified by America and France.

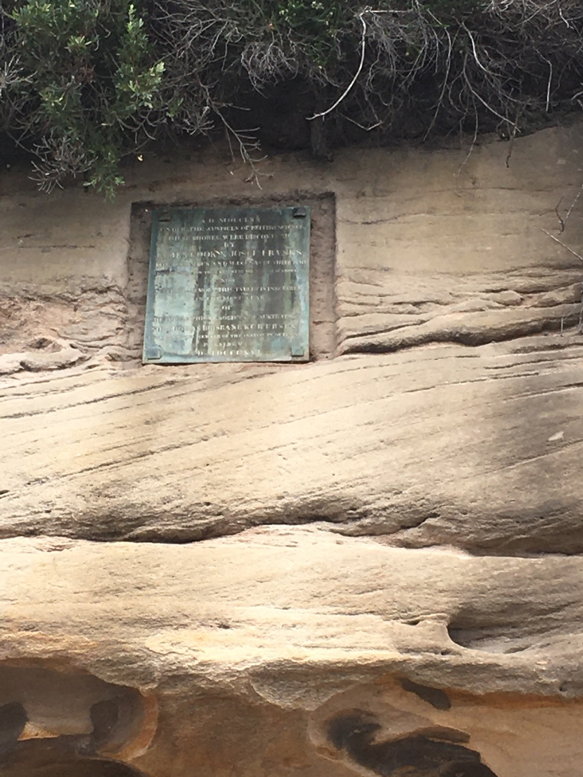

On Wednesday 20 March 1822, Field – who fully orchestrated the event – led the new Governor Thomas Brisbane and members of the Philosophical Society of Australasia (a society that he had himself founded) down to the rocks at the south head of Botany Bay, where they enjoyed a meal before a brass tablet authored by the Society (that is to say, by Field) was soldered to the rocks, and the assembled luminaries drank a toast to Joseph Banks and James Cook. The tablet, shown in Figure 6, commemorated the ‘discovery’ of ‘these shores’ by Cook and Banks some fifty years prior: ‘this spot once saw them ardent in the pursuit of knowledge.’1 When Field reissued his book First Fruits the following year, it contained four new poems, including two sonnets, themselves clearly paired and emblematic, which had been written expressly to accompany the tablet. Field’s tablet/sonnet assemblage was, like the Wedgwood-Darwin medallion/poem assemblage, a kind of multimedia artwork that coupled a site-specific installation with the placelessness of print poetry. And the verbal images presented by the sonnets refer quite clearly to the visual images on the Wedgwood Medal and the Great Seal. Those visual images, however, in being taken up in the poems, were handled in such a way as to transform their scope and operations.

Figure 6: Field’s tablet, Inscription Point, Kurnell, 2021.

The two sonnets in Field’s second edition are highly reflexive poems about the real act of memorialisation that they describe and accompany. The first sonnet is a retrospective reimagining of the act of conquest itself, deploying such oppositions as gun v. spear, white v. black, wood v. brass; the second is a time-travel fantasia imagining what Banks and Cook might feel were they to be posthumously present at the act of memorialisation orchestrated in 1822 by Field.

- Ford & Clemens, Barron Field, pp. 135-136. ↩