Figure 1: [Sydney Cove Medallion], 1789 (original issue)/ Josiah Wedgwood, State Library of NSW.

While working on the clay, Wedgwood invited his friend and fellow Lunar Society member Erasmus Darwin to write a poem to accompany it. The poem and the medallion might be thought of as two distributed elements of a mixed-media artwork, establishing a close aesthetic relationship between poetic language on the one hand and, on the other, an artefact made, quite literally, from Australian soil – a relationship that would be important later for Barron Field. In Darwin’s poem, titled ‘Visit of Hope to Sydney-Cove, near Botany-Bay,’ Hope prophesies a great future for the fledgling colony, notably mentioning a ‘proud arch’ which, ‘Colossus-like,’ will ‘bestride / Yon glittering streams.’1 Notably absent from the poem was any mention of the enforced nature of the labour that was to build this settlement: you wouldn’t know it was a penal colony from Darwin’s poem. Also absent was any mention of the Aboriginal people whose cultural use of this clay had first called it to Banks’s attention.

Commentators have often noted these two glaring absences in Darwin’s poem: no convicts, no Aboriginal people. Less commented has been a point that we want to underscore, which comes in the poem’s final lines:

Then ceas’d the nymph – tumultuous echoes roar, And JOY’s loud voice was heard from shore to shore – Her graceful steps descending press’d the plain, And PEACE, and ART, and LABOUR, join’d her train.2

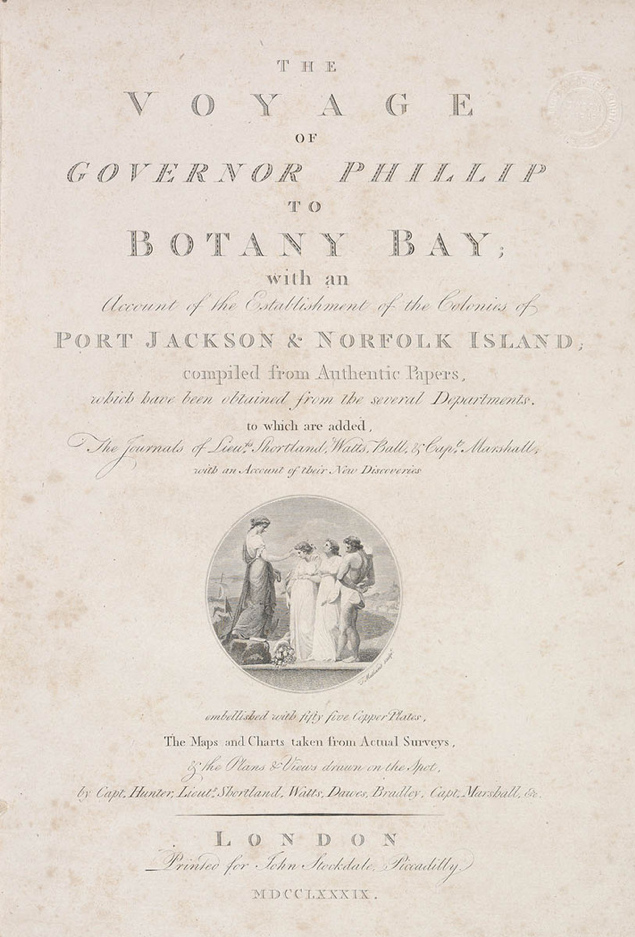

With these lines, Darwin figures his own poem’s making, and the making also of the medallion to which the poem formed a verbal pendant. Hope’s graceful steps tread in the poetic feet of Darwin’s iambic lines; the plain they press is formed in part of the clay that has received the impression of Wedgwood’s artifice. As Phillip would write to Banks, after Banks had sent him a medallion: ‘Wedgwood has showed the world that our Welsh clay is capable of receiving an Eligant impression.’3 This semantic matrix involving press and impression – centred around the stamping of the earthy material with an allegorical narrative designed to justify its seizure – was further extended to including the printing press when an engraving of the medallion appeared on the title page of The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, published in 1789 – shown in Figure 2 – with Darwin’s poem also being printed in the book a few pages on.

Figure 2: Title Page of The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, 1789, State Library of NSW.

Writing and printing – and, in particular, writing and printing poetry – were then already connected by 1789 through multiple links, some quite literal and some more metaphoric, to the imposition or impressing of British narratives of order and progress on Australian soil at a continental level, from ‘shore to shore.’4

We’ve dwelt at some length on the medallion in order to bring out this point, which will be important for Field’s revisionary poetics, his modernisation of colonial art and society. We need now to turn to the next part of our story, in which the medallion’s allegorical design was reworked as the device on the official Great Seal of New South Wales, which was sent out to the colony on the Third Fleet.

The use of seals was central to European practices and ceremonial forms of governance. As Mary E. Hazard notes, invoking an historical example that was moreover of extreme pertinence to Field himself:

The Great Seal was the most important of all seals because it certified all important state documents. It was kept by the lord chancellor, and its importance in defining and dignifying his office explains Cardinal Wolsey’s historic reluctance to surrender it when he was toppling from power, as is dramatised in Henry VIII by Shakespeare and Fletcher (3.2.228-349).5

The Great Seal is required to appear on all official state documents that demand the monarch’s direct authorisation: for Commissions of the Peace and Ratification of Treaties, for Royal Proclamations and Parliamentary Writs, and so on.6 The monarch’s Great Seal was the authorising model for its many subordinates and simulacra. As the British Empire expanded throughout the eighteenth century, new seals were required for new colonies and dependencies across the globe, and the production of official seals was accordingly considered a matter of priority in the founding and dispensing of colonial law.

- Arthur Phillip, The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay (London: John Stockdale, 1789), p. v. ↩

- Voyage of Governor Phillip, p. v. ↩

- Arthur Phillip to Joseph Banks, 26 July 1789, no. 0003, series 37.12, Banks Papers, SLNSW. ↩

- On this point, see also Elliot Patsoura, ‘Transplanting the future: Erasmus Darwin and the onto-poetics of climate,’ Eighteenth-Century Life (forthcoming). ↩

- M.E. Hazard, Elizabethan Silent Language (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), p. 126. ↩

- Online, 7 November 2023 ↩