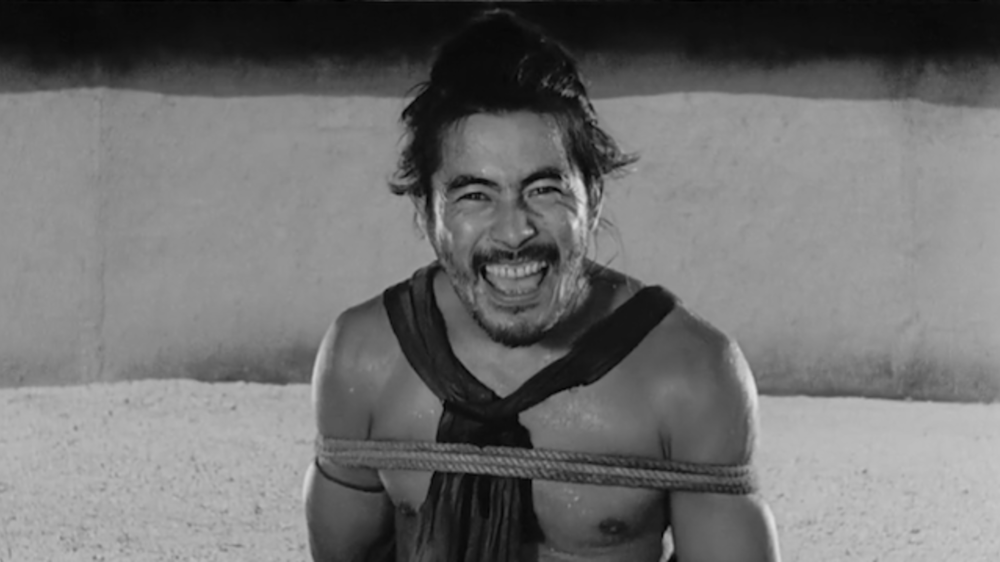

The Bandit

And what of all the out takes like a bowl of pistachio husks? The bandit sits up in a forest clearing near Rashomon. ‘What do I do now?’

These lines are from a second poem of mine about the image of the actor Toshiro Mifune in the Akira Kurosawa film Rashomon (1950), a follow-up to my poem ‘The Bandit Without Mifune’, which refers to an autonomous image of the bandit character waking in the oil of the celluloid – a much better line than those above, I know. In the first poem, the superior poem, the bandit (who is in a black and white film) asks, What shall I do with my silver limbs? The whole image from the first, published poem goes like this:

I have woken disembodied in the still black river of an unplayed film. It is frightening to wake In the oil.

Toshiro Mifune as The Bandit in Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon.

The second poem is unpublished – it is in fact unfinished. I think this is because there doesn’t need to be a second poem. It is just me returning to the same problem for myself. In the second poem, there are other signs of weakening: the oil has become a forest clearing, as it appears in the movie. Already the poetry is coming unstuck from the original problem I was pursuing. In the first and published poem, this character appears startled and confronted by his own sudden consciousness, independent of the actor, the director, and any outside power or intermediary other than the image itself. The character is confronted by a problem of something that, across several of my poems about films, I came to call the exoskeleton.

This essay has become an effort towards comprehending some of the persistent themes in my poetry so that they may evolve, or be used more completely, instead of being always rediscovered like forgotten dreams. It could be assumed that the act of publication, as with ‘The Bandit Without Mifune‘, would do that for me, would affect a completion. I wish it had worked that way. I am trying to understand the fact that it did not. If the image was not psychically resolved by it being used in a poem – a finished poem that I was satisfied with enough to publish – then part of my motivation for writing poems is now compromised. That’s what I understood my writing to be about – resolving the images. Tending images in a way that comprehended them on a subconscious level. Instead, preparing for this essay has revealed that some images have remained unresolved. This is confusing, as I don’t understand myself to have another method for this psychic work other than poetry.

Explanation in the form of essay is something I always associated with university, and with my work being evaluated by busy persons who were also evaluating many others’ work. Because of that situation, my past essays were aimed at helping those readers, not me. However, this essay is aimed at helping me to search through the recurring images in a way that might resolve or define them more in my own mind, and it is able to approach this because it is done in the company of poetry readers.

On the hardcopy draft of that second, weaker Mifune poem, which I am looking at now, much of it is crossed out. In my usual process I write longhand, then transcribe to the computer, then print it out, then annotate on the paper, then transcribe the changes, and then print it out again. This can continue for years. In fact, now that I think of it, it usually continues for years. I would like it to resolve far more quickly. Maybe if I move more quickly, the images will not ‘throw so many spores’ and spring up in additional places.

Two of the crossed-out stanzas deal with the idea of a spirit independent of the body, not for the character of the bandit in this film, but for myself. They read:

When I turn the page and there is illegible writing ... I prepare myself for great interpretations.

I write poetry like it is too hot – too hot to touch, too hot to think about. I write in the mornings to fit it in before work. I write quickly and am relieved to have lodged something, to have paid respect in this way. It’s like the poem is votive.

But I also write poetry and then forget it completely. I start again all the time, and then later discover drafts I had forgotten about. I also write all the time, which I am so thankful to now have as a habit, and this has come from my job as a writing teacher at university, where I help Business students. This is not as tangential or separate as it sounds, as having to help people who are not natural writers really strips things back. I am a much better editor for it, and better, I think, than if I would have just stayed in poetry, in creative writing, where people can be stubborn and feel hurt from intervention on work they’ve explicitly asked for intervention on. I was like that myself. But in the Business School I formed trust with students by asking for a bad draft – I called it a crap draft: Just give me any crap draft, it’s fine! – so we’d have an object to work on. This can be likened, in some ways, to shooting a lot of interview footage for a documentary and then deciding what the core scenes are, and then seeing what new scenes need to be filmed to fill out the story. But in the Business School we kept it way more rudimentary. We didn’t use documentary film as the metaphor. Instead, we used the metaphor of the table.

Pingback: Catching up a bit… | Poems about Tarkovsky films