Featuring poetry by Lillo Way, Jacqueline Haskins, Jeremiah O’Hagan, Marie

Hartung, Robert Hoffman, Leone Mikele and David Wagoner.

American poetry has never been more diverse in form, content, and intention than it is today. All imaginable styles and mannerisms are being made use of and show up in literary journals, and there are more of those outlets than ever before, not counting the numerous new online magazines.

Most of the turmoil is taking place in what used to be the no-man’s-land between poetry and prose, with most of the partisans fighting it out in the muddy shell-holes by the light of short-lived parachute flares, neither side being able to identify the other in the general free-for-all.

There are no literary dictators presiding over this, no commanders of taste, no truly authoritative figures making the rules. If critics think up new rules for the art or craft of poetry, dozens of overjoyed poets try to violate them immediately and may even form a new School with a half-dozen members.

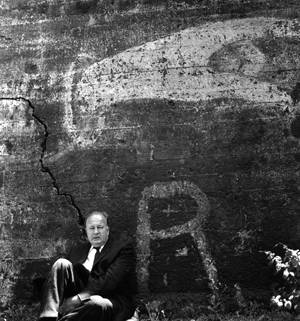

The same is true of poetry being written in the American Northwest, but there is, I think, a notable difference. Poets in the northwest part of this country once were a rare breed, strictly local and unknown. They scarcely existed till the arrival of Theodore Roethke who, as a kind of Midwestern savage, had been winning prizes in the loftier literary East, began teaching at the University of Washington in Seattle in 1947. His English Department chairman at that time told him, ‘Ted, it’s all yours. There isn’t another poet for 500 miles in any direction who’s publishing in national magazines.’

Some of Roethke’s students in that first year and during the next six were James Wright, Richard Hugo, Carolyn Kizer, Tess Gallagher and myself. William Stafford wasn’t a student of Roethke, but became a close observer. All six of us became teachers of poetry ourselves – Wright in Minnesota and New York, Hugo in Montana, Kizer in several universities in the South, Gallagher in upper New York State, Stafford in Oregon, and myself in Roethke’s position after his death in 1963. All of us became, in our turn, winners of national prizes like him, some more than once. And all of us followed in our work and teaching one of his basic principles of the craft: the effort to unify sound, rhythm, and meaning, to treat them as equally important insofar as it was possible in any and every poem.

It’s not surprising that living in the Pacific Northwest of America has an unusual effect on writers. Its landscape is extremely dramatic. There are more climate zones clustered here than in any other place in the country, with the possible exception of Yosemite Valley in California. On the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, in the last virgin rain forest in North America, we have the largest weight of living matter per square foot on Earth. You can drive from the sea to the alps in 45 minutes; see desert tortoises crossing interstate highways; watch salmon making their stony nests on your way to work. There are several more volcanoes that haven’t been heard from lately with unpredictable ideas about the future. And there are innumerable places where you can get lost in the woods without half trying.

The editor of this journal asked me for an essay, and I told him I didn’t write any if I could help it. You can probably already tell why. Then he suggested I act as ‘curator’ for a group of six current Pacific Northwest poets, in addition to myself, in a kind of small exhibition for Australian readers.

I agreed, the results follow on the next pages.

All of the poets included in this chapbook – including Lillo Way, Jacqueline Haskins, Jeremiah O’Hagan, Marie Hartung, Robert Hoffman, Leone Mikele – have recently been or currently still are students of mine, either at Richard Hugo House, the main center for literary activity of all kinds in Seattle, or at the Northwest Institute of Literary Arts, the low-residency Master of Fine Arts program based on Whidbey Island in Puget Sound.