Song in the Grass by Kate Fagan

Song in the Grass by Kate Fagan

Giramondo, 2024

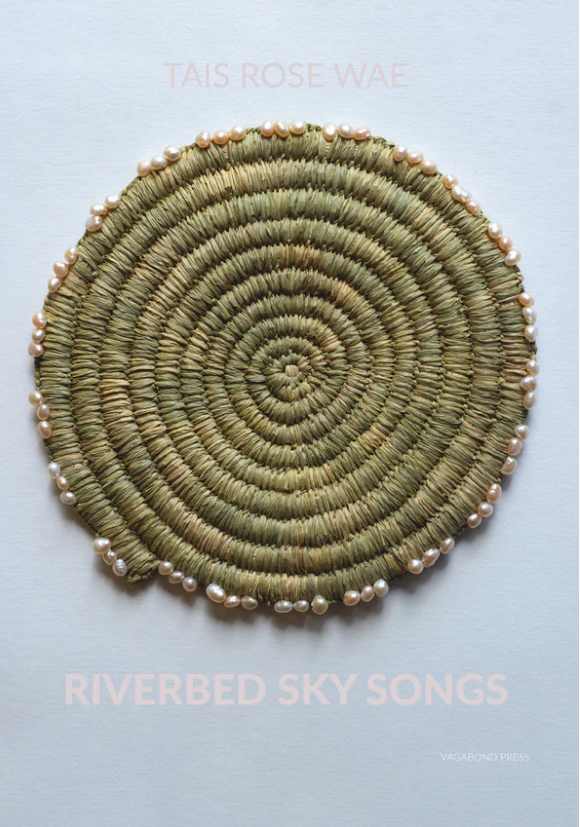

Riverbed Sky Songs by Tais Rose Wae

Vagabond Press, 2023

Both Kate Fagan’s Song in the Grass (Giramondo, 2024) and Tais Rose Wae’s Riverbed Sky Songs (Vagabond Press, 2023) take motherhood and song as a means to meditate more broadly on interconnectedness, embodiment, and the possibilities of poetic language. Most of the poetry in Song in the Grass was written on Dharug and Gundungurra Country while Riverbed Sky Songs was written on Bundjalung Country. Song in the Grass is Fagan’s third major collection following First Light (Giramondo, 2012) and The Long Moment (Salt, 2002). While Fagan’s First Light was shortlisted for the Kenneth Slessor NSW Premier’s Literary Award in 2013, Wae’s debut collection, Riverbed Sky Songs, won it in 2024. The making of poetry for both is part of a multidisciplinary creative practice; Fagan is an internationally renowned folk singer and musician, while Wae is a talented weaver. At the heart of both their collections is a contemplation of how poetry is not separate from but rather part of a holistic understanding of being in the world, and how it can convey the experiences of embodiment and relation. Joy Harjo points out that “[p]oetry is the closest step to beyond language, beyond the words. You absolutely need the words, but you employ language in poetry in a way that’s kinetic, spiritual, and sensual.” For both Fagan and Wae, situated creative practice is always accompanied by an awareness of stories of place – the shorter period of colonialism and its violences, and the vaster one of First Nations care and respect of Country.

The fingerprints in shades of green on the cover of Fagan’s Song in the Grass are a reminder of the hands involved in the making and the traces left behind by sentient forms. In ‘Good Nature,’ a poem addressed to her partner, fellow poet Peter Minter, she writes of wanting to “offer you a pocket of songs, a book or two, names for all the birds” (58). Accordingly, this collection opens with ‘one year one garden,’ which catalogues all the bird species that have traversed their Blue Mountains garden in a year (3). It is a list poem, a favourite form of Fagan’s, yet it refuses the linear movement down the page that is common to the list poem. Instead, she turns to the prose poem which, instead, clusters the birds in one place without punctuation, that is, fixing them adjacent but apart by grammar. ‘one year one garden’ provides insight into how the volume investigates what it might mean to gather poetry and beings together over time, all the while critiquing the settler colonial impulse to inscribe a possessive knowledge over the more-than-human.

For Fagan, collections “share a kind of certainty: we survived, felt purpose, rekindled our love and loss among featureless days” (45). At the same time, she suggests that her own collection is open-ended and provisional in the use of the pronoun ‘we.’ This ‘we’ is both those within the present and of the past. A collection is a house, but, as Fagan notes in ‘Border House (Notes to a Bird),’ houses themselves may be “repurposed by generations” (5). A house has “an open architecture of memory” even as it is itself “an act of minding” (5). A house may collect birds “as birds collect time” (5). Her poem concludes, “[a] house is an ecology of sensing” (5). This attention to a material ecology is what makes Fagan’s writing so remarkable, whether it be directed to a bird making a nest or the poet making a poem and then connecting it to other poems.

As a figurative house, Song in the Grass has many rooms. Its first section, ‘Notes to a Bird,’ reflects on what it means to have dwelled in one place for many years, tracking the learning curve to navigate a mountain valley’s rhythms and hazards. This includes the loss of chickens and awareness of the vulnerability of wildlife to cat, car, or rat trap. We get a sense of the poet as mother, who raises two babies that, in their turn, begin to navigate the environment. While daughter Ruby considers a “great sequoia” in ‘Pinecones,’ she clutches its seeds and declares, “If I plant these / we can come back and see / when I am older than this garden” (4). In contrast, the speaker reflects on “geologic time,” the “basalt peaks” capped by gums and the “parent century” from which the trees have come (4). Another poem, ‘Elegy for a Felled Eucalypt,’ mourns the loss of a many-storied, ancient tree and notes the many lives accommodated by its canopy or base. This includes the poet and her daughter, the poet saying, “I am sorry and sorry again” and feeling the need of words “to sing you away” (17). Fagan’s poem offers no consolation, only sitting with “just your shape / remembered, loved and bare” (18).

A number of poems in Song in the Grass are part of collaborations with musicians. ‘Our Mother’s Heart’ and ‘Evening Devotional’ have a spiritual orientation (19-29; 22-23). Written in the backdrop of bushfires, the former is a praise poem “for what endures” even as we experience “burning days” and “muddy lakes” (19; 19; 20). Life is still found amid “silent ash” or in the voices “on the mountainside,” with rain itself “an eternal art” and the moon a reminder of cosmic labouring (19; 20; 20). Time here is not that of colonial teleology but vaster, with every element of an ecology carrying what came before into the present. A further collaboration with composers Nicholas Ng and Waldo Fabian Garrido is a calendar, or “[e]arth [l]ist,” populated by birds, with Fagan saying in a later poem again, “My clock would be mountain-shaped with a bird at every hour and feathers for hands” (‘Bird Calendar (Earth List),’ 24; ‘Thinking with Things,’ 44).

The titular ‘Song in the Grass’ becomes an elegy for Irish writer Dermot Healy in its antipodal shifts. It is followed by a sequence of shorter poems or ‘letters’ to writers that build a community and often signal a particular shared moment. This includes a poem to Yankunytjatjara writer Ali Cobby Eckermann of their time on Ohlone land, California, their maternal love, “a blazing harbour” (41). It contains an elegy for poet Martin Harrison, who taught many how to listen to the pause in language and world. “Perhaps your last river / was copper brown and green, / a long wing carrying you home,” Fagan writes, again continuing the bird and water leitmotif (51). Even ‘Thinking with Things,’ dedicated to poet Pam Brown, mulls over the sound of cockatoos and apple trees “knotting to fractal profusion” (43). It celebrates Brown’s “continuous rediscovery” and her acute irony, as signalled in the cemetery’s graffiti, “DO NOT FROLIC” (44).

The transcultural chords of ‘Song in the Grass’ are continued in the ‘Portable Craft’ section. A journey between Australia and China is explored through the pebble, which calls up the pearl, the seed, the bead, the lodestone, and the inkstone. “Each particle is moving in relation,” she suggests, “in metaphor” (63). A serial poem addressed to the late American poet and friend, Lyn Hejinian, sees the poem morph speculatively over time: “A poem is a machine made of birds […] Branches move in and out of frame. The poem transforms into a creek” (65). There is an additional playfulness, Fagan notes how swallowing a word leads to a sinkhole. She concludes, “Next time I see a word I’ll think twice about eating it” (66).

The final section contemplates the poet’s role as collector or gatherer. Fagan looks back to nineteenth-century naturalist Louisa Atkinson, her interest in botany, her home in Fernhurst to the west of Sydney, and her role as a young mother, all shadowing Fagan’s own to some degree. Each plant mentioned in ‘Death Among Them’ is “painted, drawn or described by Atkinson in her diaries, sketches, journalism and literary works” (99). As Fagan notes, colonial exercises of classification were “volatile projects,” part of the process of elimination of Aboriginal knowledges (99). A following poem, ‘Future Green’ speaks of lichens “that form / their own story” and “[s]pore archives” that lie “in grass, / sovereign green, / hard to classify” (80).

“Bodies learn to inhabit a law of doubles,” Fagan writes in ‘Effie Wakes at Midnight,’ although this applies to words in her collection, as their repetition creates subtle sound-threads of continuity (79). In an interview for Australian Book Review, she speaks of a sculptural approach to redrafting poems, seeking a balance of sonics and space. Song in the Grass is a singular song, an extended poetic sequence that is “a space of feeling and observation over months, even years” (ABR, 2024). Accordingly, it “offers a ‘home’” to which the poet can “return continually” (ABR, 2024). Its final poem, ‘The Midnight Charter,’ is a documentary poem, more specifically an extended inventory or list. Tapped into a mobile phone over five years, it echoes words from previous poems as it navigates the complex histories and paradoxes of the contemporary world, its mourning and its joy. A charter is the written grant from the sovereign of a country. Here, it is the sovereignty of Country. Midnight is both a space of darkness as well as the liminal transition from one day to the next. The poem concludes with almost a mantra, “I wrote awake awake awake awake awake” (92). This alertness is what Song in the Grass imparts: even at the end of day, or against the one-minute-to-midnight end of days, it calls to its readers to attend to our interconnected lives, to intergenerational care, and to being alive to the deep ecologies we find our home in.