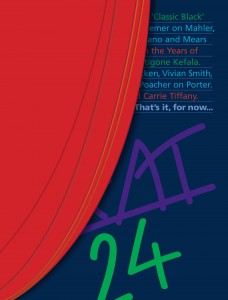

HEAT 24: That’s it, for now… edited by Ivor Indyk

HEAT 24: That’s it, for now… edited by Ivor Indyk

Giramondo Publishing, 2010

This issue of HEAT being named as the magazine’s last could indicate two separate things. One is the opportunity that arises from this; with each ending a new beginning could take place. The other is that the magazine might not be ending. In his editorial, Ivor Indyk cleverly opens with “Though there is always the possibility of a return, this will likely be the last issue of HEAT magazine in print form.” So we might endure a hiatus of feeling the sheer weight of each issue in our hands. Or we might have to convert to reading it online (an option with which Indyk seems quietly animated). Or we might have to say goodbye to the publication altogether. Whichever the outcome, this is somewhat monumental in the scope of Australia’s literary landscape, especially for poetry. Few high quality literary magazines have such a high percentage of poems per issue. I, and many out there like me, will miss that. But Indyk doesn’t play the over-romanticised gimmick card a reader like me might benefit from; this final issue has been produced just like any other issue of the magazine.

I suppose I was looking for a mood. Something that maybe celebrated loss; something nostalgic and dreamy. The first two poets suited half of that craving. Robert Gray’s exquisite ‘Flying Foxes’ concludes with:

but when I look out

at the night, I am offered

otherwise only

the chalk-white, chaste

and lacklustre moon.

After Gray gently rolls out his description of bats and their world, he leaves us with this imagery, which can only be called heartbreaking. Worthy of mentioning here is that at three and a half pages, the poem reminds us we will also miss the long poem form, which has very little visibility in most of our literary publications.

Following on from Gray are two poems by Vivian Smith, one of which ends with the word “ashes”. One might think, from the title and subject of the poem ‘Childless’, that Pip Smith could carry on this atmosphere of melancholic reflection, but the style, the unfixed form of the villanelle, the phrasing of such lines as “You have pig iron shoulders”, is like a spark. It lifted me from the calm shadow in which I was reading and had me smiling, rereading two and three times, feeling celebrative, however sad. So at one-fifth of my way through, HEAT 24 had fed my hunger, and ‘Childless’ had been a long cool glass of water to my water-parched thirst. After my ideal had been realised I was quite happy to settle into the eclectic nature of what has by and large been HEAT for almost fifteen years.

It’s often thrilling to read poetry in translation; as if one was handed a present simply because it is good to give. Thank you, Peter Boyle, for bringing us new writing from the Cuban voice of José Kozer in ‘Three Poems’, all subtitled ‘Anima’. Kozer’s voice is distinctive and challenging, and ultimately philosophical. In one poem, he writes, “I thoroughly chew the fish”; in another, “Everything lies in wait ready to leap out”; and in the last poem, “The ant, a portion of God.” His form is experimental and his subject matter is universal. This is one of the highlights in HEAT 24.

π.o’s ode ‘To Granny Smith’ is delightful, full of energy and filled with a myriad of trivia that suddenly and skilfully culminates in great appreciation for Granny Smith apples. Did you know that

Sunlight is dazzling in its intensity.

A caterpillar has got over 2 ½ thousand muscles.

You can tell when a wasp in a bottle, is angry.

These things are good to know, just as gratitude is good to bestow.

Antigone Kefala’s ‘The Neighbour’ is so simple and so touching, and intuitively spare. Her poems are followed by Amanda Simons’ interview with Kefala, who is as feisty as ever. Kefala talks about writing:

So it is continuous. Like with music. If you give up music for a while, you can’t actually play well. Your fingers are no longer as good as they were. You have to have the exercise.

Poems like ‘The Neighbour’ make poetry enthusiasts thankful she continues to exercise her craft.

Patrick Jones stuns with ‘Food Forest’ and ‘A Sonnet for Zephyr’, with a form of an acrostic, where the randomness of the indented lines form the centrally placed phrases of “Forage Rationalism” and “Harrier Parents”, respectively. As the not-so-subliminal themes suggest, Jones is working with ecopoetics. His poems are a visual mess of jagged edges and variant rising and falling letters. He is aerating his poem, creating a poem as forest and a forest as a poem. There is rebellion on a conceptual level, which can be the fun in ecopoetics. But for me the sign of a truly good ecopoem is one that can stand alone, without the devices affording credit only to the form, and be a truly good poem. Jones gets more than an E for effort here; he is exemplary.

This cherished final issue of HEAT finishes with an essay on Peter Porter by Jeffrey Poacher, where Poacher uncovers place and death in the poetry of the late Porter, questioning whether or not Porter longed for death (even while rejoicing in his cats). It leaves me, once again, with that mood: that one which can only be indicative of something nostalgic and dreamy, something like a celebration of loss. It is a perfect ending for the issue that is “likely to be the final issue of HEAT in print”, so let us not say goodbye, but rather thank you.

Heather Taylor Johnson holds a PhD in Creative Writing and is a poetry editor of Wet Ink.