In the Museum of Creation by Frank Russo

Five Islands Press, 2015

‘…Poetry … puts the whole world out of whack’ according to MTC Cronin in her latest collection The Law of Poetry (2015) echoing the 1930s structuralist definition of poetry as ‘language made strange’.

I think the first poem in a first collection should carry some whack – should both seduce and disturb a reader. And so it is with ‘The Archivist’ at the beginning of In the Museum of Creativity: there are strange and confronting images and phrases which tease partly by problematising what and how we understand language and poetry. So the place (suggestive of a museum, a collection of poems, a gallery of art) ‘shaped like an upturned megaphone’ is ‘A library of sorts. A repository … A beacon, a receptacle, a grave.’ It both collects and signifies but is also a (deathly) memorial. Russo then gives us some textual ‘fragments’ – words of memory and exotic impression, judicious analysis and advertorial insistence, then an encompassing perspective on communication (like the ending of Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See). But then the ‘I’ (poet, pilgrim, searcher after meaning and reassurance) is told these texts ‘…’re not here to be listened to. / They’re a record for all eternity…’ These texts don’t need an audience, their preserved existence is sufficient. Does this mark celebration or bafflement?

One prominent thread of the volume seems to be ekphrasis: an interrogation of objects/art/poetry almost as a meditation on or search for icons for the modern world. For example ‘Through the Ishtar Gate’ advocates for the Virtual Museum of Iraq and its instantiation of a ‘virtual eternity’ – some thing for our brave new world to believe in. The poem is clever for its evocation of the scepticism new technology brings to ancient truths and substances: ‘Here [on the plane] there is no Persia or Asia Minor – / only the below is ancient.’ Present reality determines and recreates (or denies) the past, so ‘Each time I lift the window shade / to glimpse the Hanging Gardens / the Italian couple’s baby in the aisle behind me screams.’ All the same, the poet is disingenuous in marvelling at the human/political impulse to ‘relocate an ancient wonder’ when it’s been done for centuries and indeed, is being done in his poems.

And yet some of the best poems in Russo’s collection have little to do with museums – when he has freed himself from the role of teacher/tour-guide and the burden of needing to make a case for cultural gravitas or iconic significance.

For example ‘The Parachutists, 1943’, a multi-layered historical anecdote juxtaposing the arrival of American parachutists with a local villagers’ evacuation to a cave (carrying their patron saint) evokes both the many possible uses of the discarded fabric (eg. ‘for collecting olives … a shirt for my husband … to fly …’) and the ‘paracadutisti’ who, unlike Icarus, don’t perish when their ‘wings’ deflate/disintegrate but press on to fight in the war. The image of the parachute as ‘a shroud / for broken bones and battered skin’ is a haunting reminder that a means of escape/transformation can also be a signifier of that final escape, death.

‘Calvario’ too, invoking a vernacular voice, recreates a sense of the different actors and roles in an Italian village Passion play – particularly Jesus (‘one of the blond twins’ – a son of German migrants) and Judas, the ‘best’ of whom so successfully embodied guilt that the crowd was moved to applaud (did he in fact hang himself?)

‘Skin’ is a brief, witty response to Hu Weiyi’s photographic work 14 Minutes. The poem’s language suggestively memorialises the model’s bodily performance/witnessing (a profane sacredness?) in a kind of undressing reminiscent perhaps of John Donne’s ‘To His Mistress Going to Bed’, as ‘the delicate art of indentation’. Metaphysically different, however, Part IV of ‘At home with Peggy’ juxtaposes an image of the (naked?) sunbathing Peggy Guggenheim amusing herself at the ‘reactions of guests’ to ‘Marini’s sculpture…The Angel of the City’ with ‘the rider’s metal penis / which Peggy has screwed in’.

In ‘The Book Artist’ Russo proposes, synechdochally, an image for his book: a copy of Sylvia Plath’s poems ‘like a taxidermied bird-of-paradise’. Like ‘The Archivist’, this poem is concerned with the question ‘What can/should we do with art/poetry? Does/Can it have meaning beyond itself? ‘It’s a kind of rescue … / … reusing and reconstructing / … the unloved’.

And ‘Thin Silver Lines’ explores an invasion by ‘copulating’ (the word, used twice, seems awkward in the poem – I’d delete it) snails who are eventually fed to the hens, leaving ‘thin lines’ – an image of poetry’s afterimage.

But the museum poems seem often burdened with seriousness/gravitas/significance – maybe the ‘idea of the book’ has taken over. For example the title poem is clearly satirising the farce of American creationism and Russo delights in mocking the naïve and contradictory dioramas, fraught with anachronism and xenophobia: ‘Waist-high, Adam rises from a pool, / Eve beside him – her long hair loose across her breasts, / as though she already knew shame / before eating fruit from the Tree of Knowledge’. In another recreation there is ‘Mary with a California accent’. In one creationist museum there’s ‘a petting zoo where a zonkey and a zorse are exhibited … to create something new, as God has done’. Russo registers the silliness and even blasphemy here but the poem seems uncertain what to do beyond pointing out absurdity and inviting a reader’s assent to its incredulity.

‘A Ponsonby Road Menagerie’ lists objects, emphasising what the poet considers vulgar, pretentious – a reflection of contemporary society’s bad taste (‘bric-a-brac satire’?): ‘a woodblock-mounted rabbit stretched out mid-leap … Prussian suits and autocorrelation sorts …’ It’s a cluttered enumeration and seems a somewhat self-satisfied dismissal of this market/museum of creation.

In several poems Russo’s ‘I’ seems intrusive, parochial, eg. ‘Proust’s Bedroom’ and ‘Phar Lap behind glass’ – insisting too readily on the poet’s subjective opinion/presence/judgement so that the I seems egotistical, petty … In ‘What Voltaire and Rousseau say to each other at night’ the repeated rhetorical questions become increasingly portentous (‘… Does Rousseau mutter in gloom, / War is a relation not between man and man / but between state and state? /while Voltaire laughs and says, See your creatures / of perfection, see them in their natural state? ’) so the end response to the questions is almost ‘Who cares?’ Similarly in ‘When they call a hill a timpa’, there are too many faux questions about caring (about linguistic niceties) which weigh the poem down, pontifically.

Both ‘Walking through Anne Frank House’ and ‘Relics from the Golden Age’ begin prosily. Both seem wistful – searching for belief (‘maybe it’s a talisman …’ and ‘there’s a comfort in observing …’) and, as in the poem about Freud ‘The Study, 20 Maresfield Gardens’ – wanting, in a teacherly fashion, to mythologise objects (‘the petrified porcupine … The Baboon of Thoth … ‘) to ‘interpret’ these musuems .

However the dramatic ‘In the Museum of Natural History’ meditates on the preserved dissected cadavers, brilliantly contrasting with tourist buses and the preserved hippo. On the other hand, ‘Museum of Creativity’ starts arrestingly (‘A museum of x-rays … the bones of paintings smeared with new coats …’) but becomes an unconvincing, folksy ‘simple studio’.

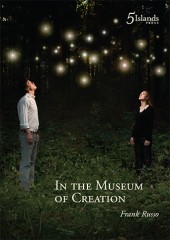

This is a collection obsessed with the idea of museums and memorialisation, with wonder and irony. The poems are interested in ossification/fossilization and renaissance. There is a searching for significance – both of the ‘original’ and of the recreated, as well as a playing with conflicting, destabilised notions of what is believable, important in others. For me this is echoed by the front cover photograph’s 3D-like fetishisation contrasting to the blurry author pic on the back. The strength of In the Museum of Creativity is the profound ambivalence that runs through the volume – Russo’s oscillation between satire and enlightenment, between mockery and embrace.