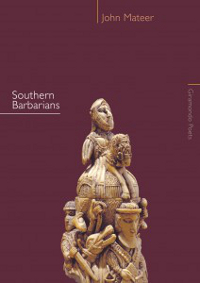

Southern Barbarians by John Mateer

Giramondo Publishing, 2011

Southern Barbarians is a book that explores both the colonised and the colonizing impulse through the inflections of the Portuguese epic Os Lusíadas by Camões, the explorer/soldier/poet-traveller and heroic poet of the Portuguese. The book ranges from Lisbon to Macao, taking in Indonesia, Malaysia, Warrnambool, and Japan on the way. This is a world where African businessmen in Macao see ‘African wildlife’ in a travel agent’s window, in an image of savannah they are no closer to than the Macanese.

Brian Castro notes Mateer’s concern with the question of literary ownership. Mateer has made of wandering and exile from his birthplace of South Africa, a means of dismantling the clichés of a Pico Ayer style ‘global soul’. The world’s privileged (including its artists and writers) have unprecedented means to travel the globe and to wear the trappings of happy hybridity, but no easy means to overcome alienation from the native’s deeper and more authentic experience of their place. Mateer’s achievement is another archive and critique of the moments of connection of tourist/poet with the other. But the book is more than a travel diary: it is an impressive poetics of the inarticulate, the unsayable and what it means to make sublime cultural connections with the other. Contact occurs as much outside of language as inside. In poems that address Zen Buddhist practice, Mateer shows how we can know through forms of perception and affect what this unspeakable is. Mateer’s book is wonderfully generous and sensitive to the economy of difficult cultural encounters.

Mateer’s poetry has always been aslant of much of Australian poetry. If emigrant poets suffer, it is to be perpetually underrated compared to more nationalist poets. Again, Southern Barbarians wrestles with the question of how voice and nation work together, either as a tag team or as adversaries. This book offers no easy answers on that score, but mines the division of lyric from person, land from owner, imagination untethered to epic or imperial destiny. Mateer’s tribute to literary precursors is teasing and ironic. Its intertextuality is evident, but lightly and affectionately indulged: Baudelaire, Lorca, Éluard, Breytenbach, Pessoa, and Camoes. What poet would not want to be remembered as a massive public statue? Who doesn’t want his or her works translated for all time as a national hero for everyone? But then, the valorisation of The Author as Public Property is not the aim and Mateer is not travelling to find himself, unlike those who hawk ‘a book of photos of The Poet gradually disappearing / on the beach said to be Maputo’ (‘Eduardo’). Who is Mateer, and who is the Author but a wearer of masks, a serial user of Pessoan heteronyms, or a mess of personae operating under more than one false name?

Whether Mateer is a tourist, Australian, South African, poet, art critic, or Southern Barbarian of uncertain ancestry, the book is written in a spirit of ‘disembodied irony, travelling to, and coming from, other worlds’ (from Castro’s ‘Introduction’). But unlike a lot of books on travel, this is a mournful book of saudade or sadness in Portuguese, with the sense of nostalgic longing, of the exile and of the deterritorialised voice. The poet records the sadness that infects the colony that suffers its distance from the centres of culture. It is the sadness of suffering undergone by the dispossessed and homeless. In ‘Angela’ he writes: ‘Poeticising shelter is another way of speaking loss’. Above all, it is the sadness of poetry confronted by its own dis-articulation and its marginality. Such is poetry’s nostalgia for the epic function it once enjoyed, or perhaps still enjoys in tiny pockets of the old empire, where the traces of grandeur persist in the figure of a custard tart in ‘An Essay on Sweetness’:

There is the idea of the perfect colony; for instance, Saint Augustine’s City of God. Then there is the Empire of Nostalgia, inhabited by inebriated poets, its laneways and tiny late-night bars manifold and luminous as the cell of the brain ... Yes, we have Bartololomeu Dias and Alvares Cabral but more important are the pastéis de Bélem of decolonisation.

It is also, simply, the pathos of the heroin addict, the sailor stuck on shore, or the demobbed soldier. Despite this nostalgia, Mateer’s cosmopolitan voice is a generous one that tests solitude to the limit without rejecting the social encounter. Mateer in the guise of poet of the bar, the flaneur, encounters the aporias that emerge in his attempts at communication and the occasionally dark search for the erotic encounter. There is, ominously, the risk of a terrifying disconnection from the other. Moving outside our comfort zones, there are moments of conflict and violence. Before we can love the other, we must overcome fear, make an approach and speak; before speech we must pursue the code.