The author’s playfulness is to the fore in this strange, charming book. It is a game which invites the reader to roll the dice, take a card from the deck, gain points, lose a turn, and, one way or another, advance around a notional game board: a pirate’s world of exotic ports, risky encounters, escapades, wonders and the routine of shipboard life, always in the presence of the moody, changeable sea. The cards that guide us are like entries from a log in which, generally, the captain speaks in the second person. Some are as brief as a phrase (‘Mast struck by lightning’), others a couple of taut paragraphs. Patches of narrative and patterns of repetition emerge from the sequence, which we might ‘reshuffle’ to create our own order. Variation is part of the game.

More than once we are advised to head south for the nearest landfall or into the setting sun, ‘against which you will be hard to see’. ‘You’ is the captain, whose company in these little monologues and reported dialogues we come to appreciate: the concern for the crew as they ‘polish, splice, caulk, clean and paint, hammer and polish and mend, uncomplaining …’, and also sing, dance, dream and fear; his line in wit and irony; the understated wisdom; a flash of melancholy that turns as quickly to good humour: ‘A vision appears to you of the former ship’s dog, much loved by the crew. The dog suggests – in a friendly way – advancing doom. This is neither here nor there.’ The captain’s tone keeps the enterprise afloat. His ‘you’ is himself, his ship, the player reading the card, us. And sometimes it is not the captain, for the captain is observed on occasion – slipping on stairs, stricken by illness.

A bizarre juxtaposition in this piratical imaginary are the cultural references that bounce around, with jokes aplenty for the cognoscenti. ‘A microwave’ somewhere in the future making ‘Wavelets for the little tackers of Hawai’i’ (groan). The ships that the captain encounters – female according to tradition, with dangerous women in charge, mostly named for movie and television stars of a bygone era. Margaret Rutherford in charge of the Margaret Dumont, for example; Javier Bardem, appropriately Hispanic perhaps, at the helm of the Vivian Vance, if you know who she was (Lucille Ball’s redoubtable sidekick in I Love Lucy). Edie Sedgwick from the Warhol Factory appears, as does Argentinian writer César Aira’s novella Varamo. So our ship sails on, from Kowloon to Valparaíso. The roll of the dice is the rule of a game which deals in allusiveness and welcomes sideways moves.

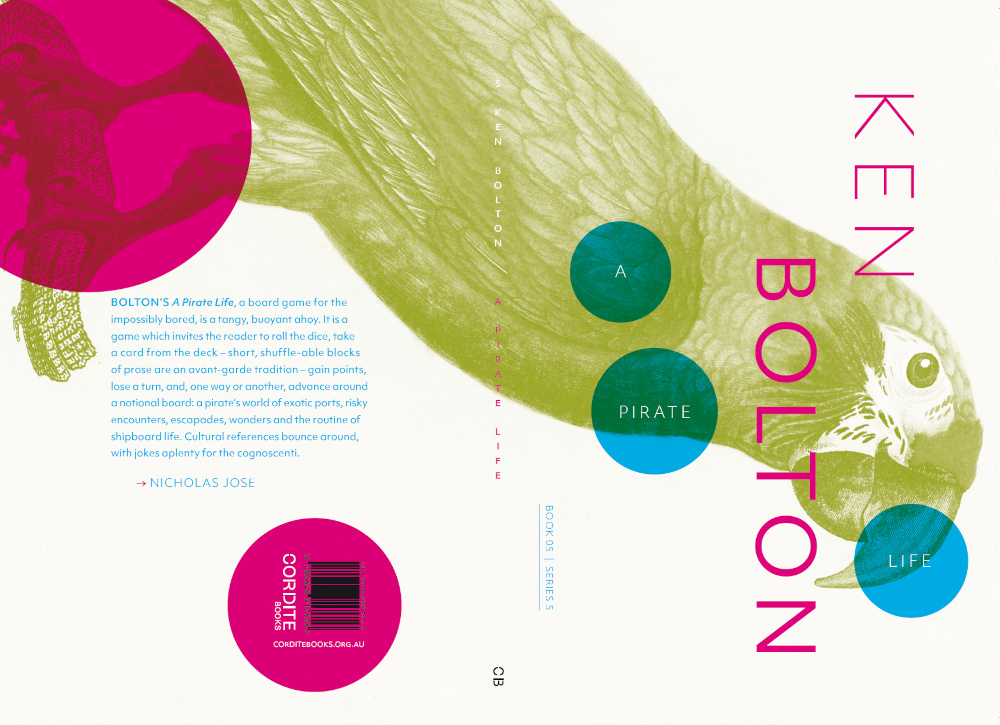

Proposing life as ‘like a board game’, A Pirate Life is, I suspect, family fun too, playing with authorial obsessions and bringing, I think, the writer’s home life into the scene. The reader will never know. Fans of Ken Bolton’s poetry, fans of the Lee Marvin readings he MC-ed, will recognise this flaneur of the high seas, ‘jaunty’, ‘insouciant’ (favourite words), reflective, resilient, as ever. Short, shuffle-able blocks of prose are an avant-garde tradition. So many ways in-between, of no fixed abode, prose poetry is a sign of freedom and innovation. Is that what’s on the cards here? Bolton’s A Pirate Life, a board game for the impossibly bored, is a tangy, buoyant ahoy.