What characterises Dan Hogan’s poetry is the way that, each time we come close to fully apprehending the impending collapse of capitalism, we are waylaid by something more urgent and mundane: groceries, emails, calls to Centrelink, traffic jams on the way home from work. When the present is frantic, frenetic and demands our full attention, it becomes the only thing that is real. The tragedy with which we live, in Hogan’s words, is that we resultantly have ‘no time to grieve for lost futures’.

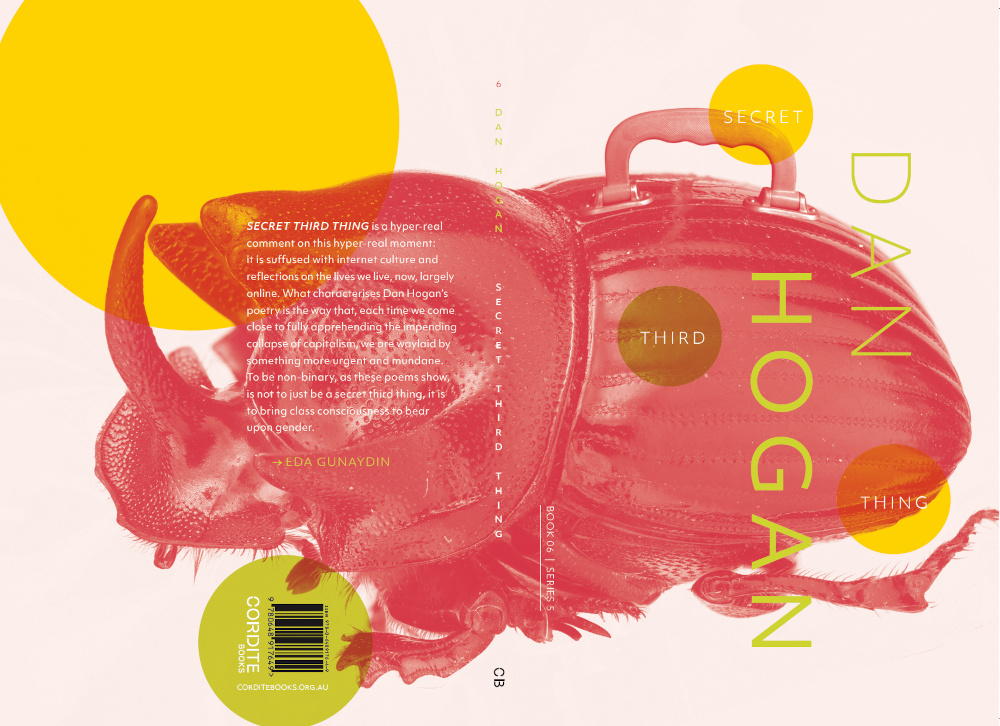

This line, as do others in this collection, recalls Mark Fisher, specifically his contention that late-stage capitalism had caused the cancellation of the future. Unable to imagine alternatives to the present, he and other Marxist critics like Frederic Jameson noted the tendency of this epoch’s cultural products to be capable only of referencing themselves, with the future foreclosed, and attempts made to summon the past landing flatly as nostalgia and kitsch. Starting with its title, Secret Third Thing is a hyper-real comment on this hyper-real moment: it is suffused with internet culture, memes, self-referential quips we make to cope, reflections on the lives we live, now, largely online, inter-cut with tongue-in-cheek evocations of the Irish pastoral.

But the past, the present and the future are not secrets. Hogan knows ‘not that the world is going to end, but that it has already ended.’ They also know that our cultural outputs form part of the circuits of capital which they are designed to critique: the collection is haunted by these digital traces, of algorithms, sold data and optimised desire. This is another thing that Fisher wondered, whether our desire to push beyond capitalism is inevitably always co-opted by and absorbed into capitalism. But Hogan is not escaping into being what we might call extremely online. They are not posting jocular outrage kitsch like, ‘Rude epoch. How very dare’. They plainly ask: ‘You think this is funny?’, and later answer their own question: ‘Elsewhere, glops of jokes make their way into a status update. It is an annihilative transaction largely misunderstood.’

The task for this text, like others with Marxist sensibilities – like Elena Gomez’s Body of Work and Astrid Lorange’s Labour and Other Poems – is twofold. The first is to clear up the misunderstanding at the heart of this annihilative transaction, by raising class consciousness. As Fisher knew, as Hogan does, the petit bourgeoisie has ways to prevent the topic from coming up. But Hogan insists on breaching decorum, noting repeatedly how capital perseveres through class: our familial bonds, addictions, symptoms, genders. To be non-binary, as these poems show, is not to just be a secret third thing – as the joke goes, not a man and not a woman – but to, much more seriously, bring class consciousness to bear upon gender, to ensure that whatever else non-binary is, it cannot ‘match the interests of capital’.

The second task for the Marxist poet is to summon onto the page transactions that are not annihilative. Our lives now are structured by the prospect of an ultimate annihilation: the trillionaire class versus the collapsing biosphere. Hogan writes: ‘the world isn’t big enough for the two’. Above anything else, then, this collection is a work of dialectical materialism. It not only insistently names class struggle, but also highlights its generative potential: the notion that the opposition of the two classes may not be (only) destructive, but lead to the creation of something else: a third, new thing.