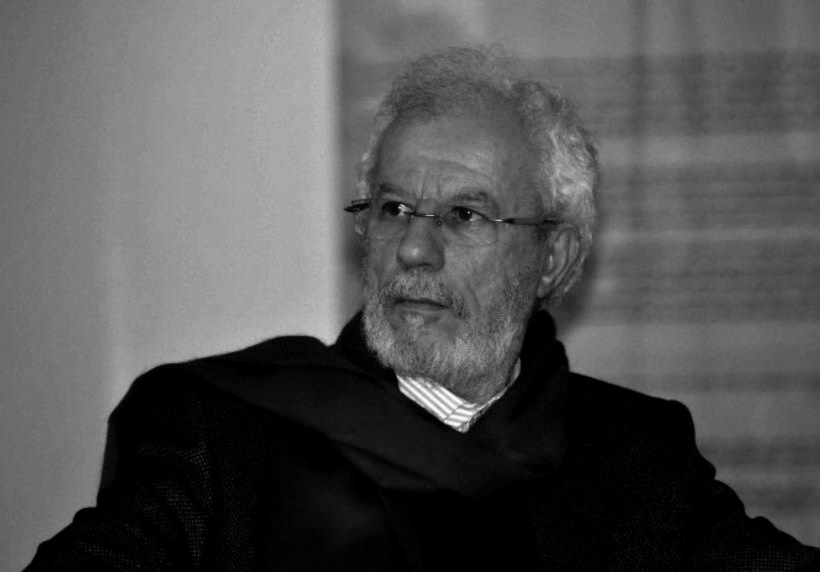

Image courtesy of Mohammed Bennis

Poet and translator Mohammed Bennis began his career as a poet in Morocco in the 1960s, at a time when the free verse movement was taking the Arab intellectual world by storm with the Beirut-based journal shi’r, with the Syrian poet Adonis at the helm.

Bennis is not a poet with a cause. He is not writing for Palestine or for women’s writing in the Arab world, themes which are easily snapped up by Western audience. Instead, as one of the more innovative language poets, methodically tampering with language in a dialogue with language itself, Bennis has refused to be either local or international, a strain of consciousness that may have something to do with the geo-cultural location of Morocco itself, a conundrum of the Arab world, Africa and Europe.

Angelina Saule: When you began your career as a poet in the 1960s, did you feel influenced by the free verse movement taking place in the journal shi’r founded by Adonis, or by the events of ’68 in France? Which form of freedom and which task of liberating language seemed to have made their mark on you most?

Mohammed Bennis: When I began to write poetry I felt influenced by free verse in Arabic, as in the poems of Badr Chakir Essayab, but a few years after that I discovered Adonis. In the same period, I was reading French and German poetry and I was in Paris during the summer of ’68. Those events have had together a great influence on my thinking and my writing until now.

AS: How exactly did the events of ’68 in Paris affect you? What insight did they provide in terms of a free vision of language in the Arab world?

MB: As you know, the events of ’68 were a revolt against all traditional ways of life. To change Arabic language by using new forms and new styles was like a second coup. My new method has taken time. At last, I have transformed the many manners of writing.

AS: How do you see the innovations taking place within the Arabic language now? Are we still in need of a poetic revolution?

MB: The innovation within the Arabic language was great. It was a new Arabic or a modern Arabic coming into being. It was intensely different from classical Arabic writing, and this innovation motivated a poetic revolution in countries of the Maghreb.

AS: You have made a shift in terms of revolutionising certain poetic forms of expression – can your contribution be considered to be a part of this revolution?

MB: Maybe I have created a minor revolution. I am sure that I have only changed the manner, because changing the manner of something is not always a minor or major revolution. Change is a step, but it is not enough. On the other hand, literary life is difficult, and we are not able to accurately judge what we are doing or writing.

AS: Do you feel that your writing has begun the path of a poetic revolution in the Maghreb? Has your writing greatly informed new poets in Morocco?

MB: When I talk about manner, it is only a kind of observation concerning my own poetic method and its evolution. I have studied the rationale of a literary revolution in modern literary Arabic and I have found that so far it is not possible to accomplish this revolution within the Maghreb. We need time to see clearly what is happening. I only know that I must continue writing. Nothing else matters.

Bennis’s answer made me reflect on the Arabic phrase ‘Cairo writes, Beirut publishes and Baghdad reads’, which attests to the long-standing division of literary and intellectual labour in the Arab world. For a wider historical context, the literature of al-Nahda, the renaissance of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, is usually viewed in terms of Egypt and Greater Syria. The peripheries of the Arab world (from Mauritania to Oman) are rather unknown even within the cultural fabric of Arabic life, with the exception of such writers as Tayeb Salih or Mohammed Choukri. The exodus of intellectuals from the centre of the Arab world to exile communities abroad at the beginning of the twentieth century not only created a bridge between Western literary developments and individual Arabic innovation, it also led to a certain trend or stereotype about the origins of the pulse of experimentation within Arabic poetics.

AS: What motivates you to change syntax the way you do? Are you seeking to make ‘the invisible’ – the absence of what is not in standard language – present?

MB: Poetry uses the standard language but all changes occur in the process of writing. If the poet uses the standard language, he writes in his own language. Using the standard language does not mean poetry is standard. Never can we say that. Every poet creates his own poetics and his ambition is to touch the impossible, to write the ineffable. How is it possible to not make the visible invisible, but to give the invisible a new life? This is the question.

AS: Which form of Arabic do you feel more comfortable writing in, Moroccan or Classical? Not long ago I was at a hakawati reading in Fes, and it was easier for me to understand most of the Classical verse, but rather difficult with the Moroccan-speaking hakawatis, although they were more engaging for the audience. (This reminds me of zajal in the Levant among the various mountain communities of the Druze and the Maronites, resuscitating the idea of the actual and the artificial within the one language.) Is there a preferred register for readers and listeners?

MB: Writing in modern Arabic is a choice. We must not confuse the situation of Arabic with the occidental languages, as we have another history. Unfortunately, we suffer from several factors, including education, and sometimes the problem is not clear. Maybe one day we can resolve the problem of languages in the Arab world. Maybe it is possible in the future.

The problem Bennis refers to here is the diglossia of Arabic. The written form has remained constant since the Quran, not having changed drastically until now, and is used in modern print media (imagine reading The Economist in the Anglo-Saxon of Troilus and Cressida), while the umma (dialect), which reflects regional differences in temperament and cultural background, is vastly changing lexically and grammatically according to local and foreign non-Semitic influences, making the various dialects mutually unintelligible. The written form bespeaks education, literacy and, perhaps, religious instruction, while the spoken adheres to the day-to-day profane (as opposed to the sacred written form of pure Arabic), generating hierarchies within the language.

AS: When you say ‘modern Arabic’, do you mean MSA (Modern Standard Arabic)? Do you ever feel the need to meld MSA with the flavour of Moroccan Arabic?

MB: Yes, I use the Modern Standard Arabic, and I use Moroccan Arabic when I feel it is spontaneous, when it is the expression of my body. This is normal, and we find the same comportment in the writing of other Arab poets and writers. The result is the Modern Arabic language.

The vernacular is, as Bennis expresses, something more deeply felt and physical in comparison with MSA: it is a labyrinth of identity oddly proud against the column of standardisation associated with MSA. As I write, I myself am surrounded by the clipped quaffs (ق) of my father’s people in Mount Lebanon, making my background easily heard when I am in the capital twenty-five minutes away; the overall vernacular of Lebanon chooses to speak without this particular letter. (It is rather bizarre to be told several times to drop the letter in a language I feel rather at odds with or baffled by; thankfully, I don’t write poetry in it.) It is important to deviate slightly into the field of phonosemantics to impart the significance of the basic phonemes of Arabic – especially in order to ascertain difference. It is claimed that certain checkpoints of the Phalangists during the Lebanese Civil War posed merely one question, which was to ask people to pronounce the word for ‘tomatoes’. The Palestinians pronounce it differently from the Lebanese, and thus fell into a linguistic trap and were killed in an instant for their accents.

AS: As a poet writing in Morocco, do you see yourself on the threshold of al-Andalus and the Arab world, or on the threshold of the Francophile-Moroccan world? Which axis do you feel informs the majority of your work? In the poem ‘I am not I’, you write quite beautifully about this:

This is my law – To reveal secrets to ardent lovers In Baghdad and Fes, In Cordoba and Qayrawan, To accompany a tear to its burning anxieties, To bless a rose on its way between a sweetheart and a lover, And write to you About this seed which is sufficient For everyone who is In the presence of madness On the paths of hearing and seeing

MB: I do not have a difference between the two worlds. Since the beginning, it was clear to me that I need to understand the two worlds, as they have their traces on my body. The problem is not to choose between the two worlds, but how to be free in relation, vis-a-vis yourself and the other.

AS: How would you describe the movement of the traces of the two cultures on your body? Do they dissolve, disappear, etch, mark or do something else on your body? How do they move when you write?

MB: The trace of the two cultures means that my body is cultural. It also means that the two cultures are inseparable in my vision and my manner of thinking or feeling. I cannot separate this plural sensitivity in my words. For this reason, I believe I am writing in modern Arabic and it is the result of the two cultures, a sign of intercultural being that affects the culture of our world.

AS: Is there a particular school of Arabic poetry that mirrors some of your own poetic concerns? For example, the poetry of Jahiliyya, the Abbasid court poets or the al-Nahda movement?

MB: No, I do not think that is a particular school. When we write in Arabic, all Arabic poetry is your patrimony. I add that it is normal for me, as a Moroccan, to have an interest in Andalusian poetry. If you read my poetry, you find the poetry of Jahiliyya, the Abbasid court poets, as well as many international poets: all poets of the world are my family. The difference lies in language only.