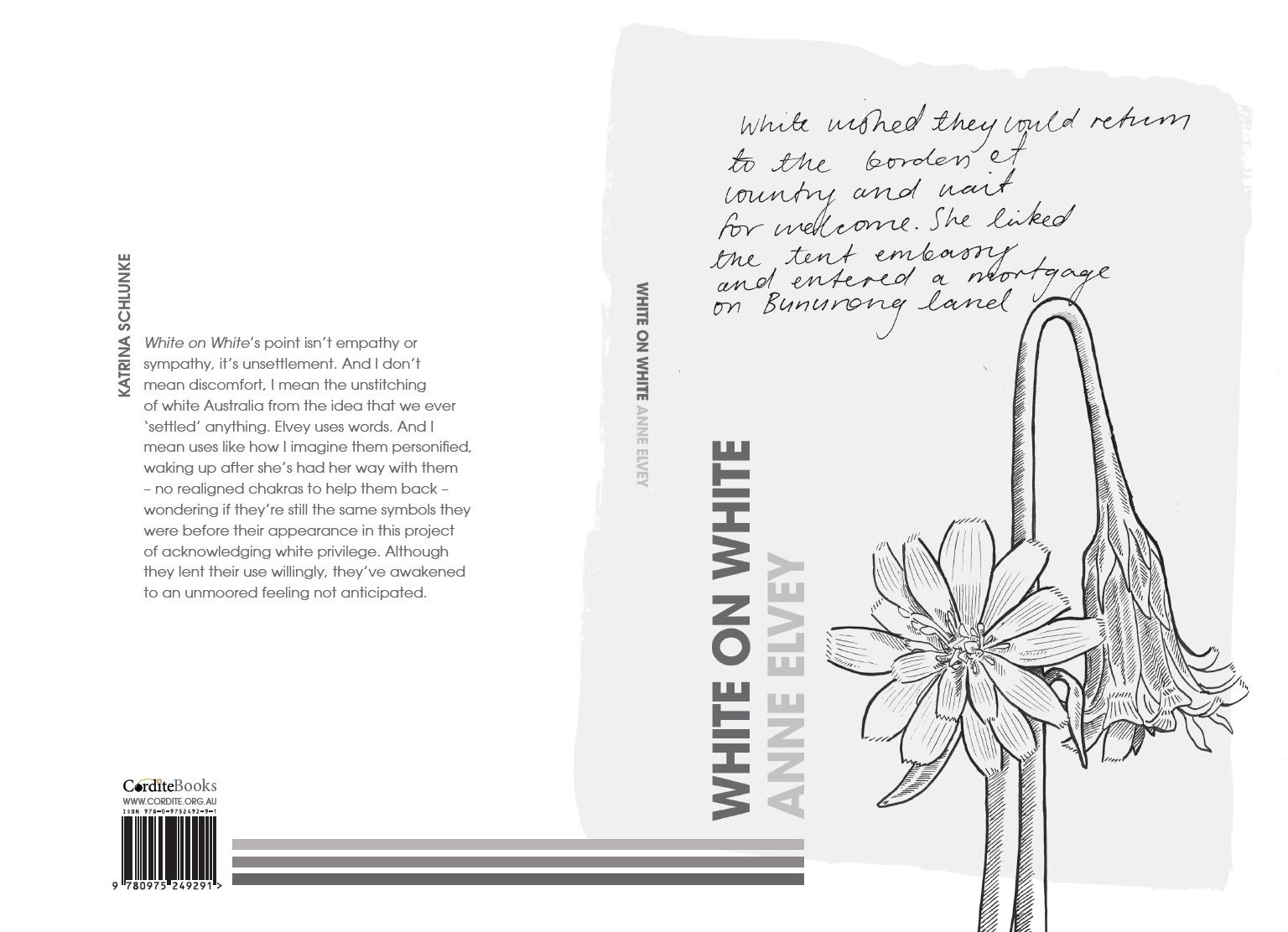

Cover design by Alissa Dinallo, Illustration by Lily Mae Martin

What is happening in these poems? Or do I mean what happens to us, the readers? But which ‘us’? And what reader? I am not really talking about feeling, although who couldn’t, wouldn’t, feel when ‘School Days’ – a poem that records every detail of white skin and soul, sun-warmed government-issue school milk and British ritual in one colonial Australian home – has another child, likely an Indigenous Australian child, stolen ‘while waiting for a train’. This is a crystalline evocation of the public secret of the removal of Australia’s Indigenous children from their homes and communities, which began as a sporadic technique of settlement in the early days of the colony, became an official policy of assimilation in the 1900s and continued right up until the 1970s. But White on White’s point isn’t empathy or sympathy, it’s unsettlement. And I don’t mean discomfort. I mean the unstitching – through the interrogative deployment of one uncanny image after another – of white Australia from the idea that we ever ‘settled’ anything.

Although I have identified a connective theme, don’t for a moment think there is a sameness to the poems that follow. Rather, they operate with the necessary mix of adaptation and surprise that tactical warfare demands. Elvey’s poems use the spatial possibilities of the page: hiding some words within gaps, sending others to the raw edges and pushing yet more into compressed packages as if an introduction to something greater … closed fragments fallen from another tomb. They show their sources and, in so doing, march us in to ask complicated questions of historical ‘truth’. What more than ‘report’ does any report do?

In White on White, Elvey uses words. And I mean uses like how I imagine them personified, waking up after she’s had her way with them – no morning-after pill, no realigned chakras to help them back – wondering if they’re still the same symbols they were before their appearance in this project of acknowledging, perhaps even dismantling, white privilege. Although they lent their use willingly – took drugs, gave permission – they’ve awakened to an unmoored feeling not anticipated.

Sometimes the words are simply left to bleach in the sun, marooned by the impasse they produce. Look carefully at ‘Five ways of graphing colonisation’ and see how the lines

Terror nullius of empire, imprints my retina, press, of moisture, on a cheek

effect a very different politic of white distance when distributed across the page like forgotten huts on unused hills. Other words are made to churn up the gaps between colonial and Indigenous Australian philosophies, and between ideas of Country and notions of land owned, settled, fought for, inherited, mined, farmed, schooled and stolen.

Listen to these sentences removed from the whole of their original poems: ‘What ticket is inherited for title?’, ‘the unhurried hazard of the banksia counters / the raised pulse of the dash’ and ‘I put my hand to the twitching rod / lend my ear to the ochre ground’. Tiny phrases that worm their way under our suddenly very noticeable skin. This collection is not the bomb or its blast in an old-fashioned war; it is an attempt to unsheathe the non-Indigenous from the idea of an ordinary skin. Perhaps all of these poems can be explained by the poet’s admission that there once was a time she mispelled ‘seperation’ and on her ‘desk the whiteout / is shelved beside the pens.’