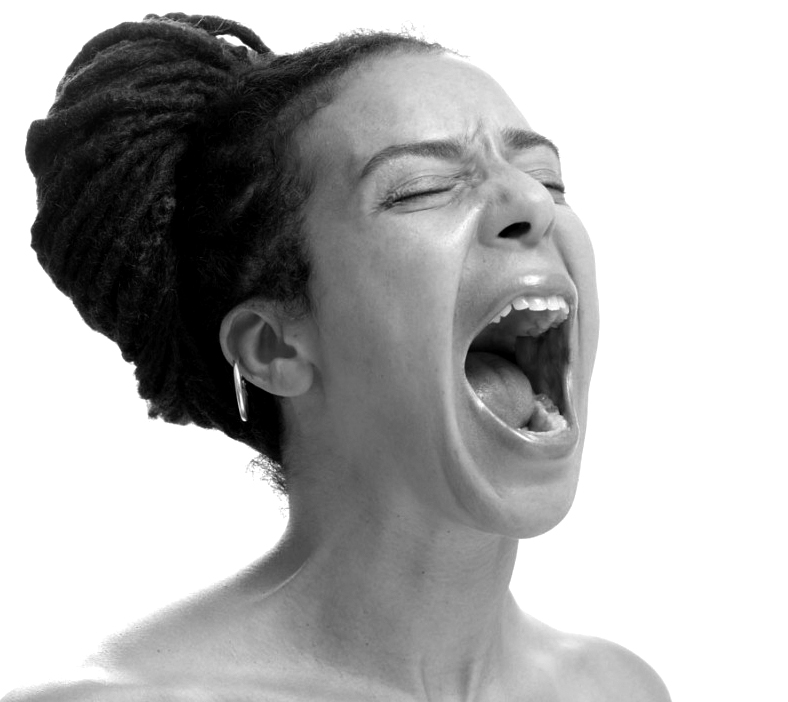

Image from The Great Black North

Tanya Evanson is as generous of spirit as she is on stage in the hour we spent on Skype from a sunny, mosquito-netted room in Antigua, following an email correspondence. She has the knack for bridging gaps, and we have a shining moment or two when space collapses, her eyes go wide and her hand rests on her heart. What’s the Internet anyway if not an interstice that leaves us all ghosts, ready to be touched without being touched?

Clearly she’s finding some of the solitude in Antigua that complements the moments of intense connection she facilitates as an artist and teacher, and connecting is what her work is all about.

‘I am the Muse’s bitch. As such, I do not decide what should be written, but try to capture epiphany as it hits … if I get in the way of these things, I am lost.’

If that sounds esoteric, it’s appropriate – Evanson’s been a Sufi student for the nearly twenty years she’s been performing her work.

We connect easily over our shared passion for performance poetry and the challenges it poses: to practice this art is to be forever negotiating the tension between the ephemeral and the permanent. Oral literature – dub poet Lillian Allen prefers ‘Orature’ – is fundamentally transitory, or so we say, but each experience is (most often) the delivery of a persistent text.

So, is a performance more an act of writing or an act of reading? Probably more an act of balancing, and Evanson is known to find a harmonious posture on stage. Maybe this is not as contradictory as I make it sound, especially if you consider the way that Evanson applies her studies of Buddhism and Sufism to her work. She calls herself a ‘Bothist’ in rejecting either/or propositions, and remembering that each story or fact is incomplete without its shadow.

But what happens when things get off kilter? Evanson has thoughts on this with regard to current Canadian spoken word. She was one of the poets of honour at the 2013 Canadian Festival of Spoken Word (CFSW). The festival, with a national team poetry slam as its core and other spoken word events to complement it, has chosen this way to honour ‘elder’ performance poets – two per year – who have a core role in fostering the national community. Evanson’s nearly twenty years of performance have certainly touched most places in Canada.

From Montreal to Vancouver and now cycling back, Evanson had a bilingual childhood with biracial heritage and bicultural roots in Quebec and Antigua. She sojourned in South America and then studied Sufism for years in, naturally, the tri-continental country of Turkey.

No wonder she emphasises that poets must find unity through multiplicity. But our scene, she worries, is too dominated by a single path.

‘Canadian performance poetry is currently so overwhelmed by the SLAM tradition that anyone working under the vast umbrella of spoken word is often labeled a SLAM poet. We need to shift our focus away from art as sport.’

At the same time, Evanson acknowledges that what has been built with tremendous loving care, around both slam and national competitions, is a community. Some inspiring conversations about caring for one another and inclusivity have resulted from this nesting activity. She cherishes this, but wants more poets to fledge. In her view, intimacy (personal or cognitive) must give way to separation in order for the journey to be complete. Each artist is on a path, and Evanson seems to feel that we are gathering on that one stepping stone where competition and ego are potential downfalls.

‘Granted, SLAM is part of our education, but there are three levels of learning: reception, digestion, and separation. We are fixated on the first two. It is like receiving treatment from a doctor who is still in medical school. Poets are doctors of the soul! We must graduate! Leave the controlled environment so that the work may fly into global, radical, experimental, limitless, cosmic possibilities for change.’

The pedagogical analogy fits. Evanson is a key mentor, or a shepherd of mentors, however humble she may be. Currently, she is Director of the Spoken Word program at the Banff Centre in Alberta, which Sheri-D Wilson began after consultation with poets and organisers from across the country. That consultation, near a decade ago, was driven by seemingly contradictory impulses to preserve the vitality of the spoken word, while somewhat professionalising – or at least taking seriously – the establishment of a critical record.

Now, each spring in Banff, successful applicants gather for a guided residency in spoken word performance. Participants have generated fringe festival shows and recordings from the experience. Faculty has included the likes of Evanson, Emily Zoey Baker, Lillian Allen, and Bob Holman.

This program is vital. It could be described as a heart for the circulatory system of spoken word poetry in Canada. It’s remote, but no retreat, and participants have frequently described it as a rite of passage in their artistic development.

Does that mean its director has an agenda for where Canadian spoken word should go? Humility won’t allow her to express it as such, but she does feel there may be an imbalance to address. Once again, Evanson’s Bothism guides her thinking. She believes in the conjunction of the near and far, of community with solitude – something that Banff evokes for all of us who’ve spent time there with our writing.

In applying this Bothism, the arbitrary, anti-expertise ethic of choosing random audience members to judge slams is intended as a counterpoint to the stultifying (or at least exclusive) effect of a qualified critical class. But she sees a potential danger here in overcompensating for such expertise. She talks in deliberately non-judgmental terms about each artist being on their path, but does not ignore the possibility that those paths may lead us astray. She points out that we do not have much of a critical record, and little that could be described as an aesthetic credo. Instead, there’s a vivacious community of mutual supporters and enthusiastic audiences, where a five-year veteran can be valued as an ‘elder.’ There’s also a connection between the program at Banff and Litlive.ca: The Canadian Review of Literature in Performance, and we can trace ourselves back to Victoria Stanton and Vincent Tingueley’s history book Impure: Reinventing the Word. In essence, we do have some kind of tradition – one Evanson says we need to foster and help create more stepping stones and connections. Reaching beyond the Canadian experience, she admires players in the Australian spoken word scene like DJ Lapkat (Lisa Greenaway) and the journal Going Down Swinging, which both bring a critical record to current work.

She holds dear the spirit of exchange, and this issue of Cordite Poetry Review includes Evanson’s poem ‘Finishing Salt’ about seeking and letting go of a counterpart.

‘It is an honouring of time spent observing something as it ends, in this case, a long-term relationship (my 8-year marriage) ending in tandem with autumn on Galiano Island, British Columbia. Both are holding on to the crescendos of summer but death is inevitable.’

So there we are again in the present moment, and the present transmission.

In fact, it’s when I broach the topic of this occasion – this publication, and its reaching out from one hemisphere to another – that her hand goes to her heart. She mentions an urge to have a group of Canadian poets go through Australia, as have C R Avery and Shane Koyczan have recently done. She expresses gratitude to Australian spoken word poet Emily Zoey Baker, who was on the faculty at the 2014 Banff program. She talks especially about how much it means for her that ‘winter and summer exist at the same time on this planet, day and night exist at the same time on this planet, each is a fact.’

In Evanson’s Bothism there is clearly something – not quite a longing, but an alertness – that looks always to the completion of a cycle, or to the turning over of a coin to see its other face.

Being a spoken word performer means living not in paradox, but at an intersection where the ephemeral and the constant define one another. Here, the balancing act is a dynamic equilibrium to seek, yet maybe not achieve.

Evanson’s a student preoccupied with teaching, a vocalist studying silence, a traveller concentrating on the present – a good description of a refined practice of Sufism. Rumi too, we remember, had much to say about silence. To negate ego and to perfect a worshipful posture is more than an esoteric tradition, and it may be just the sort of guidance our spoken word community is looking for.

Tanya Evanson is proud of her work at Banff and the artists she works with, but she has a wish for us: not to have it both ways, but to turn and return, seeking the place where both paths are in fact one.

Pingback: Current English Ottawa Poets – Pearl Pirie