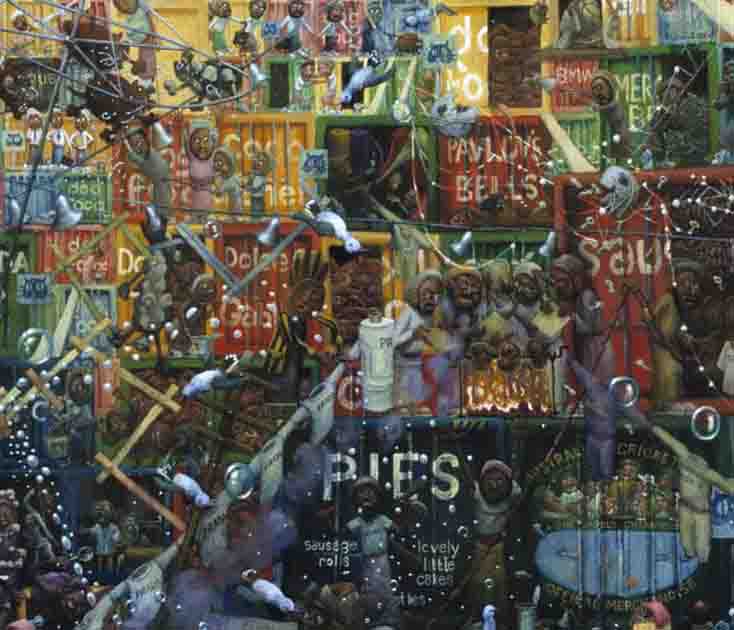

Detail from Cameron Hayes's 'The rescued refugees had to live off what was on the container ship which, because it was headed for Australia, was full of pet food and fake Italian fashions'

Cameron Hayes is something of an enigma in the contemporary art world: he doesn't live in London, New York, or even Sydney or Melbourne in his native Australia. He lives on Melville Island off the northern coast of Australia, a large island which has a strong Aboriginal arts community, many large crocodiles and very little else.

Cameron Hayes is also an artist who paints big narrative pictures. Most people in the art world today consider big narrative pictures retrograde and, despite having been a finalist in every major art prize in Australia, and having had two successful solo shows at Feldman Gallery in New York, many of Hayes's fellow artists continue to sneer at or patronise is work.

'I think the plastic arts are so quaint,' said one successful Australian artist when she was asked to comment on Hayes's work several years ago.

Not only does Hayes paint big narrative pictures, he has also spent most of his painting life trying to say as little about them as possible, allowing viewers to explore his detailed canvases without roping their imaginations down in any way. An admirable principle, no doubt, but Hayes's reticence has not helped him attract the kind of media attention that other lesser artists have enjoyed, nor has it given him the recognition he deserves as one of the great satirists of his generation. The narratives composed within each painting are as biting and strange as Evelyn Waugh on acid, and there is something of Hogarth's forms in the twisted faces of the figures. These small and finely painted figures play out their predetermined roles across the canvas, staring out with bewildered or fierce expressions on their faces, bemoaning a fate they cannot quite grasp. 'Why am I here?' they whisper. 'What's it all about?'

Well might they be bewildered! Hayes's paintings are like Pollock's drip paintings – with every drip metamorphosing into a tiny human figure. When people first encounter these paintings, they look no less confused than the subjects depicted on the canvas. They stand before the painting and search, with subdued agitation, for a reference point from which to start their journey. 'Where do I begin?' they appear to ask these chaotic images. There is no simple answer to this. Unlike the formal designs of Renaissance and Baroque narrative paintings, where a strong sense of diagonal or rectangular line directs the viewer toward the key figures on the picture plane, Hayes's paintings lack any obvious centre. The multitudinous scenes need to be approached individually; you ought to get down on your hands and knees, so to speak, like a Baconian scientist, and sift throughout the visual data. There is no guarantee that you will come up with anything akin to clear meaning, but you will wonder, and you might note how each scene is linked seemlessly to the scenes surrounding it. This is the amazing thing about Hayes's paintings: they hold together compositionally despite the chaos, in the same way Goran Bregovic's musical compositions tarry dangerously on the edge of the abyss without ever stumbling in. It requires a breathtaking confidence to control such visual anarchy and produce pictures that, nonetheless, retain a strong aesthetic.

In his painting, 'The rescued refugees had to live off what was on the container ship which, because it was headed for Australia, was full of pet food and fake Italian fashions', we see a large group of Afghani refugees stranded on a cargo ship that had been banned from entering Australian waters. The refugees have emptied the ship's containers of their contents and set up house inside the steel boxes. They look like the inhabitants of a high-rise ghetto. As the title indicates, the ship's cargo included fake designer label clothing and dog food, so groups of Afghanis suffering malnutrition can be seen wearing faux Gucci suits and Prada gowns while eating Pal.

This is not a painting that is trying to manipulate the viewers' emotions. We are not driven toward any kind of emotional response, any sense of pity or outrage. Looking at a Hayes painting is something like watching the news on television: the distance, the context, the ultimate lack of any direct reality prevents us from having any genuine emotional engagement. In the same way television serves to dehumanise human suffering, Hayes's paintings fail to induce an emotional response because his figures are dehumanised, retaining only some formal qualities of human beings (a head, two arms, etc.) 'I guess what most attracts me about a story,' Hayes says, 'is when people's perception of reality is challenged by a cataclysmic event, or when they are confronted with a differing perception of reality. I'm not really interested in people's emotional responses to their experiences. I'm interested in how they try to overcome their emotional responses. People invariably find creative and elaborate ways of maintaining their perception, against all the available evidence, rather than questioning their perception of reality.'

A clear demonstration of this can be found in Hayes's painting, 'Today hardly anyone could forget yesterday', which depicts the early white settlement of Australia. Despite stark evidence to the contrary, the English settlers persist in believing they are still living in England, wearing English clothes, watering English gardens, playing English games. In another painting, 'From the air we all felt sorry for the sick and starving,' a planeload of tourists crashlands in a famine ravaged Eritrea on route to Europe for holidays. The survivors, having pulled themselves from the wreckage, proceed to take out their cameras and take snapshots of the starving Ethiopians.

While it is true that Hayes's work is a continuation of the narrative styles developed by artists such as Bosch, Bruegel and Hogarth, he is very much an innovator within that tradition. His figurative style, his use of colour, and the utterly bizarre nature of the narratives contained within each painting, as evinced by their long, rambling titles, these make Hayes one of the very few artists painting today who is extending the realm of narrative art. His paintings are extended visual metaphors for the modern world, with all its fear and loathing.

Polish artist and writer Stanislaw Wickiewicz wrote in 1936 that art had 'prematurely exhausted all its means of producing effects.' He anticipated the demise of art, 'Either by repeating what has already been done or by indulging in total perversity, delirium, and disorganisations of its constructional forms.' If one could spin the contemporary art world around like a globe, at arms' length, one would find it contained large territories that testified to the truth of Wickiewicz's words. How many times can the character of Marcel Duchamp be reinterpreted before the curtain finally falls on the seemingly endless troupe of actors playing his role? One of the most startling examples of this repetition came in the form of Yves Klein's typically Duchampian exhibition of 1958 called, 'The Void.' It consisted of nothing more, and nothing less, than an empty gallery. Proving that even the concept of an empty room can be reinterpreted, Martin Creed earned himself a place in the 2001 Turner Prize final with his piece, 'The Lights Go On and Off,' which was an empty room with a light.

One could also argue that art's structural forms have been partially disorganised, as Wickiewicz predicted, to the extent that language now plays such a dominant formal role in artistic appreciation. In his satirical attack on contemporary art, 'The Painted Word', Tom Wolfe wrote, 'Modern art has become completely literary; the painting and other work exist only to illustrate the text.'

Wickiewicz and Wolfe were both thinking of art in the narrowest sense — that is, art produced by artists who achieve national or international reputations. Hayes thinks the art world cannot be reduced to this level. 'There are artists all over the world producing amazing stuff,' Hayes argues, 'and, for whatever reason, they don't get picked up by anyone with clout in this industry.'

Despite the fact that Hayes's work defies contemporary artistic fashion, where concept is king, and that he still lets his paintings do most of the talking, Hayes was picked up by someone with 'clout in the industry.' Ronald Feldman is perhaps most famous for being the first commercial art dealer in America to lure Joseph Beuys across the pond, and has been a regular exhibitor of Andy Warhol's work since the early 70s.

'Artists like Cameron Hayes only come around every generation or so,' Feldman says, 'I knew that as soon as I saw one of his paintings.'

Of course, art dealers are always going to praise the artists they represent, that's their job — but if you ever get the chance to see one of Hayes's paintings, you might find you agree with Feldman all the same.

Evan Maloney worked as a freelance writer in London for five years, and wrote regularly for Black+White on artists such as Patricia Picininni, Wolfgang Tilmans and Tracy Emin. He's had two plays performed in London and now lives in Poland with his wife and daughter. He teaches literature at an international school.