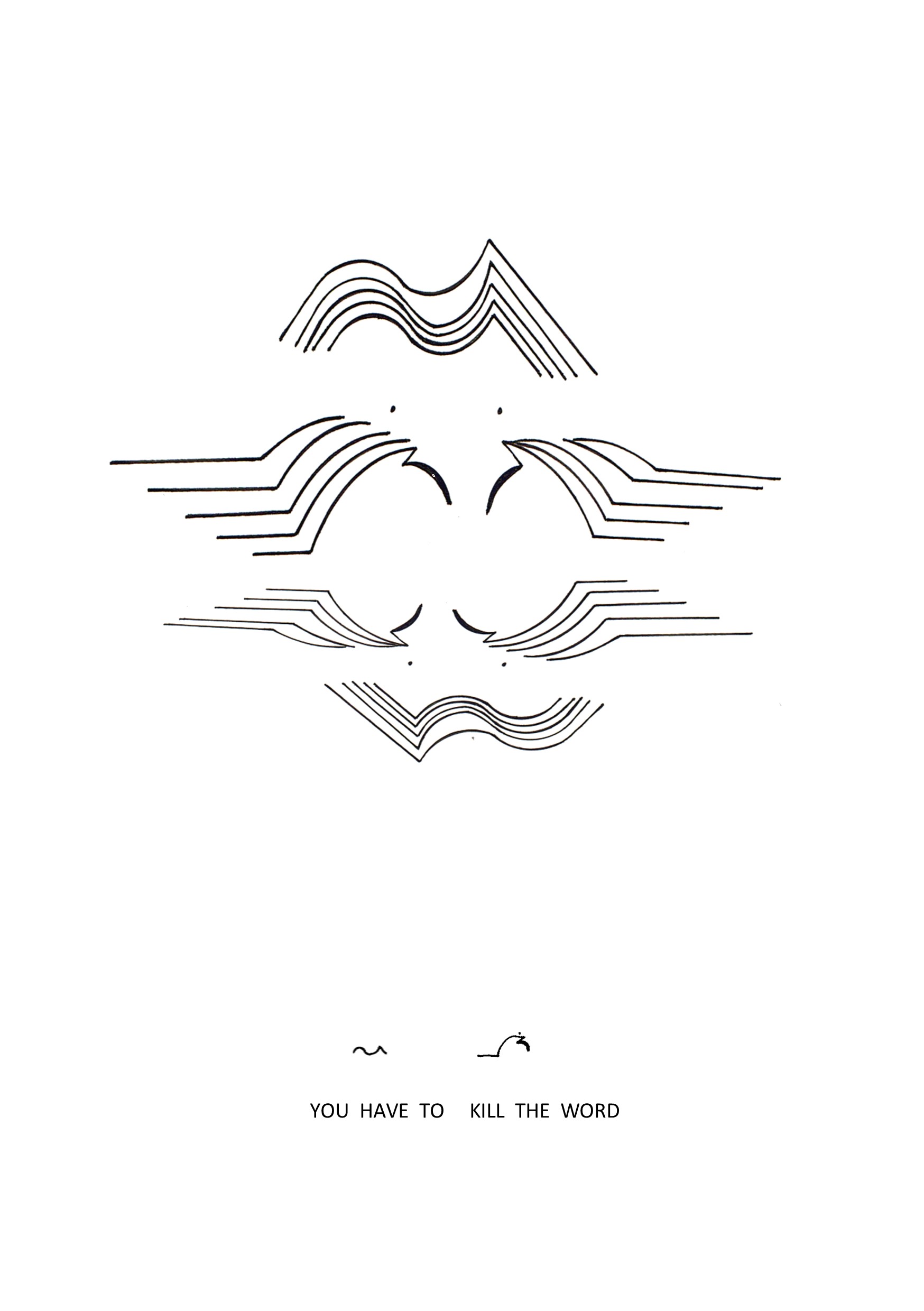

All of these shifts have different interesting impacts on the perception and reading of the poems, as well as showing how they are vividly alive. For thalia, the black and white poems, made with white A4 paper and a black artline pen are the original works and from here she may turn the poem into a painting or graffiti.

The line in thalia’s drawings is always perfectly composed with exacting precision, using rulers and compasses and a steady hand and watchful eye, creating motion, movement and fluidity. In Pitman’s heaviness of stroke indicates consonant sound, and thalia uses this boldness of line to direct the reader’s eye and to create dynamic contrast.

Historically, painting has been known as a ‘spatial’ art, and poetry a ‘temporal’ art, a formal distinction between the art forms that can be traced to Lessing’s Laocoön1, first published in 1766, a long-form aesthetic study that sought to examine the differences between painting and poetry and create a classification system for the arts. Poetry is ultimately seen to be a ‘superior’ form, due to its ability to ‘speak’ and to capture many moments and sentiments, whereas a ‘mute’ picture captures just one scene.

thalia, ‘You Have To Kill The Word, 2001’, pen on paper, 210mm x 297mm

The binary between word and image has a “long ideological history”2 and can be read in gendered terms where “the (mute) image finds itself aligned with femininity, whereas the (explanatory) text is masculine”.3

Visual poetry blurs and collapses these Western traditional classifications on the mutual exclusivity of word and image, and of time and space. Visual poetry is, above all, spatial poetry. And this dimension of space extends not just to the page, but to the books production and to space in a more abstract societal sense, about inventing space for new language.

In a 1994 essay titled The Word Remade, thalia writes “the word, or symbol, or phrase, or any other communicant, is totally dependent on the poet as sole editor and printer of her own work it is the poet who has seized control of the word’s graphic space”.4

It is important to note that thalia makes all her work by hand, whether by drawing, painting, by rolling small balls of blu-tac to affix glass gems to a wall, or by creating her own chapbooks, as we see with the 2005 publication The Culture of Death5, which is an artwork in its format. The textual support of the page and the fold is intrinsic and indissoluble from the content. Each section opens out in a concertina fashion, presenting a triptych of poems, for example, two poems titled ‘Intelligence Information’, open onto ‘Of Mass Weapons Destruction’. Other poems in the series are titled ‘Nationalism’, ‘Occupation’, ‘Massacre’, ‘Carnage’. Responding to the Iraq war, the continued resonance of this work is a reminder of a permanent state of warfare. thalia’a self-made chapbook The Culture of Death is one of her most powerful works, and also as an example of reportage. While thalia worked as a typist and secretary, and not as a journalist, her engaged poetry responds ceaselessly to contemporary events and concerns. For the last two years, thalia, has been responding to and documenting the siege and genocide in Gaza, six poems of which were published in a recent issue of Collective Effort’s literary magazine Unusual Work6 (itself an enduring magazine, with 40 issues published over the last 20 years). In this series, the figure of massacre returns.

The understanding that the poet is the creator and disseminator of her own work provides thalia with the freedom to create her own visual language and create her own poetics, with a distinct pictorial structure and syntax. This hinges imperatively on space, on rejecting the normative linearity of typical written poetry and relies upon rejecting the fast news and dictation speed of shorthand. Through her shorthand poetics, the world flows through her, thalia documents and translates the world and language around her, composing her own pictorial-poetic reportage into timeless distilled polysemic images.

- Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim. Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984. ↩

- Steiner, Wendy. ‘Introduction’. Art and Literature, Poetics Today 10, no. 1 (1989): 1–3. ↩

- Louvel, Liliane. The Pictorial Third: An Essay into Intermedial Criticism. Edited and translated by Angeliki Tseti. Routledge, 2018. ↩

- thalia. The Word Remade, The Guide, August 1994. ↩

- thalia. The Culture of Death. Ocean St. Production, 2005. ↩

- thalia. ‘Rage’. Unusual Work, no. 39. Collective Effort Press, 2025.

thalia. ‘Ethnic Cleansing’. Unusual Work, no. 39. Collective Effort Press, 2025.

thalia. ‘Banks Tanks’. Unusual Work, no. 39. Collective Effort Press, 2025.

thalia. ‘Fear’. Unusual Work, no. 39. Collective Effort Press, 2025.

thalia. ‘Besiege’. Unusual Work, no. 39, Collective Effort Press, 2025.

thalia. ‘Of Lies/Laws & War ‘. Unusual Work, no. 39. Collective Effort Press, 2025. ↩