In the early 1970s when thalia was learning shorthand (and Business schools offering shorthand were still proliferating), the international concrete poetry movement, a movement instigated and established by the Brazilian Noigandres Group in the mid to late 1950s, was continuing to globally pick up momentum. On a local level, thalia was involved in the poetry scene in Melbourne, where she describes how between 20–25 poets would regularly meet at each other’s houses, sharing work and ideas, and how sometimes one of them would publish a collection of their work or have a poetry show at Strines Gallery, run by Sweeney Reed1. Magazines and publications also grew from these gatherings, such as Born to Concrete (1973–1976)2.

The Brazilian concrete poets in their initial manifesto ‘Pilot Plan for Concrete Poetry’3 attest to “Graphic space as structuring agent” and exploited this dimension of the page, combining and critically responding to current developments in graphic design and advertising, as well as in architecture and poetry. Concrete poetry focuses on a reduction of language to the material dimension, breaking down the word, the letter form, and the sound. And one of the ambitions of the concrete poetry movement was to form a new mode of communication — a universal language — that transcended linguistic barriers and stressed the ideogram as an object that represents an idea through a concise image.

Pierre Garnier, who alongside Ilse Garnier founded the movement Spatialisme in the 1960s, describes how “with concrete poetry we have succeeded in making a poem from just a few words that remain in oscillation because of the arising relationships. Here, the togetherness (or opposition) of image and word, the image-word constellation, kindles the poetic spark.”4 The generation and the potentialities of this third space, the poetic spark, through the oscillation of image and word, emerges, again and again, in thalia’s visual poetry.

The symbols of shorthand have proven to be a highly generative constraint for thalia. Reading her visual poems, the eye actively darts over the page, flitting between the hand drawn arrangement in the centre, and the gloss or legend at the bottom, which presents symbols from Pittman’s inscription alongside a translation. There is a triangulation of these three elements: image, notation, and translation. These are productive gaps and third spaces that emerge: between the word or phrase and the pictorial representation, and between the English translation and the shorthand notation, presenting both visual and syntactical disruptions and inventions.

There are four primary visual compositional structures, or compositionals, that emerge in thalia’s poetics, and which sometimes blur and combine in a single poem.

1) Poems constructed through the repetition of one image as a discrete entity

thalia, ‘Collective’, 1979, pen on paper, 210mm x 297 mm

This can be seen in ‘Collective’, composed of the notation for individual and resembling birds flying in a flock. It is important to note that for readers of shorthand these poems are completely legible, and thalia sometimes leaves some coded messages in the poems for shorthand readers only, as can be seen here where one of the individuals in the flock is an individualist.

This compositional can also be seen in poems such as ‘First Daffodils’, where the symbols for ‘daffodils’ and ‘first’ combine to represent the icon of a flower, creating a cluster of daffodils on the page, and in the poem ‘Army’ which repeats the symbol for ‘nincompoop’ in phalanx formation.

2) The repetition of a shorthand symbol to construct an iconic picture or geometric shape

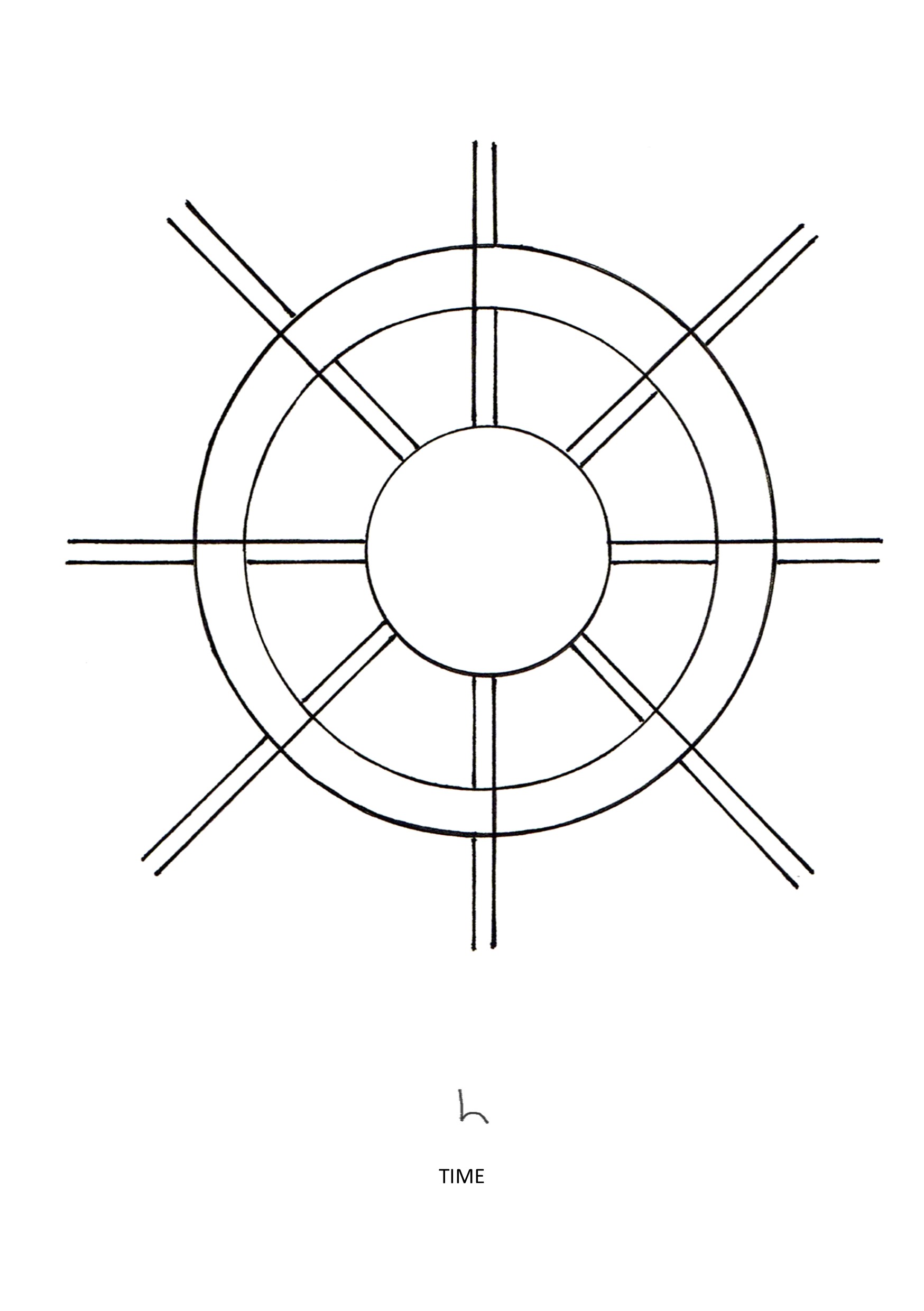

thalia, ‘Time’, 2004, pen on paper, 210mm x 297mm

This compositional can be seen in many of thalia’s concrete poems including ‘Time’ which takes the iconic shape of a ship’s wheel, and similarly seen in ‘Detention’, a poem resembling curls of barbed wire, constructed out of the repeated notation for ‘boundary’.

thalia describes how in her poetics she, “turns the written word of language inside out, upside down”.5 Such a statement isn’t just figurative. Mirroring, repetition, symmetry and inverse lettering and the manipulation of geometric space are core to the visual and syntactical disruptions which characterise her practice.

3) The construction of a non-mimetic, abstract assemblage

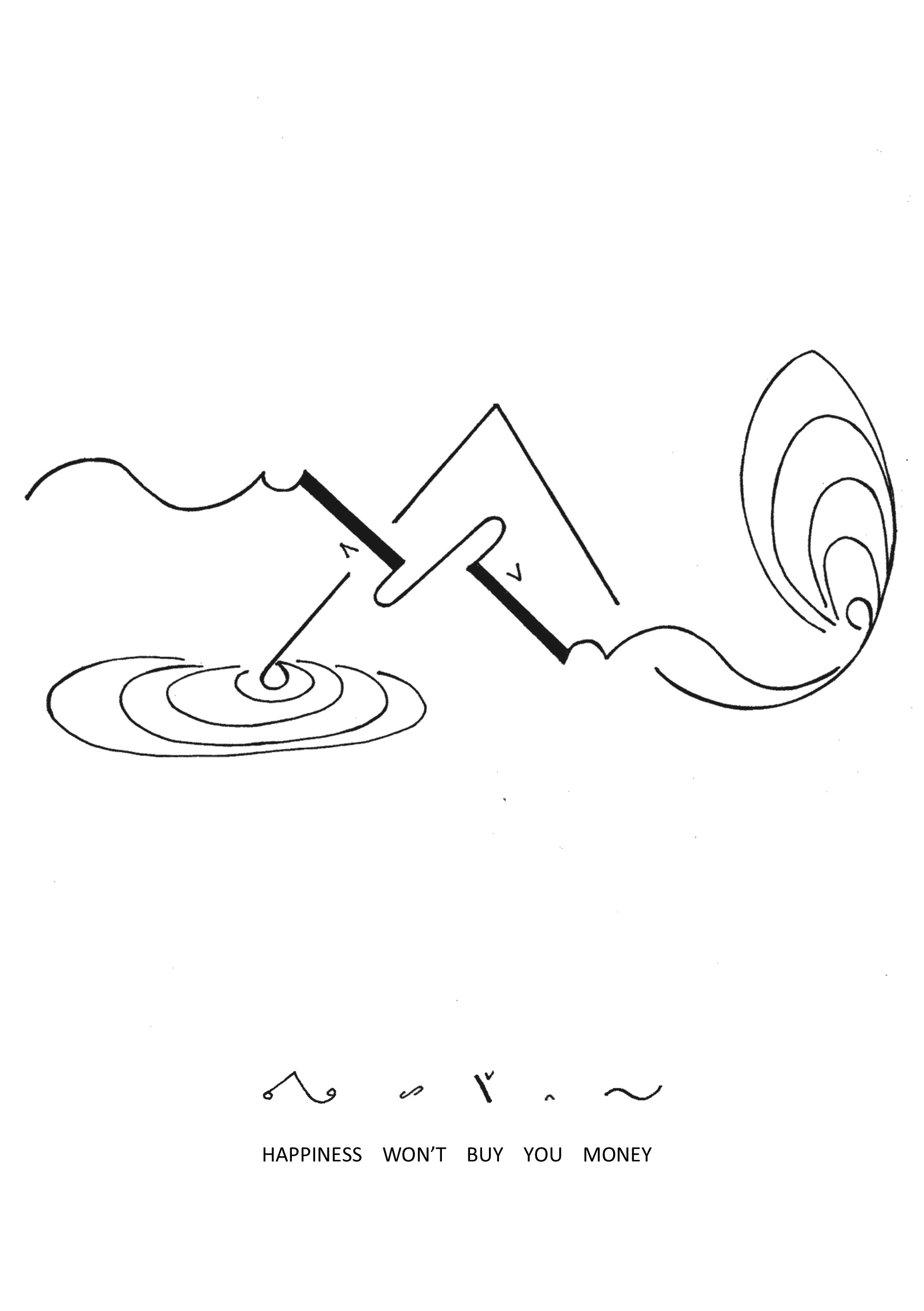

thalia, ‘Happiness Won’t Buy You Money’, 2001, pen on paper, 210mm x 297mm

Sometimes what is represented in these works is an abstract construction, operating on an unconscious level, on the level of a polysemic image. Reader-viewers are given the puzzle of the poem, with new associations and understandings often unfolding. Yet in their abstraction, repetition and rhythm, the dynamic energy and interplay between the graphic poem and the textual notation creates an energetic dynamic that seeks the reader-viewers participation to actively construct meaning. Such a composition can be seen in ‘Becoming Aware’ and in ‘Happiness Can’t Buy You Money’, a line borrowed from Jas H Duke.

4) The creation of isomorphic figure(s) through the loops of shorthand

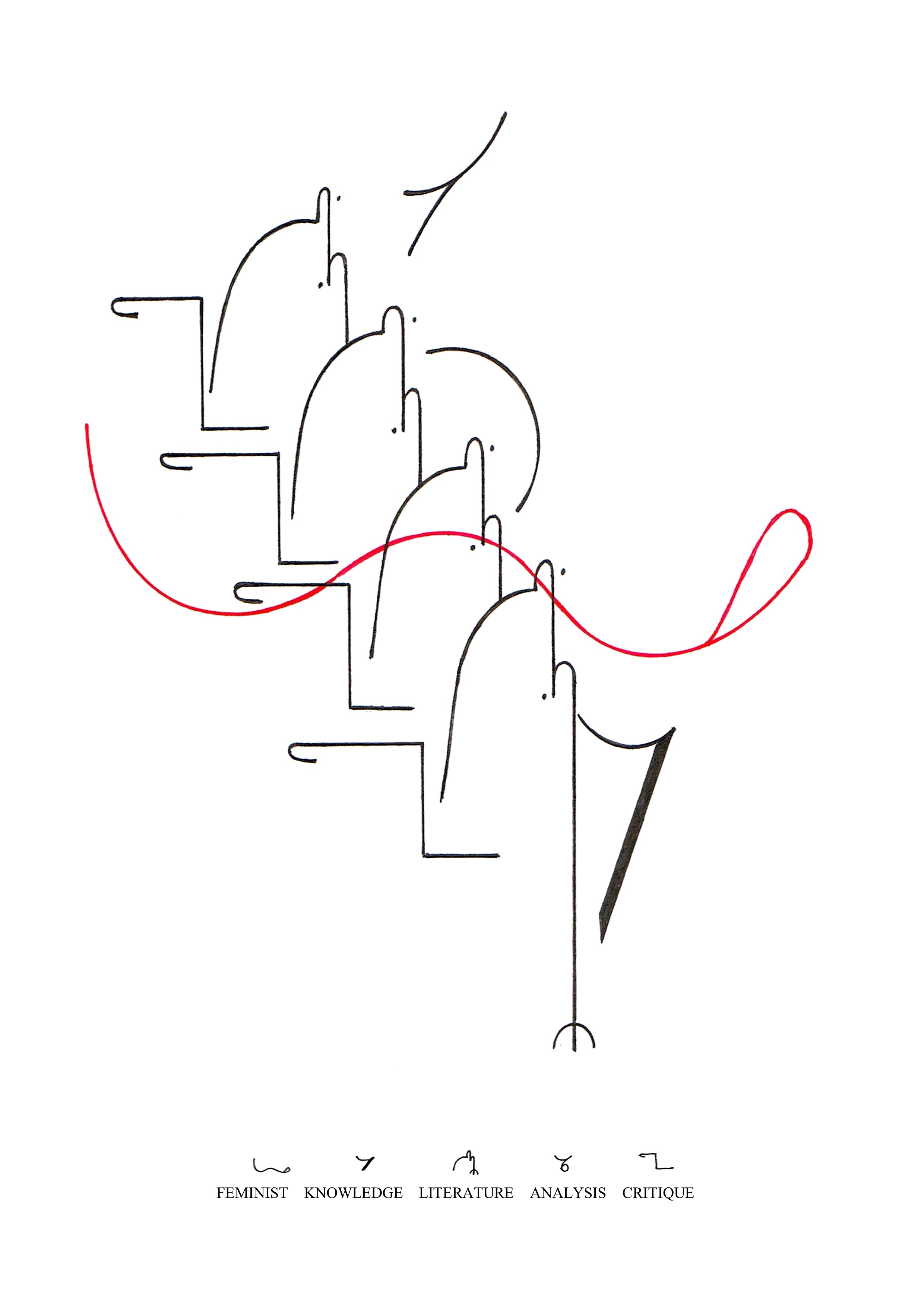

thalia, ‘Feminist Knowledge Literature Analysis Critique’, 1986, pen on paper, 210mm x 297mm

The human face and figure recur in thalia’s poems, as do the shapes of animals as can be seen for example with two rearing horses in ‘Social Problems Unite’, as well as in the poem ‘Feminist Knowledge Literature Analysis Critique’, where four dolphins represent literature.

thalia’s poems are never static – she animates the word, working with the associative polysemic image and the dynamic interplay of image, text and sound. They are also never static as often poems will repeat, with the same gloss but with a shifted poem, or in a sequence where a pattern is doubled or multiplied, and also through intermedial interart transposition.

- thalia, A Brief Summary of Concrete and Visual Poetry in Australia as of the 1960s, 2003 ↩

- Born to Concrete was Australia’s first magazine dedicated to concrete poetry and ran for four issues. ↩

- de Campos, Augusto and Haroldo, and Pignatari, Décio. ‘Pilot Plan for Concrete Poetry’. In Concrete Poetry: A World View, edited by Mary Ellen Solt. Hispanic Arts, Indiana University, 1968; Indiana University Press, 1970. This manifesto was originally published in noigrandes 4: poesia concreta (1958) and was republished in Solt’s anthology, translated by the authors. ↩

- Garnier, Pierre. ‘Constructivist Poems’. In Experimental – Visual – Concrete: Avant-Garde Poetry since the 1960s, edited by Johanna Drucker, David K. Jackson, Eric Vos, translated by Eric Vos. Rodopi, 1996. ↩

- thalia. The Word Remade, The Guide, August 1994. ↩