This essay on the poet thalia was adapted from a talk presented at the symposium Enduring Experimental Poets held at East Melbourne Library on 22 October 2025, alongside papers on Javant Biarujia (by Brendan Casey) and Catherine Vidler (by aj carruthers). The symposium was programmed by Victoria Perin and presented by un Projects together with the Melbourne School of Literature.

thalia is one of Australia’s foremost visual poets, with an expanded poetry practice spanning from 1972 to the present day, working across writing, drawing, painting, rhinestones, embroidery, and, occasionally, sculptural glass beads affixed to garden walls and fences as graffiti. thalia’s enduring body of work is summarised in her major publication A Loose Thread, published by Collective Effort Press in 2015, which collects over 180 of her visual poems. She herself is a foundational part of Collective Effort: the renowned and enduring Naarm-based poetry collective that includes notables such as π.o., artist, sculpture and poet Sandy Caldow, Dadaist Jas H. Duke and poet and editor Jeljte, among others. thalia is a poet of the people; as well as having her poetry exhibited and published globally (for example, at the 1990 International Exhibition of Concrete Poetry held in Moscow) she often presents folders of her poetry at provincial towns and folk festivals around Australia with her partner, folk musician Alan Musgrove, whom she has collaborated with on an album of poetry, songs and music, Interplay1. thalia was a founding member of the Australian Poets Union and a co-founder and editor of the worker’s poetry journal 925, a little mag which ran from 1978 to 1983.

A singular and iconoclastic poet, thalia has developed an original, striking symbolic visual language through a practice of visual poetry constructed with the abbreviated writing system of Pitman shorthand, which relies on phonetic orthography — a practice known as phonography (Greek for sound writing). thalia has also called the method “soundhand writing”2, no doubt after Pitman’s first treatise on shorthand, Stenographic Sound-Hand (1837)3 that was initially learnt and deployed by scribes and reporters. Post-1914 (WWI), women were employed and took over men’s work and a predominately female workforce of secretaries and typists ensued.

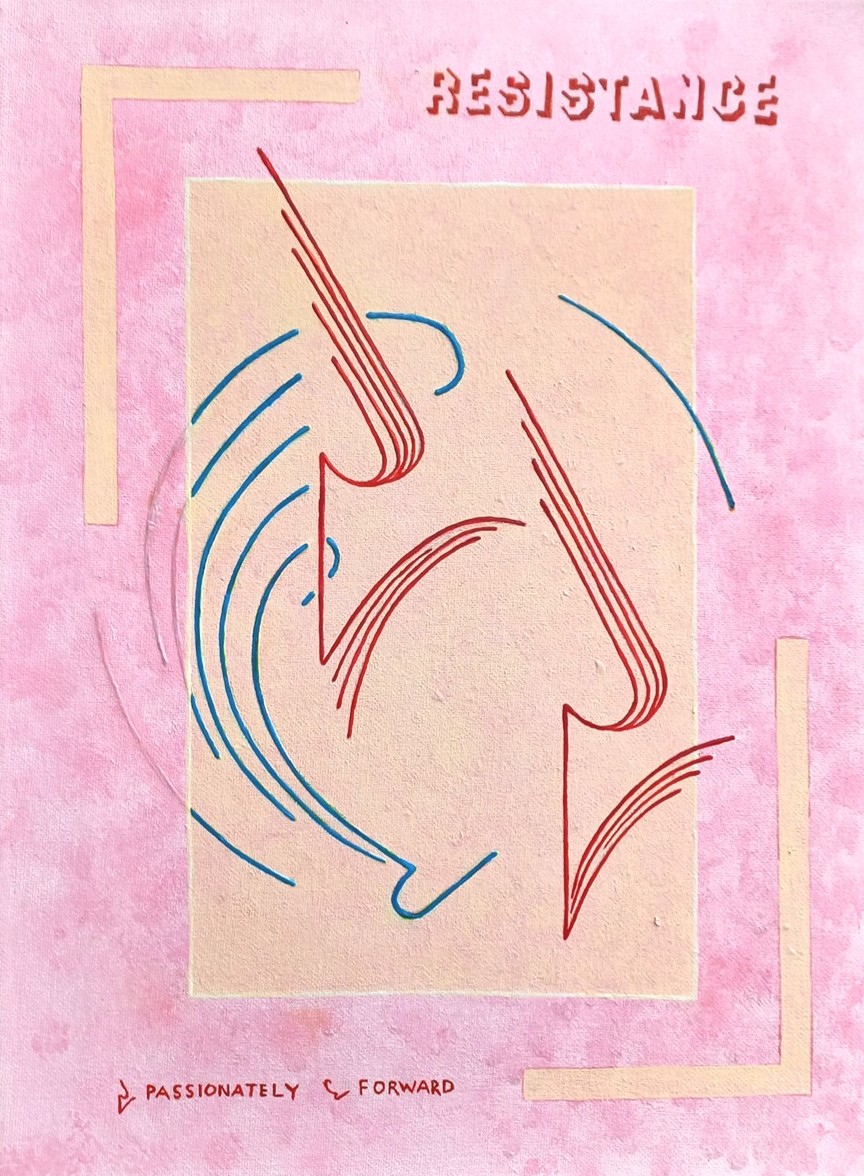

In both form and theme, thalia’s visual poetics poses a counter-position to the Western supremacy of the written word, and to dominant entwined power structures of imperialism and colonialism. Hers is a fiercely feminist, leftist poetics that is embodied by the form of visual poetry that merges processes of reading and seeing, challenging hierarchies, binaries, and ideas of composition (both in text and visual art). While Pitman shorthand is designed to be written on lined paper, thalia composes her poems on blank sheets, enlarging the symbols and removing Pitman’s horizontal line used to demarcate vowel sounds. thalia’s words come towards you, as much as they flow from left to right. They remember — but more or less abolish — linear reading, as can be seen in the dynamic circular form of “passionately forward”.

thalia, ‘Resistance’, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 40 cm

Born in Greece in 1952, thalia emigrated with her family to Melbourne in 1954, aged two. She grew up in Fitzroy, alongside her brother π.o., and left school at the age of 14 to help her mother, who was chronically unwell, in her shop in Fitzroy. At the age of 20, thalia learnt shorthand, taking intensive classes for the duration of a year. When thalia was learning and working with Pitman’s, she saw pictures and thought, ‘This is poetry.’4

She writes that in making use of Pitman’s, she achieves several things:

1) Honours countless generations who have had to write in code 2) Dispenses with the dominant written language, and thus creates a new written word, one which is/was primarily a women's domain 3) Transforms a worker's tool into art.5

These three aims have remained pivotal to her practice.

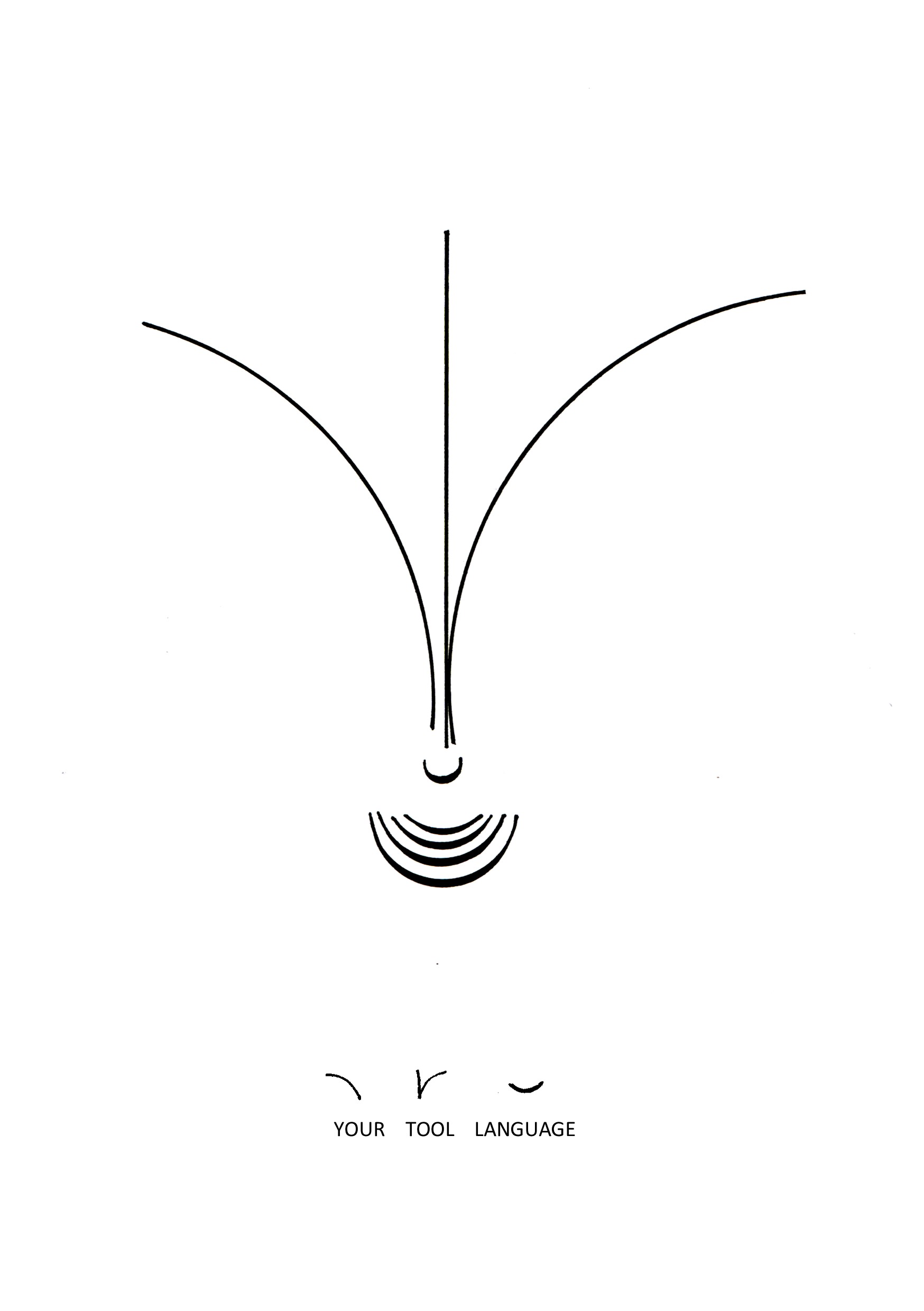

Rather than using Pitman’s as a code for writing texts, thalia creates new images from the notation and provides readers with a key of the shorthand notation. Decipherment is incorporated into the reading frame, moving between codes and languages. In thalia’s poetics, the hand-drawn image and words merge and become one, presenting a sonic, textual and visual fusion. Sometimes mimetic, where the image and the word express the same subject, there is also often disjunct or a puzzle between the visual and the verbal. The picture-poem presents new interpretations of the word and world, and a doubling that recalls an optical illusion, where the eye zooms in and out, as can be seen in ‘Your Tool Language’.

thalia, ‘Your Tool Language’, 1986, pen on paper, 210mm x 297 mm

If we are to read the poem following the notation, we read, “your tool language, language, language, language”, while the eye moves between the images we are presented with: a pen nib, a clit, a face. Language is presented as limitless and at our disposal, and there is a reversal too, away from a patriarchal language, where the pen is a phallic symbol.

- Musgrove, Alan, and thalia. Interplay. Collective Effort Recording, 1996. CD. ↩

- thalia. The Word Remade, The Guide, Queensland Poets’ Association, August 1994. ↩

- Sir Isaac Pitman’s initial 12-page pamphlet Stenographic Sound-Hand was published in London by Samuel Bagster in 1837. ↩

- Spoken to me in conversation, October 2024. ↩

- thalia, Visual Poetry: Reading the Image. ↩