Region is not acknowledged in contemporary Australian poetry – which is strange since the way we see our tradition is in terms of bush and country. It's also what most contemporary poets have rejected in fact (and, legitimately, act in opposition to). What is now forming is an urban/suburban/rural split. Les Murray remarks on this often – the title of his recent collection Subhuman redneck poems is itself a direct challenge. This is how Murray thinks some suburbanites see non-urban people. If the country is seen as wildly exotic, how, then, is poetry of the Northern Territory seen? Or not seen?

For the Northern Territory, it's much worse than someone like Murray suspects. Many Northern Territory poets feel invisible and possibly unwanted. If there's a view of the NT at all, it's a tourist brochure. The more alert might have political views, but most outsiders see the Northern Territory as a vaguely exotic hot dry outback version of south-eastern Australia. They would be shocked if they knew how wrong they were. There are many Northern Territorys – not all of them rural, not all of them coastal, or inland, or sophisticated or grass roots. In any case it is not the urban and southern, cultures which dominate elsewhere.

This gives rise to problems for Northern Territory writers; if their culture(s) are not recognised as 'Culture' their writers are put into the position of constantly writing in reference to what they are not; or of writing out of strong and legitimate sense of place, region and identity, which is almost certain to be misread.

This is a problem for genuinely regional writers everywhere. Writers not from the metropolitan areas are not even very fussed with the term 'regional' ('region' ha!. . . as if Sydney, Melbourne or Brisbane were not themselves regions. . . the term really means 'not us' and it would be useful if this hidden attitude was brought out into the sunlight and examined). Regionality is, at best, only nodded to in Australia. At best it's a 'we're all equal' (to me)(though you're invisible) policy – at worst it's 'urban poetry is real poetry' and dilettantes live elsewhere.

Northern Territory writers know the way they look at the world is different to the way the rest of Australia looks at the world. In the words of one of the territory's writer 'I've been all over the world but I never felt so foreign as when I went out to teach in a remote area school in my own country.' This is the discovery that 'your own country' is not your own country at all – that it is different and more alien than anything you had previously dreamt of.

If you're defining your culture in terms of another culture, you will, by the foreign culture's light, always fail. In similar situations, others have learnt to write in a double voice – in the mainstream market. Think of women writers, think of Julia Leigh's new novel The Hunter – extraordinary in that it seems so very male. There is the temptation for Northern Territory writers to do the same. No one wants to fail, to be misread.

However Northern Territory poetry doesn't fail. It sounds different up there. There is a different sensibility about place, voice, dispossession and relation to the world. Much of Northern Territory's poetry is not written down – never makes it to the page.

Most people think of Northern Territory poets, if they think of them at all, as more or less the same as anywhere else – the same but with local colour. It's not so much that the differences are reflected in the subject matter (though it is that too) but in the rhythms of the works. In this sense, it's more like American poetry than it is like southern Australian poetry.

Belonging to the Territory is a qualitatively different thing altogether – and it's not just black and white.There are many Northern Territorys, and the mix of races and cultures which much of the time live with one another on a daily basis and this informs the writing.

Val O'Neill, like many Northern Territory poets, confronts race issues – black, white and landownership issues – head on. Few in the south would feel themselves entitled to do it. The short lines that she and Jackie Swift use have a slowing effect. The story-telling is elliptical – not the gallop of a Fredy Neptune, where the events drag us through page after page, or the staccato images and references of, say, Gig Ryan.

Landscape, as seen in Northern Territory poetry, says much about relationships and attitudes. Landscapes elsewhere are often small-scale, domestic, close-up and personal – as enervating as that is. When you're in the Territory, listening to the speech and references – even for a little while – you realise that the tone, rhythms and imagery in the poems are not incidental. Are not 'local colour'.

There's a different sense of time and this is reflected in the rhythms and subject matter, and in the underlying humour. Sometimes this can sound curiously flat to outsiders. . . just as, say, some Americans can seem tediously conversational to an Australian ear. I'm thinking of Michael Watts' sardonic humour in his 'The River': 'As the MacDonnel Ranges sit and wait | For this town to blow away'. A couple of lines, with a slow smile, but you need to have been there and to have seen the MacDonnel Ranges, and know that they are the most ancient and unearthly-looking bunch of dinosaur vertebrae – and near bare of vegetation. You've got to know the river – and not from television, but to know the culture of the riverbed and what it means. If you don't understand Northern Territory poetry and think maybe this image or that image is bit light on, you might have to consider what you don't know about the Territory.

Kaye Aldenhoven's 'Pandanus Fruit – Ubirr' is a poem from another culture. To fully appreciate the poem, you need to share the knowledge of the fruit and the place Ubirr. It's not that she needs to say more – it's common knowledge in the Territory. . . and if, as Hugh Tolhurst suggests (see Cordite #4 and #5), it's sheer ignorance which makes us bad readers, then Territory writers have been very patient. I wonder if Northern Territory writers have forgotten that the rest of us don't know what they know when we read what they write.

Northern Territory people know different things to the rest of us and look at things more circumspectly – this compares to the direct gaze of the urban writer (notwithstanding the ironic 'no comment' of even the most hyperpomo-cover-my-tracks poet).

What impresses me, even with the poems which end with a joke or a throw-away line, is that there is a seriousness of purpose. Not self-regarding particularly. Sometimes when you read urban poetry. . . it is as if poets have run out of things to write about. . . and they start on the alphabet poems, or poems on the days of the week, or translations, or descend into that irritable cleverness which is all wit and no witness. Bored poems. There are bored poems everywhere, and some of them are good, some of them amusing, some of them written by some very good poets which is fine, but not if they become the dominant poetic culture of a place to the exclusion of all else.

Issues of judgment and rights are bought up every day in one way or another in the Territory. The mad Northern Territory laws which lead to mandatory imprisonment for even a young mother over a minor disagreement in a shop (to the chagrin of the shop owner as well as to the 'criminal'), the dodgy deals done over land, the uranium protesters. . . This issues are larger and more real than most urban issues – and frequently appear in the poetry of the Territory.

Some Northern Territory poets don't write in English and that's when you know you are living in a different country. Compare how Michael Watts writes when he's speaking about the Territory and how he's writing when he speaks about 'Those Blue Mountains'.

While poets everywhere are struggling financially, poetry is alive and well in strange places. Poetry itself has freedoms because it's seen to be a harmless pursuit, eccentric and economically uninfluential. Its marginalisation means that it can do what it likes and no-one will complain, except perhaps poets themselves. . . and usually about themselves, the way they are treated, who thought what of their latest book. Northern Territory poetry suffers and delights in a further marginalisation. . . it's seen as outside the main thrust of Australian poetry. . . if it's seen at all.

There have been many policies designed to thwart this last perception at both an institutional and at a personal level, but this is useless unless we look for and acknowledge differences – and encourage them. The Northern Territory literary poetry prizes are now restricted to Northern Territory writers only (although I believe this is currently under review) which further removes an arena for Northern Territory writer to participate in Australian Literature. I can imagine the reasoning behind it, but it effectively tells Australian writers, and Northern Territory writers in particular that they are not fit to compete on a national stage.

There are currently a limited number of forums for Northern Territory writers to see themselves as Northern Territory writer. Now that the Northern Territory Writer's Centre is up and operational, and with a proactive executive officer in Marian Devitt, there is more cross-fertilisation. However, with the journal Northern Perspective offering no, or highly irregular, perspectives on issues, Northern Territory writers have limited opportunities to examine their own particular cultures and have to speak in (literally) foreign tongues.

Northern Territory is not another state of poetry, it's another country – the difference hard to define yet understood by most poets who live there. It's got enough critical mass perhaps to have a community of poets and is marginalised enough to have a liberty to write what and however it wants. It's hard to pin down and hard to even say that there is one Northern Territory. There is huge diversity of experience and location and it is struggling, and winning, a place in Australian poetry. I hope. The more Northern Territory poetry defines itself as the centre of the universe the stronger it will become.

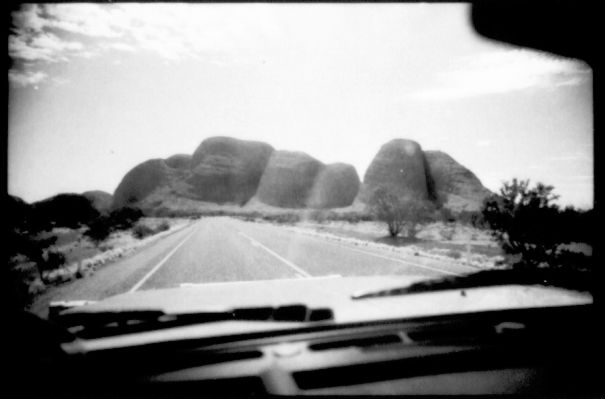

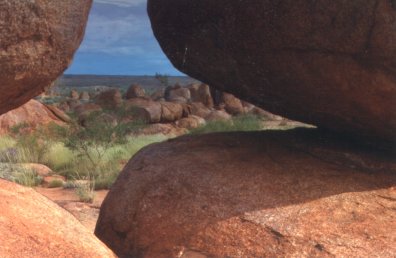

Images: Adrian Wiggins 'Approaching Kata Tjuta in a Ford Maverick' (top); Coral Hull 'Inland' (bottom).