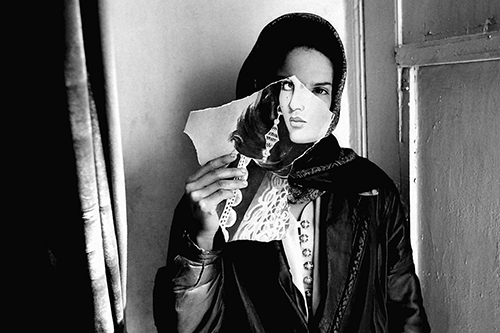

Afghani poet Nadia Anjuman (1980—2005) grew up among a small literary community that encouraged her writing even during Taliban times. She was one of the first women to enrol in Herat University after the fall of the Taliban, but her pursuit of a literature degree was cut short when she was killed in an incident of domestic violence on 4 November, 2005, just short of her twenty-fifth birthday. Her chosen pen name honours her beloved Herat Literary Society, Anjuman-e Adabīye Herat.

Nadia Anjuman wrote many of her poems in traditional Persian forms such as the ghazal, a poem made up of five to fifteen grammatically independent couplets, utilising a refrain and rhyming pattern directly preceding the refrain. In Persian (as well as other languages like Arabic, Urdu, and Turkish) the form adheres to a strict metrical pattern and usually addresses themes like love, longing, and existential questions. Herat’s literary community considered Nadia to be one of the most skilled young poets of her generation, especially when it came to classical forms like the ghazal. One of the challenges of translating formal verse like Nadia’s is the question of how to preserve or recreate these forms in the English language (or, indeed, whether one should attempt to do so at all). Does a formal approach to translation facilitate the reader’s access to the sounds and rhythms of the original piece, or does it run the risk of polluting meaning by attempting to fit ideas into forms that work very differently in the destination language?

The poem Abas (Makes No Sense) is known to many Afghans by the name Dūkht-e Afghān (Afghan Girl), which is a song by musician Shahla Zaland that uses Nadia’s poem as lyrics. In translation, I have loosely aligned this poem to the ghazal-form in English.

The two poems included here are found in Anjuman’s 2005 collection Smoke-Bloom.

Pingback: Learn English through short stories – Nadia Anjuman | Chatsifieds.com