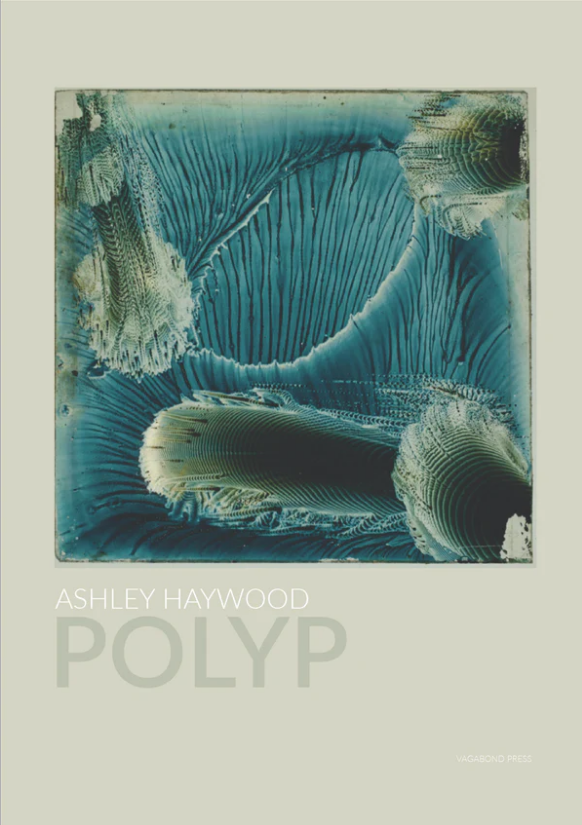

Polyp by Ashley Haywood

Polyp by Ashley Haywood

Vagabond Press, 2024

Islands by Brett Cross

Vagabond Press, 2024

Clustering is a technique for mind-mapping the parts of any whole. Organisms cluster into ecologies, people cluster into communities, and poems cluster into collections. In Polyp and Islands, clusters of cells, beings, and places form and dissolve. Both books explore the flux between separateness and wholeness in nature, each word and line branching into vaster topographies. The poems arrange in organic patterns, then undermine their own classification by splitting, mixing, and rejoining themselves in new arrangements. Following suit, my review clusters Ashley Haywood’s and Brett Cross’ interpretations of the more-than-human world.

Themes of time and change propel both collections. Both engage with global ecopoetry by presenting Antipodean places as simultaneously physical and psychological. Both pose questions of human versus non-human voice and, in doing so, expose the smallness of personal perspectives. Both are marine inspired, their lifeforms springing from and returning to deep-time oceans. But the poets’ approaches differ: Haywood is scientific; Cross, humanistic. Haywood relates human to non-human cultures while Cross relates human cultures to place. I see Polyp as more innovative, Islands as more resolved, and both as strategically brilliant. Haywood’s poems are interlinked cells coalescing into organisms; Cross’ are layered sequences crystalising into islands.

In Polyp, Haywood, a transpersonal art therapist with a background in biology, investigates sentience by fractalising the voices of corals and humans. Shortlisted for the 2025 Mary Gilmore Award, Polyp’s sixty-three-page scope stretches from the microscopic to the mythical. Its coral and human voices strike strange, experimental harmonies in a concurrent language of part and whole. To read Polyp is to share the consciousness of primordial marine beings threatened by environmental disaster. I reread this collection several times, dipping in at random for poetic microdoses that echo the macro in mind-expanding ways.

Polyp was inspired by twentieth-century coral expert Dorothy Hill’s writings, “ninety-four boxes of collected personal and professional papers, including handwritten drafts of scientific papers and hand-drawn maps, correspondence and photographs, reports and fossil illustrations” (‘Notes,’ 62), which Haywood studied at the University of Queensland. The final poem characterises Hill’s work as a “Glass Slide […] / Lost to time” (‘Glass Slide; or, As I lay down in the instant,’ 58), and Polyp’s sparse pages also resemble smeared slides. Haywood examines ecological grief and hope with scientific tenderness, predicting, “[One hundred million years from now ] / The plastic stratum is the colour Goodbye” (‘Domestic Spill (5),’ 43).

The first poem, ‘Ars polyp,’ maps out Haywood’s cross-disciplinary premise in sections labelled “BIOLOGY,” “MEDICINE,” “POESIS,” and finally:

LITERARY Poem with one or many

tentacular mouths rising to meet

my under-image.

(9)

These lines respond to a Beverly Farmer quote, “Let go and rise up into your mirror image, your hands, yourself, your underimage” (This Water: Five Tales qtd. in ‘Notes,’ 60). Haywood’s core task, then, is to investigate the embodied self as reflected by other lifeforms. The human voice is concurrent with myriad non-human voices, all equal tools for calling out climate issues, specifically coral reef bleaching events. As Polyp proceeds to enact this multi-self-reflection in mirrored water, sentience becomes a collective rather than individual reality.

Unembellished sketches swell with repeated mouth and tongue images that reinforce Haywood’s emphasis on voice. Some poems are freestanding clusters, such as ‘Rockpool’ (41), but most interlink as a broad ecology. Preoccupation with whole and part manifests in intricate arrangements of cells. Folds and mouths represent not only more-than-human voices, but also geological strata that lead to the depths of creation and extinction: “What is in your mouths? Gaping / parched clay slabs layered like accidents” (‘Portraits,’ 47).

To capture the rhythms of voice, Haywood mixes visual patterns with assonance, consonance, and onomatopoeia:

Root-

held

dune, skin like

wind-

swept

jelly-

fish—

(‘Small Dance,’ 55)

While voice is prominent, identity is even more in question, with phrases like “whose / hand, foot?” and “[who in the]” repeated throughout (‘Small Dance,’ 55; ‘On a long walk away from away and waking with the sun,’ 57). Beneath Haywood’s focus on voice and identity lies the conundrum of non-human consciousness, and beneath that, a nihilistic solidarity with threatened lifeforms. The pronouns ‘you’ and ‘I’ are scattered interchangeably so that the reader questions not only who is speaking, but individuality itself. There is no discernible distinction between human and non-human voices; instead, “you and me we // loop” (‘Domestic Spill (6),’ 56). This relational ‘loop’ is biologically and metaphorically generative, smacking equally of extinctions, recycling symbols, digital webs, and geological ages. The word ‘polyp,’ too, is rich with associations (a slippery, alien shape in some deep-sea intestine), and Heywood conveys all this amorphousness in startlingly simple language.

Body-mind metaphors are seamlessly integrated, for instance, “you see!— / you were always mostly empty space” fuses a physical with a metaphysical recognition of anthropocentrism (‘Portraits,’ 49). Haywood explores complex theories of more-than-human co-creation, but her touch is light. One endangered species addresses another, ironising human rhetoric: “If I’m a failed sestina, what poem / are you? Words” (‘Domestic Spill (2),’ 27). Destructive and commonplace pastoral practices prompt only lassitude:

I lay awake in the company of lambs

engineered to say nothing

forget.

I’ll be gone by morning.

(50)

Polyp clusters biological with mythological stories, describing both as “heir- // loom” inheritances (‘Waterborne,’ 51). Compound meanings amass behind succinct lines: “Let me tell it this way, the way / a quiet seed is ritual / in folds” (51). References to classical mythology accentuate the relationship between Western anthropocentrism and environmental destruction. The concentration of mythical references toward the end of the book suggests humanity’s demise and eventual reduction to an historical myth.

In six ‘Domestic Spill’ poems, Haywood interrogates everyday wastage. Full of ambiguous “you, me” idioms (‘Domestic Spill (4),’ 40), these poems feature plastic debris, weeds, and cigarettes, drawing familiar links between industry and environment. ‘Domestic Spill (1)’ begins: “I am poem parts, dumped end-words / left on the sidewalk for the passer-by” (20). The ‘Domestic Spill’ poems act as anchor points for interspersing pollution events across the book, while simultaneously ‘spilling’ into universal realms beyond mundane experience (20; 27; 32; 40; 43; 56).

The genius of Polyp lies in its embodied merging of human and non-human. Motifs of coral and human mouths and tongues emphasise speech, consumption, and story, then expand into structures of sex, birth, and death:

circling the lips of

old graves fertile tussock

mounds

(‘On a long walk away from away and waking with the sun,’ 57)

Places and times cluster together in a further, planetary perspective: “On the atlas, we” take “micro- // cosmic steps” (‘Small Dance,’ 55). Humans, corals, and other lifeforms are ephemeral blips on the map as a “frond folds wetly / already now / already earth’s understory” (‘Understory,’ 53). A dual “sense of living in two distinctly different temporalities at the same time” parallels Polyp’s mirrored water metaphor (‘Notes,’ 61). In ‘Shadowtime in the Eromanga Sea,’ this altered reality is not only multitemporal, but also multisensory: “I can hear [I can hear] // The distant taste of salt” (23).

Polyp’s final lines are “I can hear fish among fish / sing at dawn” (‘Glass Slide; or, As I lay down in the instant,’ 58). Is the ‘I’ coral, human, or both? Who are the ‘fish among fish,’ and is the ‘dawn’ past, present, or future? Do these questions even matter when all species are eventually replaced? We eat and are eaten by, speak and are spoken by, other organisms. This final enigma clinches Polyp’s epigraph by Clarice Lispector, which foreshadowed ego death from the start: “‘I’ is merely one of the world’s instantaneous spasms.”

Biological and philosophical thinkers will enjoy this book. So much of science informs ecopoetry and Polyp stands out for its multimodal clarity. The strange becomes familiar as Haywood observes life and death unfolding. Ecologies are collective places in which creation and destruction co-occur, as the last poem underlines: “Coral grows / wildly from bone. What have I made?” (‘Glass Slide; or, As I lay down in the instant,’ 58). Is human growth symbiotic or parasitic? Is it too late for us to co-create healthy ecologies? Polyp poses such questions, but not their solutions.