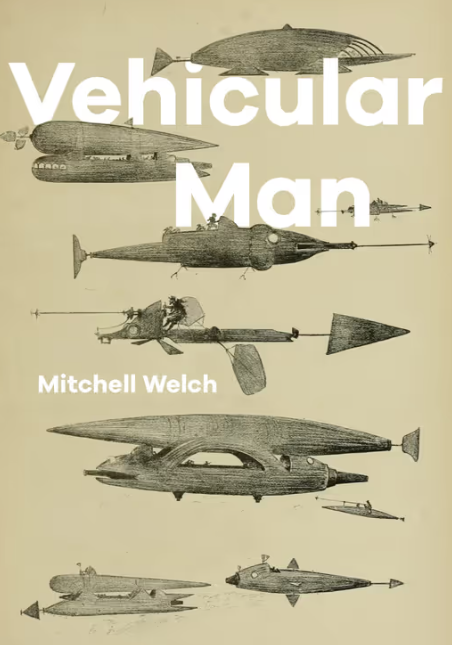

Vehicular Man by Mitchell Welch

Vehicular Man by Mitchell Welch

Rabbit Poetry, 2023

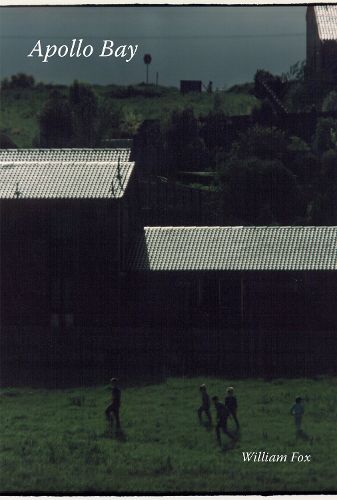

Apollo Bay by William Fox

Rabbit Poetry, 2023

Definitions of fiction and non-fiction are slippery. Each contains elements of the other; fiction can be based in non-fiction and non-fiction can include elements of fiction. Reportage, a non-fiction genre which is, by definition, based in truth still contains moments of fiction – not everything you see on the news is true. Biographies, too, are seemingly non-fiction, but the more they tend towards hagiography, the more they begin to engage in fiction. Even science has elements of fiction on a long enough timeline – remember when Pluto was a planet? Is it a planet again?

Rather than being definitions or categories that work on a simple binary, the relationship between fiction and non-fiction is dynamic. Something is always being measured: this account of the war is non-fiction with some fictionalisation; that biography has foundation in truth with some less-than-favourable incidents glossed over; this planet, as we understand it, is indeed a planet – no fiction there.

Non-fiction poetry is a confusing genre. I’m not sure if this very artistic form requires any basis in fact. Did Wordsworth really walk through that field of daffodils or did he simply glance over his sister’s shoulder and let the muse take over? Would ‘The Wasteland’ be any less poignant if the Spanish flu or World War I never happened? In the case of the former, I don’t think it matters. In the case of the latter, perhaps we can see how fact becomes useful to fiction. Or, perhaps, ‘The Wasteland’ is so eclectic and its words so abstract that any basis in fact becomes the realm of scholars while readers make their own meaning.

So why do we use these categories? Other than the obvious sorting utility (when I read a biography I can be sure there is some basis in fact, but when I read science fiction I’m sure most of it never actually happened, even if it is based on some scientific fact), this categorisation allows us to question the nature of truth and bias. How do I know this happened and does it matter if it did? In the case of Wordsworth, when we question the nature of his poem and the real events surrounding its creation, we can appreciate, if we’re being generous, some gender dynamics that arise in literary celebrity. And with Eliot, we begin to understand a poet’s response to world-shifting events. In poetry, non-fiction and fiction can overlap, the boundaries between the two categories more blurred than usual.

Which brings me to the two books being reviewed, Apollo Bay by William Fox and Vehicular Man by Mitchell Welch. They’re both debuts and they’re both published by Rabbit Poetry Journal as part of the Rabbit Poets Series. I don’t need to tell you what Rabbit is known for, but I will: non-fiction poetry.

Apollo Bay and Vehicular Man both work in that most non-fiction of sometimes-semi-fiction genres: biography. Naming these books as non-fiction lets us know that they are based in some truth, or on some true event, but their poetic nature allows us to reach beyond fact as it is and into the more subjective facts of experience and autobiography. That facts and the real are influenced by and interpreted through subjective experience is a realisation which makes this kind of poetry especially affecting.

William Fox’s Apollo Bay reads like a coming-of-age autobiography, exploring the poet’s experiences growing up in that eponymous Victorian coastal town. Non-fiction poetry often works with history and objects – notable figures and events, perhaps brands, objects, etc. Apollo Bay is a great example of this tendency. Fox uses these tangible things to express his own experiences.

The book begins with ‘Anne de Bourgh,’ a heavily anaphoric poem which lists the various excuses the poet, or, more likely, the poet’s parents, offered for his absence from school (1). There are several layers of non-fiction here, some even fiction-like or alluding to known fictions. Anne de Bourgh is that famously sickly character from Pride and Prejudice who is real in the sense that she actually is a character from that novel, even if that novel is fiction (I hope). And the genre of the sick note is of course usually non-fiction (the child seems unwell) with a bit of fiction thrown in (they are very unwell, so much so that they can’t attend school).

Appropriately, the poem plays with truth. It includes lines like “William had a viral headache hence his absence,” and “William had a viral headache, hence his absence” (1). These lines have the same meaning, but the second is split with a comma to suggest that the same excuse has been used twice. The slight modification in the second instance suggests, I think, some level of fiction. The poem is filled with such lines and afflictions, ranging from gastroenteritis to viral bronchitis. It finishes with,

William has recovered from the chicken pox, but will be picked up at lunch time, i.e. no sport. (1)

We doubt the veracity of the excuses throughout, knowing the shaky ground on which the truth of sick notes can be found, before finding the real affliction: an aversion to sport. The fiction of the sick notes allows us to appreciate the non-fiction of the poet’s true feelings toward sports. This flow of doubt to belief and then to truth is a great example of the usefulness of non-fiction poetry as both a classification and a genre.

In ‘Homebrand,’ Fox uses objects from the pantry as a kind of starting point to explore his past and understand, perhaps even come to terms with, his class position (14). His father brings home gifts from people for whom he’s worked. Things like,

cumquat marmalades labelled in a wobbly script or brusque and unmarked bottles of passata, tall and full-chested in reds and pinks. (14)

Perhaps we can assume the poet’s father is a tradesman, receiving homemade gifts for a job well done. But his mother

tended to mock these gifts as intrinsically dirty or below the purchasing power her family had earned. (14)

These objects and their very tangible features (homemade, labelled in wobbly script, or simply unmarked) act as markers of class. We might assume his father is of a working-class background and his mother is of a middle class one. Or, perhaps they both started as lower class and worked up. Fox ponders these objects and their features – not what he thinks of the features, rather what they are – and his mother’s reaction to them. In doing so, he investigates how these objects become markers of class, but he also investigates the ways in which responses to these objects construct ideas of class. He finishes the poem with “it took me many years / to trust affection / that wasn’t reputable” (14).

My favourite poem in Apollo Bay is much later in the book, and much later in the poet’s life. Titled after the book, or perhaps vice versa, ‘Apollo Bay’ presents the life of a quasi-teenager – of-age, maybe 20 years old – in a coastal town (44). It begins with the “[d]ense, straining headaches” caused by smoking “Reds” (44). He speaks to another patron of the pub, a “flannelette regular,” about the music on the jukebox It’s “unfair how they’re able to eek a melody / from such a demonically nondescript rift” (44). That comment by the poet to the patron brings the whole book into view. This coastal coming-of-age is ‘demonically’ nondescript. Yet somehow, from many non-fiction mundanities, some of which he fictionalises, or plays with in fiction-like constructions, Fox has eked (or should that be eeked) a beautifully melodic book.