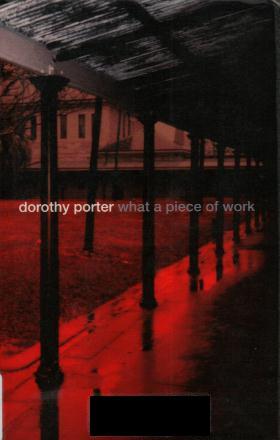

What a Piece of Work by Dorothy Porter

What a Piece of Work by Dorothy Porter

Picador, 2000

Dorothy Porter's previous verse novel, The Monkey's Mask, was a huge success – it won The Age Book of the Year for Poetry award, as well as several other prizes, and has been adapted for stage, radio and film. What a Piece of Work is Porter's third novel in verse, and takes its title from Hamlet's soliloquy (Hamlet, Act II: Scene II).

What a Piece of Work grapples with madness, obsession, creativity, healing, misogyny, lust and destruction. Set in an 'alchemical' framework, it traces the optimistic journey of the cynical Dr. Peter Cyren who, as the new supervisor of Callan Park Psychiatric Hospital, sets out to achieve perfection through the transformation of “sad or sorry mind(s)”.

The first-person narrative allows the reader into the mind of Dr. Cyren, revealing all the contradictions and vulnerabilities of his character, as well as the deterioration of his healing vision. However, his 'coolness' and cynicism may work against a deep engagement with the text, and prevent the (sensitive) reader from developing any kind of identification with, or empathy for, him. The effect on this reader was a distancing from the main character, which lessened the impact of the book's emotional climax.

Despite Cyren's faith in his ability to heal (“I won't rest | until there's not a sad | or sorry mind | I Can't fix”), he knows that “itchy energy | and nitroglycerine good intentions | are never enough.”

Like any kind of saint

or real artist,

fighting odds, suspicion

and the clock,

a psychiatrist's work

is never done.

Cyren's relationships with women create most of the tension. There is his chummy ex-wife, Monica – the Freudian; “pure” and “toxically trusting” lover, Fay (several years his junior); the memory of his beautiful, destructive mother; the institutionalised Penny-Jenny; the stripper/heroin addict/lover, Tamara; as well as Cyren's Anima – in its dual aspects of 'cripple' and 'flirt'. The pivotal relationship, however, is that between Cyren and his alter-ego, the mad poet, Frank – hater of women and Communists.

At first, Cyren clearly identifies with Frank – “like Frank | I hear voices || I hear the voice | of the river || the voice of dream”. He describes his lighting of Frank's cigarette as “an act of delicate intimacy”. Frank shares, with Cyren, images, dreams, fantasies and poetry. The pair are linked via poetry and 'saintliness' but for Cyren its is “ethically impossible” to share his own “glorious images” and he is “sometimes … jealous | of where Frank can go”.

He can travel,

he told me,

down the cracks

of the floor

in his ward.The morning

he has spent

in the Land of the Dead

tussling with Dante

over the true colour

of the soul…

What place is this Frank?

Will we ring its bell together?

Later, however, Cyren abandons Frank – afraid, perhaps, of his shadowy alter ego; or, recognising that there isn't room for two Saints in Callan Park. “Saintly suffering Frank” becomes “sanctimonious Frank”, capable of violently destructive emotions:

the Frank that kicked in

a television set

the Frank that cracked

the jaw of a strange woman

laughing too loudly at a party.

Cyren leaves Frank “in a locked ward | with no books | paper or pens”. He knows it will “kill him” but “these things | happen” and Cyren walks away from the “rat” of “friendship” to “forget Frank's | terminal rat's eyes | gnawing …[his] back”.

The studious reader, well-read in literary critical analyses of Australian poetry, might discern allusions to the poet Francis Webb. Webb's “Ward Two” poems, also set in an institution, are poems from within the walls of hell. Here, “fire clashes with fire” and the poet/patient declares: “Of pain's amalgam with gold let some man sing …” And it would be easy to infer that Porter has taken up this challenge with the (siren) song of (Saint) Peter Cyren.

Throughout Porter's novel, images of fire and burning – both healing and destroying – suggest a private hell and a desperate need for some ritual of purification. But will Dr Cyren, artist/alchemist/devilish saint, rise from the ashes of his drama?

The reader is left free to make his/her own judgement.