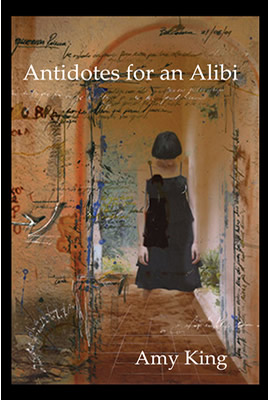

Antidotes for an Alibi by Amy King

Antidotes for an Alibi by Amy King

BlazeVOX books, 2004

Antidotes for an Alibi is at once intriguing and irritating. The surrealist poems are complex, evocative, and a danger to review: am I overlooking something? Is there an obvious reference I've missed? Am I just an insensitive clod?

Critics of the 'unintelligibility' of modern poetry will find plenty of ammunition in pieces like 'I Only Ever Sought Approval':

Persian carpet and wraps of crinoline delivered.

All flesh is grass, stews the unrequited air nestled

in my lung base. The universe flowers at my feet?

I only eat name

brand lace when I'm in your fallen graces. Cleanly confess

your work ethnicity within the arena of pigeon killers on

balance. I expect an inking heart will herein take my place.

This seems much the style of poem that Gig Ryan favours at the Age: a chaotic stream of images that serve as a metaphor for the disordered world the poet sees around them. In the last 50 years the surrealist technique has, to my mind, been superseded by confessional poetry, where a strong narrative component gives a sense of character to the work of poets like John Berryman, thereby ensuring their longevity. In contrast, the surrealist approach often yields lines of great beauty and power, but rarely leaves me with a clear picture of the poet. In King's case the poems have personality, but don't impress her personality onto me – she remains an elusive and whispery outline. In an era where the poet is as much the product as the poem, this may prove to be a handicap for her.

One similarity I do notice between King and the confessional poets is the infidelity that haunts her work: 'We twitch within the crosshairs / of passion and make ways / full of wallet, lies and photographs' ('Delicate Tasks'), 'Wrapped in personal pity, betrayer sphinx slinks / and eats' We make wine to toast the cross and tender liars' ('The Spirit is Near'). King approaches her betrayal in a resigned manner; there is little anger in the book; no Plathian or Wakoskian outrage. She entrenches her sorrow in lines like 'He played a sleepy harmonica / that pushed puddles to weep' ('Theory of Games') or 'the rain subsides and angels gather / at some distance, planning / their needle and thread' ('Off-Balance Romanticism'). I discern a tendency to keep emotion at arm's length: the wordplay King engages in throughout Antidote for an Alibi is most pronounced when love is the topic: 'Since then I will not make love / until I am in it' ('Sixteen Things You Should Know'), 'I remain loving you / if love is the word remaining' ('Breaking Story'). The lines still have punch but appear slightly whimsical, distanced from the heartbreak that spawned them.

King is at her best when conjuring up anthropomorphic imagery like 'a dryer choking on quarters' ('Up and Down Stone Mountain'). She sees humans, animals, inanimate objects, and natural phenomena as part of a continuum of life, not a series of integrated but separate parts. For the most part, she situates her vision of life in the urban environment: 'These streets report back to me' she says in 'Everyone Wants to Know'. At this point I am struck by the tonal and thematic similarities between her Antidotes for an Alibi and Ben Marcus's experimental 1995 book (novel? collection?), The Age of Wire and String. A hallmark of the successful writer is their ability to create a self-referential world, and King, like Marcus, has succeeded in forging her own (forgive me) kingdom. It is a world at times absurd – 'In the sacred circle of native life / I am a picnic table' ('Move to Modern Times') – at times in debt to what seems like automatic writing – 'Godmatter, godmanner, godbreath, half-asleep' ('In the Beginning') – and, at its best, self aware:

triggering the lightest duties

in premonitions that I might only ever

show the beginnings of things, leaving

the rest up to outside players,

actors hired without proper audition

('American Histories')

This is the sort of depth I am looking for. King's premonition is correct: she does tend to start things but not deliver. Consider the powerful opening of 'Evening In':

Mother phoned the premature death

of father to me. A machine shuffled

her words. I played back the story

of my childhood and grieved.

At this point I am ready to be staggered. I know Jarrell felt differently, but I want poets' bloody arms and legs. I want to hear what their words cost them in terms of their health and finances; their domestic bliss and sanity. Instead, 'Evening In' trails off into images of an enchanted little kettle, home-ground coffee, and a hazy blue living room light. Pretty, but emotionally unsatisfying after the gravity of the opening. She only showed the beginning of the thing.

This being said, several of the best poems are self-contained, consistent, and linear:

There is a deliberate pleasure in watching

Someone smoke cigarettes. Even the echo

of that sentence smells like a stolen observation

that the smoker is deeply, darkly thinking.

In books, they brood; on screen, they are the rebel

or daring victim being slowly, unknowingly undone.

I have always wanted to occupy my mouth

in similar fashion and gather great thoughts

from the shadowed glow erasing my face.

I suckle sweet cigar substitutes instead:

savor the proximity of nature we're taught.

Toast the lung in all its sanctity and encourage

its diverse role within ourselves. As always,

let the credits scroll down your face

before stubbing out the coal.('A Final Note')

Surprisingly, this is one of the few poems in Antidotes for an Alibi not previously published. I imagine it is her latest work.

The book as a whole is somewhat harmed by a lack of structure. The best way to enjoy Antidotes for an Alibi is by delving into it at random, letting the amorous overtones of lines like 'I want to touch you with some regularity' ('Story by Sentence') impress themselves quickly and favourably before the cognitive component of the brain starts asking awkward questions. Approached en masse, the poems rapidly fatigue the reader's eye and mind with their blocky, stanza-less structure. The fragmentary style and absence of punctuation do not help either: only twelve of the book's 63 pieces contain any sort of break between the lines. I find it difficult to imagine that anyone could enjoy more than half-a-dozen in a single sitting; the poems make too many demands on the reader in and of themselves, let alone when parcelled in this manner.

While John Leonard disparages the use of widely spaced words to convey meaning – see his poem 'Confessional' (Island Summer 2004) for a handy checklist of this and other poetic crimes – I must confess something of a fondness for it. Admittedly, it is a technique that can be overdone (and at worst foster histrionics), but I think spreading out the words, or at least separating them into stanzas or couplets, would improve the readability of King's longer poems. More generous spacing would, to me, enhance the impact of a powerful measured piece like 'Moment of What's Next':

Factory producing trash

straight to bins and roadside excess

flows the length of this collapsing land.

Nearby two men talk at a two-person table,

scanning the faces of young local girls

from college eating biscotti over wine,

all flesh and thighs of summer.

They are in their paradise

and I sip softly beside them,

taking age to the backdoor

patiently to bandage it.

If I were reading this excellent poem to an audience, I would do so slowly, with generous pauses after each sentence and comma (save the last one). As it stands, the poem is presented as a block that encourages the reader to rush through it. I appreciate that this is the fashion at present but I fear the effect it is having: I have been attending the monthly poetry readings held at the Museum of Brisbane. It seems to me that the poets repeatedly rush through their work with little or no sense of pace. I would be most interested to hear Ms King read her work for comparison's sake. If anyone would care to sponsor me, I am prepared to undertake a short journey to the United States to investigate the matter. I will, of course, provide a detailed report on my return. Direct all enquiries to the Cordite editors in the first instance.

Steven Farry has been playing music a long time.