Cover design by Alissa Dinallo, Illustration by Lily Mae Martin

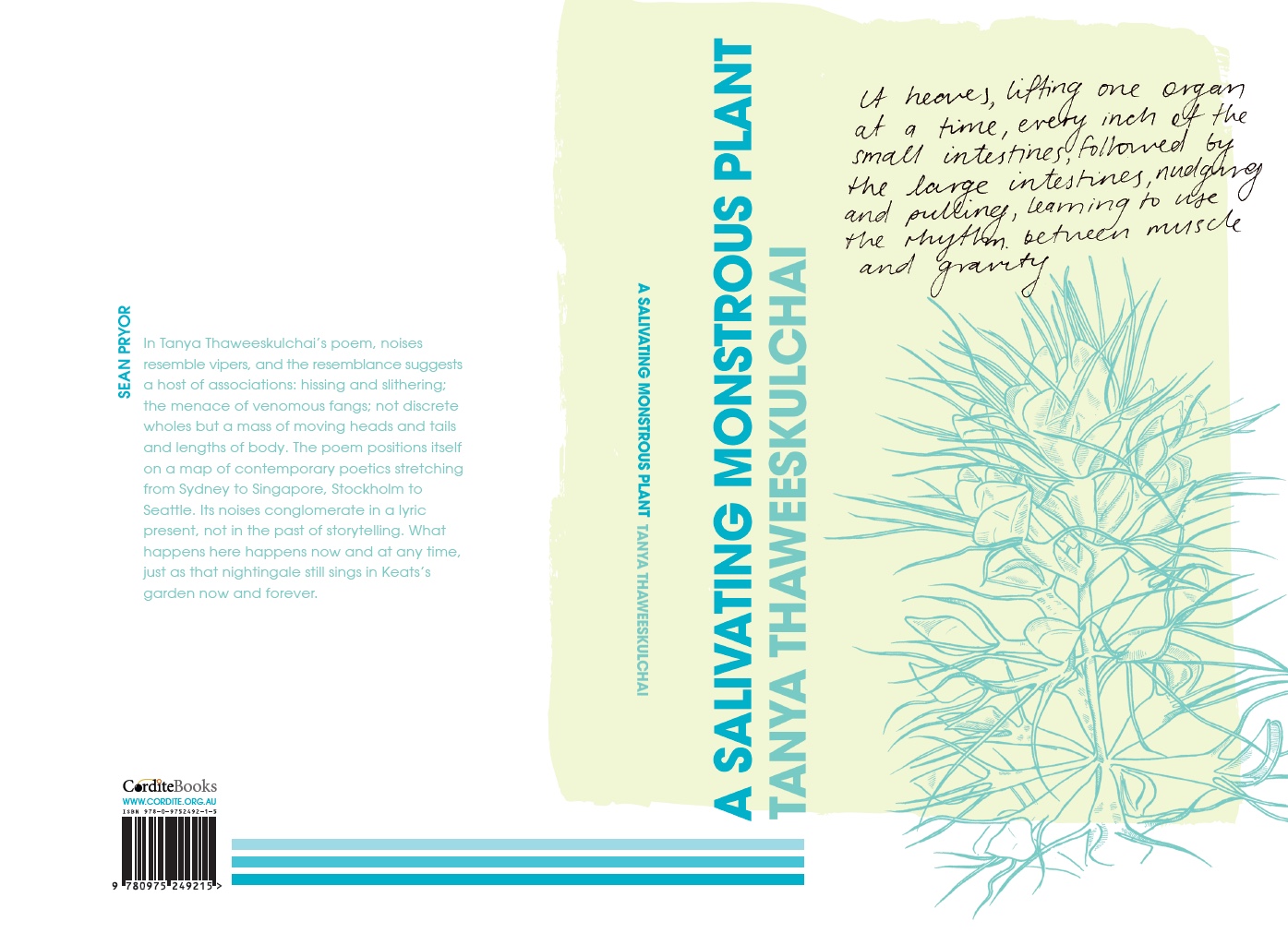

The greatest thing, writes Aristotle in the Poetics, is the command of metaphor, an eye for resemblances. The first overt metaphor in Tanya Thaweeskulchai’s A Salivating Monstrous Plant appears in its second sentence: ‘These noises conglomerate, building like a nest of waking vipers’. The noises resemble vipers, then, and the resemblance suggests a host of associations: hissing and slithering; the menace of venomous fangs; not discrete wholes but a mass of moving heads and tails and lengths of body. Real noises are given in terms of the imaginary, so that the sounds of what might well be an Australian garden – ‘crackling leaves, dust and dried mud’ – call to mind the hiss of snakes found in Africa, Eurasia, and the Americas, but not in Australia. Metaphor brings worlds together.

But in this collection, it rapidly becomes difficult to tell the real from the imaginary, the primary from the secondary, the literal from the metaphorical. The vipers may not be there, in the ‘real world’ of the poem, but in what sense are the noises and the leaves and the garden there? Even by the end of this first section, they seem less the scenic props of a narrative than metaphors for some other, unnamed experience or phenomenon, social or psychological. What matters as the poem progresses is the accumulation of words and images: leaves, shadows, eyes, skin, water, bodies. There is no stable literal ground on which to stand; we move in a world of restless resemblances.

I call A Salivating Monstrous Plant a poem – Aristotle was certain that poetry may take the form of verse or prose – but in its play with the conventions of narrative description and in its turn to the conventions of lyric presentation and lyric address, this long poem is nothing if not contemporary. In terms of technique, the poem positions itself on a map of contemporary poetics stretching from Sydney to Singapore, Stockholm to Seattle. Wherever we imagine that garden, its noises conglomerate in a lyric present, not in the past of storytelling. What happens here happens now and at any time, just as that nightingale still sings in Keats’s garden now and forever. This is the moment of narration or utterance, and it is the moment of reading: we as readers are intimately involved in the poem’s fluid figurative world. In the garden, at this ‘hour of commitment’, ‘the plant makes itself monstrous’, and some unidentified writer or speaker addresses herself or himself or itself or us: ‘Do this before anyone else can (so that no one else can): scrape away the thighs, stomach, breasts, arms’. And if sometimes this generic subject seems to offer a social or psychological ground and justification for the poem’s metaphorical abundance, at other times that subject seems itself the product of those accumulating images and words.

But Thaweeskulchai’s poem is not a puzzle, and the poem does progress. The ambivalence of narrative and lyric, like the ambivalence of literal and metaphorical, is not to be explained away. Instead, precisely these ambivalences give A Salivating Monstrous Plant its peculiar and compelling rhythm and momentum.