In an effort to get at least one person to critically appraise our magazine, we asked Stanford-based academic and poet Timothy Yu to review Cordite 10: Location Asia-Australia. And before you ask, of course he wasn't paid for it.

In an effort to get at least one person to critically appraise our magazine, we asked Stanford-based academic and poet Timothy Yu to review Cordite 10: Location Asia-Australia. And before you ask, of course he wasn't paid for it.

I wouldn't be much of a critic if I didn't start by picking apart the title. So: what is 'Asia-Australia'? The term suggests a continuous space, just as the phrase 'Pacific Rim' gets used in America to make Tokyo and Los Angeles wings of a single global mall. David Prater's provocative editorial makes the case for Asian-Australian contiguity, and even solidarity: 'Depending on where you live Asia might be … India, Japan, Australia, China … We are all boat people.'

But, as Prater points out, Australia – like America – continues to ruthlessly police its borders with Asia. Is 'Asia-Australia' a relation of identity or opposition? Is the hyphen a conduit or barrier?

My sense, in reading this tremendously engaging issue of Cordite, is that despite the language of unity, Asia remains outside Australia, as the object which is looked at, translated, read. Jill Jones describes her travels to Taiwan; Ouyang Yu gives us English versions of Chinese poems; David Prater's list of links surveys Asian poetries. But the issue hints that Asia-Australia can be an internal as well as an external relation, most evident in the illuminating interview with Asian-Australian writer Natasha Cho. This presents still more questions: What is the relationship of the 'Asian' to the 'Asian-Australian'? Is there any necessary logic in placing a selection of Chinese poetry next to a discussion of an Australian writer of Asian descent?

Such issues are familiar on the other side of the Pacific, where Asian American writers built their literary movement of the 1970s around the idea that Asian America was neither a translation of Asian culture to the United States, nor identical to the culture of white America, but some third thing produced out of the distinctive experiences of Asians in America. These writers struggled against the common stereotype of the Asian American as one caught between two irreconcilable cultures.

Looking over Cordite 10, I couldn't help but wonder if this bind was being reproduced. Opening the issue: a selection of Chinese poetry. Closing it: the latest Australian poetry. In between: interviews with 'Asian-Australian' writers Ouyang Yu and Natasha Cho. Are Asian and Australian poetries speaking to each other across this great divide? And are Asian-Australian writers cast as intermediaries, interpreters?

It's worth commenting here on the central role of Ouyang Yu, as translator, (bemused) interviewee, and Asian-Australian poet. Yu's translations do a brilliant job of bringing these Chinese poets into conversation with contemporary English-language practice, with energetic line breaks ('look sturdy on the / outside / but are broken within'), unexpected syntax, and casual grace. The divergent styles are similarly resonant, from Shen Haobo's narrative of memory to Zhang Ping's cheerful circularity, which Yu renders as a kind of product of the New York School's international affiliates.

Reading Yu's answers to Cordite's questionnaire, though, I wondered whether his curtness reflected a sense of the heavy burden of representation he's bearing, as Asian-Australian writer and as 'interpreter' of his native China. As a 'poet from China now based in Melbourne' (to quote his bio), where does Yu fit on the Asia-Australia continuum? (I note that locations do not become essentializing adjectives; Yu is 'from China,' not Chinese, and 'in Melbourne,' not Australian.) Yu's work reminds us that Asia-Australia is a place of translation, politics, economics, war: not identity, not opposition, but inextricable entanglement.

On the topic of the Asian-Australian writer, Natasha Cho strikes just the right note: properly skeptical of the label and its limits, yet aware of the work such categories can do for us. I'm taken with Cho's linking of Asia and Australia on the terrain of popular culture; it avoids the pose of the native informant ('What do you know about Asian stuff?', to quote her mother) while being true to the experience of the second-generation immigrant writer, whose relation to the culture of 'Asia' can only be a mediated one.

So how is Australian writing responding to this Asian conjunction? It's somewhat hard to say. As Ouyang Yu's translations sought to bring the Chinese poems up against an Australian poetic idiom, I hoped to see a corresponding gesture in the lively, exciting Australian poems offered here. But just as Jill Jones's journey to Taiwan is, strikingly, a story of silence – 'modern Taiwanese poetry' is nowhere to be found – the poems chosen do not register the pressure of Asia. No doubt it is illuminating to read the stark narratives of Shen Haobo against those of Duane Locke, or to compare Zhang Ping's use of repetition to Sally Ann McIntyre's. But I missed the conscious sense of engagement epitomized in Yu's translations. Selections of actual work by Yu, Cho, or other Asian-Australian writers would be a help. Though the presence of 'Asia' in Australia certainly shouldn't be reduced to that: Prater's citation of 'The Ballad of Razor Wire' suggests a whole spectrum of poetic response to the politics of Asia-Australia.

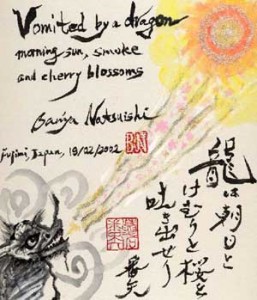

The most provocative suggestion may actually be the visual works by Banya Natsuishi reproduced in Cordite 10. These images juxtapose Japanese and English writing, yet integrate them into a single work. But most interesting in this context is the way English itself becomes calligraphic, estranged from standardized type. As Prater notes, this is the only place in the issue where an Asian script appears. Banya Natsuishi's work actually shows the seams between Japanese and Anglophone writing, and the limits of even the most advanced media in negotiating between them. Gus Gollings explains why Asian scripts cant be electronically reproduced. Banya Natsuishi turns the tables, creating an English writing that can't be reproduced either, except as a visual artifact.

The appearance of these hybrid images from Japan in an Australian journal make them a doubly potent embodiment of Asia-Australia, of incorporation and alienation. Asian and Australian writing, rather than regarding each other at a distance, might engage in a dialogue, even within the boundaries of a single text. Cordite 10 does an admirable job of laying the groundwork for this kind of dialogue. What remains to be done is a more precise mapping of Asia-Australia, one that understands this relation as both external and internal, present within Australian writing itself.