Pain as a Function of Romance

In Soledad Reyes’s The Romance Mode in Philippine Popular Culture, she notes that romance in Philippine vernacular literature relies on stereotypes and formulas which actively resist reality/realism, and therefore, also resist a realist critical reading. While going through Nora Aunor’s body of work, I found these elements of absurdity most apparent in her Guy & Pip romcoms. These interested me more than her aforementioned critically acclaimed films because my interaction wasn’t yet filtered through an academic-critical lens. While an academic-critical level of engagement with a film isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it does sometimes make it difficult to appreciate the things that ‘don’t make sense’ rationally but resonate on an emotional level.

It’s for this reason that I chose to narrow my focus to three of her Guy & Pip movies, namely: Always in My Heart (1971), A Gift of Love (1972) and Hindi Kita Malimot (1973). There is something haunting about having two people reenact different iterations of the same story over and over again. There are superficial variations of course: one is set on a cruise liner, one utilises ‘Dear Diary’ techniques as exposition, another involves twin brothers both played by Tirso Cruz III falling in love with Nora. But at their core all three of them used the same frames to convey romance (Nora and Tirso facing each other, backlit by nature), used the same tropes to create conflict (usually class differences or sudden death), and most importantly, revolved around Nora’s characters performing acts of labor coded as acts of love for which her characters are both punished and rewarded by Tirso’s rich-kid-playboy-with-a-heart-of-gold.

In Hindi Kita Malimot, for example, Nora’s character saves one twin brother from drowning and nurses him back to health in their seaside town only to have him die after their wedding. The other twin brother, also played by Tirso Cruz III, then comes to take her to their ancestral house in Makati where her true identity is hidden to save her from their mother’s cruelty. This is done by utilising the conceit that she was brought there to be the caregiver for their mother who recently suffered a stroke. As a result, Nora performs real labor to keep up the pretense and is subjected to spending entire days with the mother, who repeatedly bad mouths Nora’s character to herself, forcing Nora to agree that she is a hampas-lupa na walang karapatan. Later, when the second twin falls in love with her, the initial class conflict is reiterated. Not only did this film have repetition, it repeated itself twice in the same movie, with the same leading man, and Nora’s character performing the same labor of nurturing a rich person back to health.

This absurdity struck a nerve. I kept going back to 2010 and the bewilderment in coming to terms with the labor I was forced to do and the capital it gave me for attention-seeking and validation. It was absurd to keep playing whatever roles were asked of me – bad girlfriend, bad student, bitch – just because I was grateful to even have a role at all. Although the themes of female labor Patrick Flores brings up like pangkabuhayan (making a living), pakikipagsapalaran (risk-taking), and pagpapasya (decision-making) are present in these Guy & Pip romantic comedies, what I fixated on felt closer to pagpapanggap (role-playing) in romance. Why is inflicting pain or pananakit such a necessary agent of being a romantic female lead?

why = f(x)

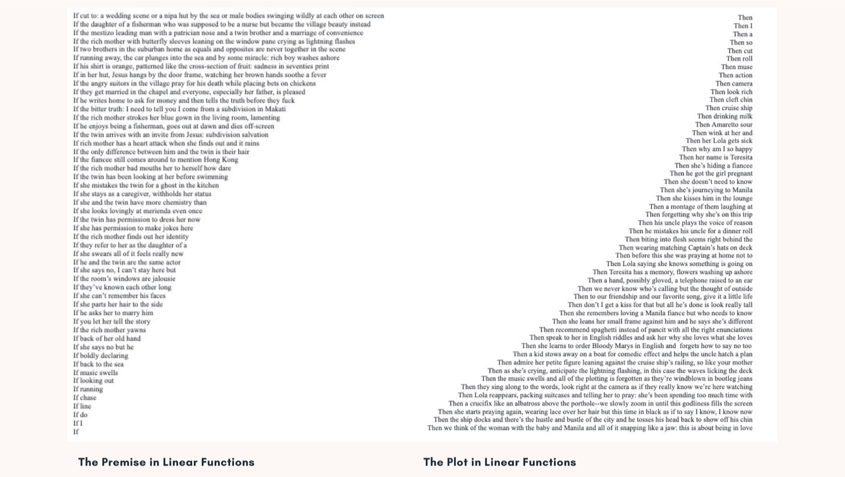

Poetry and mathematics have always felt very similar to me in that they employ experimentation as a mode of investigation, with an emphasis on form. Mathematical functions denote and illustrate the relationships between different variables1 by drawing them out on the Cartesian Coordinate plane. Poetry investigates the relationship between signs, signifiers, and their interplay with the human experience and the natural world by problematising what words could mean, what associations they could evoke, how the words sound, read, and look on the page, what contexts they can traverse; poems can also be plotted on an axis if we look at Roman Jakobson’s concept of the metaphorical and metonymic planes2.

Stills from the three Guy & Pip romantic comedies, screenshots of types of functions and their graphs, showcase of shapes of the different poems.

It also struck me that Jakobson literally talked about the Functions of Language, which described language as relational, in constant conversation with other words or experiences. The formulas of the Guy & Pip films (and even deviations from the formulas) also seemed to do something similar, making them perfect ekphrastic material.

That said, I wanted Functions:Poems to be more than ekphrastic work. I wanted there to be tension between the images taken from the films and the persona’s imagined poetic situation. I wanted the poems to be dynamic, to both illustrate and fracture function, and therefore, create something different altogether. To do this, I divided the poetry collection into three parts: linear functions, inverse functions and identity functions.

| Linear functions | Inverse functions | Identity functions |

|---|---|---|

| POV: 3rd Person | POV: 2nd Person | POV: 1st Person |

| The premise | The climax | The ending |

| The plot | The build-up | The ending |

| The scene | The limit | The ending |

| The leading man | The villain | The ending |

| The leading lady | The leading lady | The ending |

| The villain | The leading man | The ending |

| The limit | The scene | The ending |

| The build-up | The plot | The ending |

| The climax | The premise | The ending |

| The ending | ||

| The ending | ||

| The ending | ||

| The ending |

List of poems, parts, and their corresponding points of view.

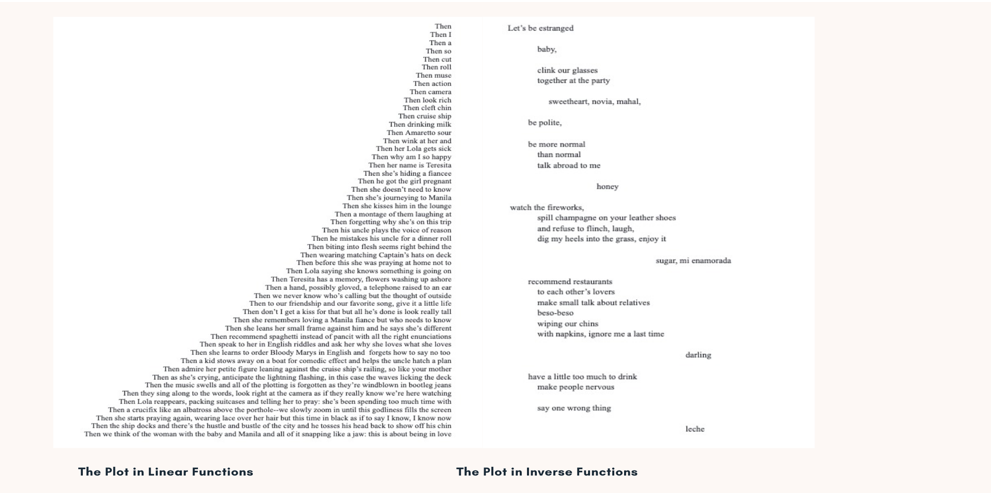

The first section, Linear Functions, is told primarily in third person with farther psychic distance and an emphasis on the shape of the poem on the page, with the mathematical constraint at the forefront. The examples below, The Premise and The Plot mirror each other and are in an If-Then pattern. When writing them, I was very conscious of poetry as a curation of images that created tension and new sources of meaning by displacing the images from their original contexts.

The second section, Inverse functions, contains poems literally arranged inversely to the Linear Functions and are told in second person. With the acknowledgement of a You, the I is now hinted at but not yet fully revealed. The number of images borrowed from Nora’s three films begin to lessen, and there’s a breaking-out of the tight constraints mimicking mathematical form. The ‘reel’ life begins to give way to the persona’s ‘real’ life. In my mind, this section was a way of meeting my ekphrastic subject in the middle, a way of saying hello and thank you, and I’ll take it from here.

The final section, Identity functions, is told in the first person, with the ‘I’ and the ‘real’ poetic situation finally being revealed. In this final section, we fully understand the suffering, the kind of emotional labor, the persona is being subjected to. We understand better what the different images were signaling toward. The form is now closer to what we would recognise as being ‘in verse’ or poetic form. The most important thing about this final section is the focus on the indeterminacy of endings. In Literary Theory: An Introduction, Terry Eagleton says, ‘Meaning, if you like, is scattered or dispersed along the whole chain of signifiers: it cannot be easily nailed down, it is never fully present in anyone sign alone, but is rather a kind of constant flickering of presence and absence together’. Endings are continuous and dynamic, both real and unreal.

Films end when they do to convey a specific emotion, to leave the audience in a certain mood. The Ending is never a capital-True Ending. When does coming to terms with oneself, with one’s place in society, with one’s place in the world end? Is there ever a point wherein we can lean back and say case closed on the female labor files? I don’t think so.

Nora paving the way for Filipino representation in the Philippines didn’t solve colorism in the Philippines. Nora portraying working class characters didn’t save Nora from suffering and bad political decisions in her real life. Even this experiment will grow old and become part of the established schema, the established functions of romance or female labor or poetry, which again someone will have to prod at, to provoke, to investigate.

I will leave you with one of the endings which I see as a trapdoor within the collection, taking us from Inverse to Identity, from the You to the I.