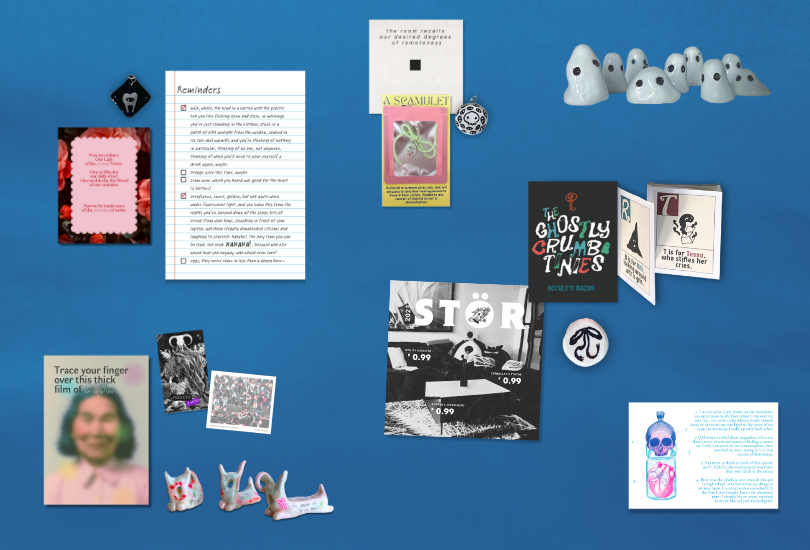

I send my friends messages about things that have amused me lately: waiting rooms. Yellow-dulled walls. Illustrations combining cats with konbini snacks. We share memes about how we shouldn’t worry about our jobs because we’re all going to die anyway, respond to each other with double-taps producing the quintessential ❤, because this is the bare minimum for intimacy in an era of being chronically online. Outside of the Internet, I’ve been looking for moments that force me into feeling more like myself, insisting there’s something else beyond our 9-5s, where ChatGPT is being championed to help us become more ‘efficient,’ deluding us into thinking we could be functioning members of society through AI-tinted buzzwords that suggest: You’re replaceable, so we convince ourselves to use the technology to keep up and keep our jobs: here’s a GPT for documents, for weekly presentations, for our messages to each other and even for our periodic self-reflections, where our selfhood is measured in quarterly KPIs or in how well we’ve collaborated on projects that were, in some part, created to support this shift towards AI. Two paragraphs in and most of us give up, ask ChatGPT to TLDR this please, just to save us an ounce of the time we always, always seem to be running out of. Worse, that ‘please’ cost us millions of dollars in fossil fuels and water. Worse, we said ‘please’ because we think AI will come for us as we slowly waste away. See: dead internet theory. The AI ouroboros and Roko’s basilisk. As if we didn’t grow up being warned about snakes. This homogenization of content sometimes feels like laundry. Wash, rinse, dry, repeat, and watch wide-eyed as the murky soapwater inches towards artistic discourse and turns it gray. I just hoped I could use it for math because metrics make my head hurt. Instead I discover everyone wants to be creative but we’re forced to take shortcuts. Instead I understand it’s because everyone’s tired of being tired. Stronger teammates have departed over their refusal to adopt AI into their workflows. Meanwhile, I tried healing my future grief with a chatbot that pretends to be my cat. Under a little side project called Occult’s Razor with my friend and collaborator Erika Carreon, I’ve co-written zines that engage with generative AI, feeding the machine and watching it spew thoughts as its own, observing this exchange out of some sense of morbid curiosity, because I’m convinced that to talk to ChatGPT is to talk to both the living and the dead, and what literary category does that fall under? This might be fun, we thought, calling this project our little ‘experiment,’ ignoring the visual cues this word was known for: many-eyed monsters emerging from test-tube explosions, a bolt of lightning striking a stitched-up corpse. In 2018, we published Budget Fortunes, pocket-sized cards written with the help of predictive text. They didn’t exactly dispense knowledge or give readers a peek into their future. They were simply sentences that sounded ominous enough, open to interpretation just like a horoscope was. They were also iterations of our first published work: 2017’s A Descending Order of Mortal Significance (aka, the tellingly nicknamed ADOOMS). Both projects meant to satirize the hold that tarot cards had over everyone at the time: that tiny element of chance, sentences in the 2nd-person meant to assume the imposing hand of fate, vague enough that they seemed specific. They played off our inherent curiosity to know what comes next, even though they actually borrowed from what came before. ADOOMS was based on existing information; other sources prompted our writing prompts:

- What if we wrote stories based on delusions like Capgras and Morgellons, use them as portents signifying our declining collective thought?

- What if we collaged engravings from the public domain to create these scenes, use the past to illustrate the future?

and so it felt natural to create Budget Fortunes as a follow-up project. At the time, smartphones were autocorrecting our ducking errors; words appeared over our keyboards in groups of three. We were worried about where all this was going, but for us as writers, these new tools became irresistible. Learning Language Models (LLMs) and generative AI were slowly being built, and while most artists remained cautious, we wanted to use it to take risks! have fun! innovate! After all, with everything going on in the world, couldn’t we write something that lets us unburden ourselves while still interrogating what art could look like in collaboration with a machine? For Budget Fortunes, we used Botnik Studios’ Voicebox app, ‘a creative keyboard for remixing language.’ Very Goldsmith, very Clarissa Darling, and very new in the Philippines, where randomizers and literary experiments were only just gaining attention1 or dismissed as theft or tagged as illegal.2 This public ostracism and ambivalence towards new creative avenues only challenged us to publish more transformative work, forms of criticism and textual appropriations rarely found in the country, especially as we witnessed the few we knew being taken down with the force of the law. Using Voicebox was easy enough: it was inspired by our smartphones’ Suggested Words feature, but instead of the dictionary, it remixed Nirvana lyrics, collections of pancake recipes, Buzzfeed quizzes and Bachelorette season 8 transcripts. Even better, you could upload your own source text to build your own keyboard just like we did, not knowing it was one of the earlier faces of ChatGPT. It was a project of curation, the combinatorial creativity I’d made part of my practice, a practice that meant I would create a card dispenser out of cardboard to distribute these 20-peso Fortunes at the turn of a dial, an attempt to mimic the oracles of Quiapo, and again an attempt to siphon this ambiguity through a complementary tactile experience. In an interview with Cornell Press, Botnik founders Bob Mankoff and Jamie Brew described their invention as ‘playful’ and ‘only semi-serious’, noting that it also raised questions on the ubiquity of AI, how it seemed like we outsourced our brains. Ultimately, they ask: ‘[W]here does the computer end and ‘I’ begin?’3 I think therefore I need to do the dishes; I need to pay the electricity bill. I need to work, work out, and work through my emotions everyday until this body finally gives up. Meanwhile, the computer doesn’t even have to go to the supermarket to tell me which watermelon is the sweetest. It doesn’t have the tastebuds to enjoy one bite, but could describe it in a way I couldn’t. This made me even more curious. I wanted to test it and test myself, see what else we could do. In 2023, we published STÖR, a catalog of thought experiments featuring AI-generated art and AI-assisted text. The intention behind this was to call explicit attention to the Uncanny Valley-ness of AI output, suggesting, in these surreal black-and-white images, that AI couldn’t replace humans, especially artists: just look at those impossible hands, those noodles for fingers, figures that resemble flaps of skin trying to escape from itself! We wrote this zine on-and-off during the pandemic, noticing our peers cope with the loss of routine through furniture and homeware. Again, it was our response to ‘what’s going on these days’: an inquiry on the current landscape, a narrative fueled by questions on the boundaries of authorship:

- What if thought experiments like Kavka’s Toxin and Theseus’ ship were sold at IKEA?

- What if we input these thought experiments into a text-to-image app, just to see what these thoughts look like to a machine that couldn’t think for itself?

We wrote it as horror, as text that reflected its own failure. ‘Enjoy life without flesh, feel freshly drained of color.’ was one of the lines we’d curated from the Botnik keyboard. A line from a machine, but a line that captured our dread from being cooped up in our rooms, from being exploited by government officials, from feeling helpless no matter how much we tried to help. It was also one of the zines that took us the longest to write because we were getting so many errors from Botnik, which meant we had to use a different tool called InferKit that served a similar purpose. It’s also possible that this zine took longer to write because we were unsure of how it would be received. How free was free expression; how did we know if we had crossed a line? Our sentiment towards AI tools remained the same. We kept them at a distance: as a constraint, a technique, and yes, ironically, a prompt that gave us results we could later manipulate. But as we published our zines, the world kept spinning: AI tools progressed faster than we could write work that critiqued it. InferKit has since been discontinued, announcing on its website that it ‘has become outdated.’4 Botnik’s Voicebox still exists, but like InferKit and many others, it’s been eclipsed by ChatGPT. And as these tools developed too much too fast too often, we started to examine the issues that came with it: the struggles of creative production amidst unending bowlfuls of AI slop, dependency on a machine, privacy and ownership – even though initially, we were just searching for this generation’s version of Oulipo: another way to stretch language and play with form. I’d read articles condemning AI in art alongside articles on the principles of ethical data scraping; I agonized over nuances of copyright and costs as I continued searching for better avenues to support local artists. And with Wayback Machine’s screenshot of the old InferKit website, I remember this important note that I’ve always been terribly conscious of: ‘Who owns the generated text?’

‘… consider that the neural networks were originally: 1) designed and trained by large tech companies who licensed their code under the MIT license, 2) learned from millions of web pages containing content in which many people hold copyright, 3) are hosted by us (we waive all rights to the content) and 4) are conditioned on the prompt you give it (your own content).’5

It would be so easy to say we’d been stealing, but I grew up with erasure poetry and found text. I’ve played literary games like round-robins and Exquisite Corpse. I’ve toyed with plot generators, ideated with a Twitterbot, written fanfiction, and shared some of my own work for free for other artists to do as they wished. (Fuck my drag, right?) Columbia University’s The Literary History of Artificial Intelligence exhibition also traces this all the way back to 1890, curating ‘examples of algorithmic composition, such as prose and poetry written by machines, alongside literature written with the aid of algorithmic and combinatorial devices.’6 It showcases pages from books like Wycliffe Hill’s Plot Genie series, which lists dozens of ideas for writers to use: climaxes and surprise twists, locales and love interests; some were even written for the comedy and detective genres, compiling several tropes we know today. This came with a spinning paper wheel: a Plot Robot, meant to produce a random number corresponding to the list, along with similar devices, which, in a way, inspired the card dispenser we built for Budget Fortunes. But throughout the exhibit, I notice how: (1) writers have always had some form of help to make art, often through the world that they’re engaging with; and (2, more importantly) writers still had a hand in writing what they’re writing. Jennifer Becker encourages us to look at AI ‘as a supplement to the creative writing process – a hybrid, rather than a whole.’’7 And tbqh, this is what makes the most sense to me at the moment, in terms of what I think is combinatorial, in terms of how I view my work within this much world, because I know the dangers of relying on AI too much, and I know we can’t lose our heads, because even my job tells me we need to show up for it, learn it and teach it some form of good, because without our intervention, things could be so much worse –

- See Anthology of New Philippine Writing in English, Kritika Kultura Literary Supplement No. 1, published March 2011 ↩

- See Anvil Publishing V. Adam David by Maria Karla Rosita V. Bernardo for the Philippine Law Journal ↩

- See the interview BOTNIK versus the Romantics! Can an App Help You Write like a Romantic Poet? by Bob Holman and Steve Zeitlin ↩

- RIP InferKit by Adam Daniel King ↩

- Internet Archive. “Text Generation.” Archive.org, 2025, web.archive.org/web/20220501203530/inferkit.com/docs/generation. Accessed 9 July 2025. ↩

- See The Literary History of Artificial Intelligence, an online exhibit by Columbia University Libraries ↩

- See AI Literature: Will ChatGPT Be the Author of Your next Favourite Novel? By Jennifer Becker ↩