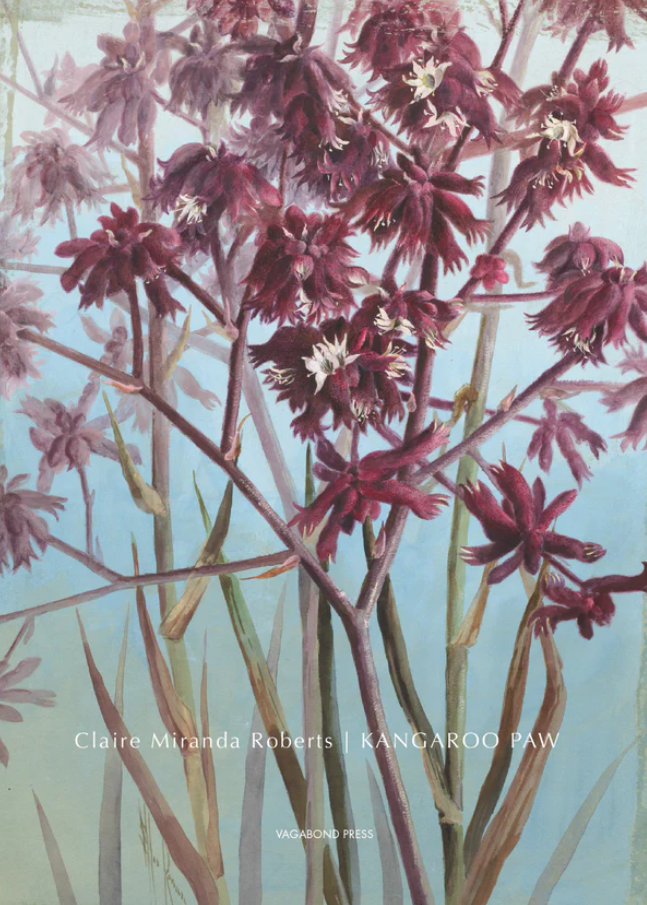

Kangaroo Paw by Claire Miranda Roberts

Kangaroo Paw by Claire Miranda Roberts

Vagabond Press, 2023

Gentle Creatures by Stephanie Powell

Vagabond Press, 2023

Two paths unfold. The first, a cut through a mathematically precise study where landscape meets self, transposed over the growth patterns of flora. The second, an expansive suburban saunter through a treatment of identity and memory of place, plotted cartographically. These pathways have names: Claire Miranda Roberts’ Kangaroo Paw; Stephanie Powell’s Gentle Creatures. Both were published by Vagabond Press in 2023. Whichever line one walks one will find that small beauty and close observation dominate the attention of these poets and their intriguing, highly individual collections. For all of their vast differences in style and approach, both share a core fascination with lineage, with landscape. These collections are carried to ends which balance each other and make for a stimulating comparative study. For Roberts, lineage is genealogical and distant, sought after and spun from fragments; landscape is an idea of home obscured by intentional, absent spaces within her formal structures. Powell’s lineage is closer, the second half of her collection is dominated by a study of her own childhood, while the collection opens with a narrative focus on the return home to a familiar landscape after a period of absence.

To begin with Claire Miranda Roberts’ Kangaroo Paw is to become beguiled by sparse, suggestive syntax. In her 19-word opening poem ‘Armillaris’ she conceives a subtle genesis:

duplicate saplings are shyness— the extension of politeness to a stranger. (9)

There is the possibility that on a first reading, one might rush past what is contained within Roberts’ “clasps / of calyx” without recognising her crisp intentionality (9). But on a second or third reading, the influence of Emily Dickinson becomes apparent, an influence which the judges of the Helen Anne Bell Poetry Award Bequest in 2022 also named. Phenomenologically driven language is paired with tight formal constraints to astonishing effect – of the first 20 poems the longest is only 12 lines, and very few of these lines hold more than 4 words total. Operating as she does in such sparsity, especially in her free verse, Roberts manages to create incredibly vivid images of each flower, tree, and shrub to which she gives her attention. Roberts’ precise language allows her to generate, in so few words, a highly suggestive, emotive tone. Reading between the lines to trace the diffuse, pensive ruminations of the collection, one realises that both content and form mimic unpredictable patterns of growth. Line breaks and white space craft shapes and reveal the poet’s presence. The flora of these poems seem to exist entirely within Roberts’ microscopic observation, but poetic motivations begin to emerge:

If I stay long enough

I may become

everything around me: many

pinks

in the dusk

(‘White Jasmine,’ 18)

Roberts’ botanical framework zeroes in on the landscape and its colours, its wider feeling, and is crisp and direct in its force. It discloses much about the observer. Why these colours, these shapes? Why these reflections? There is a somber, melancholy quality to the writing that allows us to feel Roberts’ presence in the field, which is remarkable considering how minimal the interjections of self are within her poems. Yet where contemplations on self and past do appear in Kangaroo Paw, Roberts deftly chooses the moments to interweave them:

Long ago

in a dark land

maternal lineage twice

removed

I’m searching for her

record

in the silt down the Snowy

River

(‘Tides,’ 12)

My future is backward

I should be far from here

in the opened summer

(‘Backwater,’ 11)

The concern in these poems is not only for a feeling of the past, but for familial legacy and its record held by the land. In Roberts’ personal blogspot ‘The Other Beauty,’ she details the genealogical research centered on her third great-grandmother and her extensive search for scraps of family history traced through maritime records. ‘Tides’ translates this research into emotive image creation, “I’m searching for her / record / in the silt down the Snowy / River” (12). This context grants an interesting clarity, but is it essential to understand exactly why Roberts is so intent on observing the natural world around her? I don’t believe so. The mystery adds to the overall effect of reading this wonderful collection, the reader is on their own search for knowledge. Obfuscation and suggestion work hand in hand. There is so much detail which begs for deeper consideration and a vast deal of mystery within the detail, undercurrents of unspoken places. Through a fascination with colour and scent, with shape and impermanence, this collection thrums with life. It is expansive and demonstrates the relevance of tight formal constraints to contemporary poetry. Alongside free-verse, Roberts uses the cento and sonnet forms, as well as erasure. As disclosed in her ‘Notes’ section, she quotes from and interprets other poets’ works, as well as snippets from her mother’s diarised botanical notations, various interviews, the King James Bible, and the Oxford English Dictionary (59, 60). Hidden within this ‘Notes’ section is one revealing disclosure, an allusion “to the correspondence between Walt Whitman and Horace Traubel” (60). To note such an allusion, and work within it, is significant. It demonstrates the certainty with which this work was produced – this is a poet who loves poetry. The collection is at its best when Roberts inserts herself into the botanical world around her, when she engages with the mysticism of the natural world otherwise belied by her tendency towards scientifically slanted presentation:

I want to pass

through trees

into their grey-green

amphitheaters—

their revealing

and concealing effect.

(‘Telling,’ 19)

There is so much at work in Kangaroo Paw which hides below the surface. The past is obscured yet the poet has returned to its locus, previously known to her, and she is changed through methods undisclosed. As we learn in ‘Pact,’ “I thought I knew my past / then I returned / / and I was not / cleared of this place,” we are not privy to the how or the why, only to the familiar dissonance of returning home and being not the same as before (28).

In her ‘Afterword,’ Roberts notes her training as a visual artist (54). As Robbie Coburn discusses in ‘The Human Voices of Flowers,’ his rightfully glowing review for The Rochford Street Review, this training is also, evidently, one of the sources for her mastery over the poetic image. So too the lessons in grammar taught by her mathematician father have evidently contributed to the perfectly punchy use of space on the page. No verbosity here. The artfulness of this debut collection is heightened by Roberts’ level of control. There is a sense of intent which dominates Kangaroo Paw. Claire Miranda Roberts is in total mastery of what she allows us to see, and it makes for a fantastic read. In her own words, “what is a poem? Something we hide the Self within” (‘Afterword,’ 54).