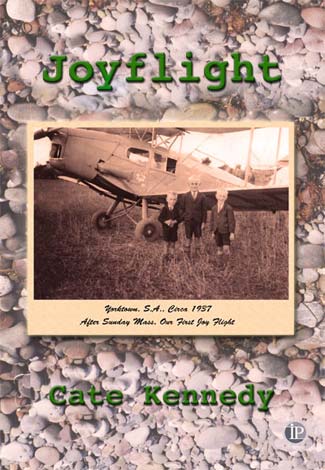

Joyflight by Cate Kennedy

Joyflight by Cate Kennedy

Interactive Press, 2004

Cate Kennedy's Joyflight is distilled memory. It is a manifestation of time, place and history, both intensely personal and instantly recognisable. Joyflight is a book divided. It begins with `that pure torn-open moment': A collection of small epiphanies in which the individual is forever altered.

The title piece `Joy Flight' is precisely this experience. In the first stanza Kennedy extracts from the stoic, mountainous image of her father, a precious childhood memory of hopeful anticipation. The impact of sorrow releasing a small fragment of hidden emotion, long buried:

My father's stories

must be provoked from him

by some landslide of sorrow;

a lost city's foundation revealed by shifting earth.

Only after the death of two brothers

does he relate some childhood moment

of a Sunday after Mass, when a Tiger Moth

touched down on a patch of ground

offering joy flights.

This is Kennedy's tribute to those `three blond boys taut with longing', whose joyful experience is shared by all those who read the poem. This poem is an offering. A gift, passed directly from the poet to the reader:

from hand to cupped hand,

carried warm next to the skin,

recited for courage.

Kennedy thoughtfully examines this `small recovered legacy', as a thematic thread that binds together this collection. In `Following the Game', she reconstructs the complexity of adolescent emotions. The oscillations between boredom and desire set against the backdrop of the oppressive heat of the Australian summer.

lime cordial summers

the telly murmured three day tests

in the only room with a fanwe would end up there, collapsed

in cut-off jeans

stupefied

with the white lethargy of school holidays

Later in the poem Kennedy reveals the mounting tension and impatience which underlies this apparent stasis:

we wanted the burning vinyl of bench seats

boys who smelled of petrol

a cool change, quickening pulses

wanted a roar, wickets flying, limbs

taut with anticipation

This collection of poems is refreshingly unpretentious. The language employed is lyrical and honest. Rather than toying with syntax, punctuation or grammar, the simple beauty of the language itself commends Kennedy's talents as a wordsmith. She is an unabashed lover of language:

My mouth tastes each satisfying vowel and consonant,

delicious with something scarce made abundant:

Saffron Milkcaps

there's not one thing about that name I don't like. (from `Collecting Mushrooms')

Kennedy has dedicated this collection of poetry to her father. After reading the poems contained therein, it was of no surprise to me that in the dedication, Kennedy has quoted Pablo Neruda:

We have to disappear into the midst of those we don't know, so they will suddenly pick up something of ours from the street, from the sand, from the leaves that have fallen for a thousand years in the same forest, and will take up gently the object we have made. In that object, poetry will live…

The above quotation perfectly describes the poetry Kennedy produces. Every human experience creates a possibility to explore, a story to tell. Everyday objects whisper their secrets into her ear. Both Kennedy and Neruda expose and brilliantly articulate the sublime nature of the environment, of time, of subject, and of human experience.

Kennedy is fascinated with the concepts of time and permanency: In `This Is Summer' she surrenders herself to the decadence of the Australian summer. The heat, the insects, the rampant desire to consume and multiply, this is a world of voracious hunger and an explosion of growth. Unlike the human world, this is a world where nothing is wasted. Where even the mightiest in the food chain become food when it comes time to `settle in the path of five billion consumers':

if you just lay there

surrendered,

you would be so efficiently dismantled,

broken down into salts and sugars

your glazed irises sipped delicately by ants

if you still stared, unblinking

flowering weeds would spurt through the sockets

your greenhouse ribs would be twined

with the voracious red tongues of blackberry vines?

Nothing here is permanent apart from the never-ending cycle of life and death. There is no sympathy in this organic orgy of life:

eyeless, ruthless, perfect

it is all perfect – it is stupefying

it is never finished.

The second half of the collection is entitled `burning of the world's almanac'. Kennedy draws experience from her travels to Ireland to expose humanity in all its monstrous beauty. `The Poor Commissioners', for example, is a poem written about 150 people who died in the 1849 famine after being denied sustenance at the poorhouse, County Mayo, Ireland. This is a poem of quiet outrage, a powerful statement about poverty, class, and bureaucracy:

And the men in the house, never dreaming

that this would be the moment seized by fate

to expose them

this, which was commonplace, no doubt;

they were Commissioners, only that, righteous with due process,

stamps and nibs put away for the day, and now

dealing with a nuisance, irritable,

pushing the last of the bread

around their plate.

This poem is a narrative for the voiceless. A narrative from which parallels can be drawn with today's world, a world peopled with more refugees and dispossessed than ever before in history. It is Kennedy's demand for recognition of the human face of suffering:

Tomorrow we will draw a red line in the ledger

pious and put-upon, holding this burden like a full plate

against our memory of the cold

A particularly striking element to Kennedy's writing is her strong sense of irony, a highlight of several of the poems in this collection, such as `Irish Singing Here Every Night' and `Potions':

We fall for it every time, us second-wave women.

The mystique of the potions,

the idea that what we have inherited and absorbed can be foamed away

that a soothing astringent will cool our smothered rage

that there is a new surface, waiting to be revealed

beneath the old surface,

that our skin is starving

and must be fed.

It is difficult to know if I have done justice to Cate Kennedy's Joyflight, as each poem deserves individual mention and critique. Each has a particular story to tell and a profoundly beautiful method of conveying the narrative. Kennedy has captured that `pure torn-open moment' and has passed it to the reader, in the form of a book.

Jess Star lives in Melbourne. Is wildly passionate about brilliant writing, social justice and whatever she's fixated on at any particular moment. She's currently studying an Arts/Law degree at Deakin University and is a sometimes-masseuse.