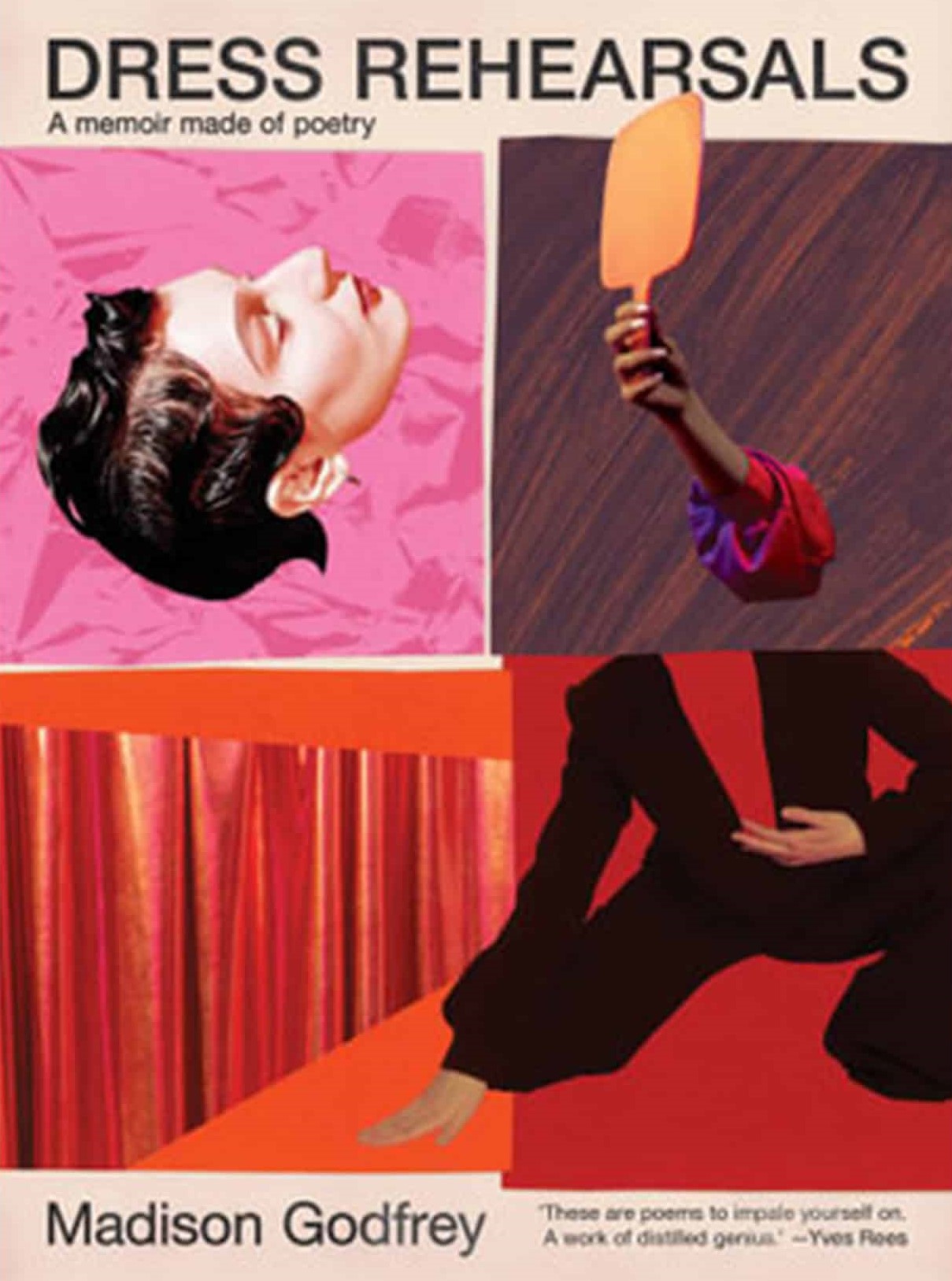

Dress Rehearsals by Madison Godfrey

Dress Rehearsals by Madison Godfrey

Allen & Unwin (JOAN imprint), 2023

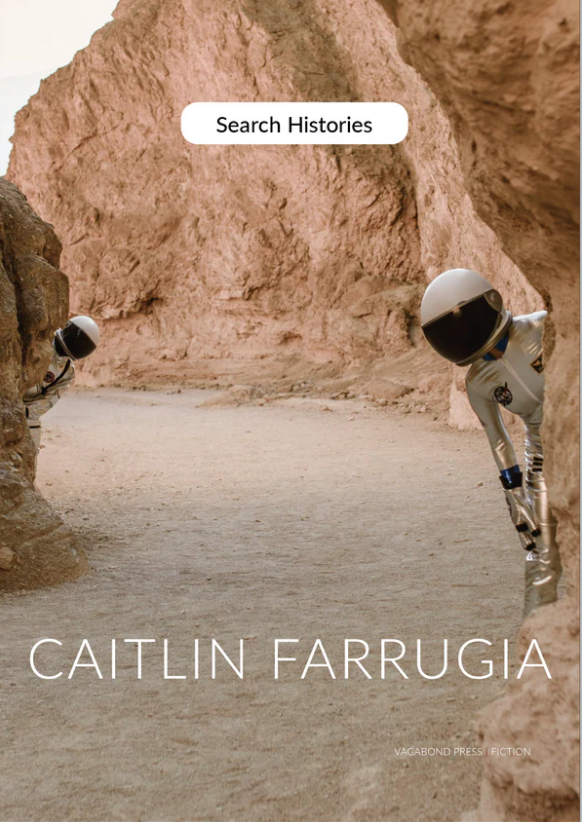

Search Histories by Caitlin Farrugia

Vagabond Press, 2024

Madison Godfrey’s 2023 collection of poetry is, as the cover and title imply, like staring into a mirror to find only the arm that holds it up – a dress rehearsal for a made-self that is trying to find its way towards an exciting and liberated life in a cis-gendered, heteronormative world. Godfrey, for all their sheer decadence, is a slick, street-smart, purveyor of performativity in their poetry, capable of deft transitions between the subtle and the blaring, linguistic contortions that weaponise humour and effectively nullify neutrality, wasting very few words in unpicking the less-than-delicate threads of the gender binary, gendered violence, femineity, and queerness as prop.

In the opening poem, titled ‘When I grow up I want to be the merch girl,’ Godfrey writes:

Sighing like a swimsuit model who got fired yesterday. Boyfriend’s band shirt tied on one side. Silver belly ring aligning with the trestle table. Glaring at her Nokia. Permanent marker forearms. (3)

Here, Godfrey speaks both from and to a place of caricatured naivety, outlining a desperate and overt attempt throughout their life to be a certain type of woman. In doing so, they explicitly name idolisation as absurdist, and performativity as an act of self-disappearance and self-renunciation, but, also, ironically, how this performance, when knowledgeable of its own absurdity, can be self-elevating. In the last poem of the first part, ‘Spiders on my lash line,’ Godfrey writes:

I want to visit hyper-femininity like a city built by men, who mapped the streetlamps but never pole danced on them. (40)

Godfrey notes the freedom explicit to certain feminine expressions, recontextualising them to show both their limitations and liberatory nature. As well, they highlight the clear limits of power in a society constructed around patriarchy, even when an idea, at first, seems like liberation or revolution. This, in effect, foreshadows Part Two of the collection, ‘the femme fatale goes home,’ which blurs the boundaries between self, other, and object, as Godfrey, too, blurs the line between housemate, intruder, myth, and mirror-image, perhaps in search of a weaponised protector. They write:

She has filled the space with something unworldly, something unspeakable, something soaked and aching and entirely hers. The room responds to her presence like a lava lamp to touch. One of her legs is bent, foot raised, her toes grip the porcelain lip. Her body folded in half, an angle so awkward it could only exist in a fashion magazine. Her body resembles a body in a fogged-up mirror. (43)

In this compartmentalisation of self, in this creating of apparitions, Godfrey queries the feminine powerhouse, as it washes the dishes, goes out partying, offers up confessionals through burps: “What purpose would a throat have, if not an elite room that men can enter? If a woman is a speakeasy, who decides the password?” (‘The Femme Fatale Goes Home,’ 51). Overall, Godfrey challenges the role of the Femme Fatale, moving her from paper thin, escapist concoction – or perhaps agent of the male gaze – and turning them into a Femme Menace, who “teaches [them] how to be a menace to everyone other than myself” (‘Femme Menace As Guardian,’ 62).

In Part 3, Godfrey redirects their gaze back to the gender binary, and the evident disconnects they feel for a feminine self – or, perhaps, more accurately, a former self. And yet, too, there is a sense of unbridled longing that permeates almost every line, as if the subject has already committed themselves to the learnings of the Femme Menace – a perpetual dissolving of genders that sees them neither here nor there but, rather, now.

A lot of the collection, in its unrelenting self-excavation, in its surrealist, camp, sometimes brash, often sarcastic tone, coupled with its perpetually evolving, self-referential social commentary, speaks to poets like Virginia Lockwood and Chelsey Minnis. Minnis was once described by poet and publisher Sam Riviere as a “purveyor of an enhanced, mordant femininity, recording the simultaneous disintegration and amplification of glamour as it enters a disaster zone, ‘a shimmer like sequins flushing down the toilet’, through an unequalled abundance of decadent, obscene, renunciatory images.”

Too, I’d be remiss not to mention local writers like Eloise Grills, Holly Isemonger, Alex Creece, and Dan Hogan – poets who poke at the margins of gender (and so much more) through humour, through the sardonic, through the absurd and obscene. And yet, despite these glowing cotemporary examples, I’m reminded that in the history of Australian poetry there’s never been much time for work like Godfrey’s, not just in terms of representation – a point made throughout – but also in creative exploration, in humour and hyperbole and sheer literary decadence. Sadly, many poetry lovers and advocates will admonish work that is funny, wry, or overtly self-celebratory, particularly when it comes from someone we’re cultured on the Left into seeing as a serious ‘identity.’ But humorous glamour in its myriad forms is the elevator key, as it allows us to view multiple and sometimes conflicting positionalities, sharply extracted through deft tonal transitions and overtly layered whimsy.

And here lies the true brilliance, perhaps even genius of Godfrey’s collection: it isn’t just a work of spritely lyricism and deep insight – it is actually funny and joyful as all get out.