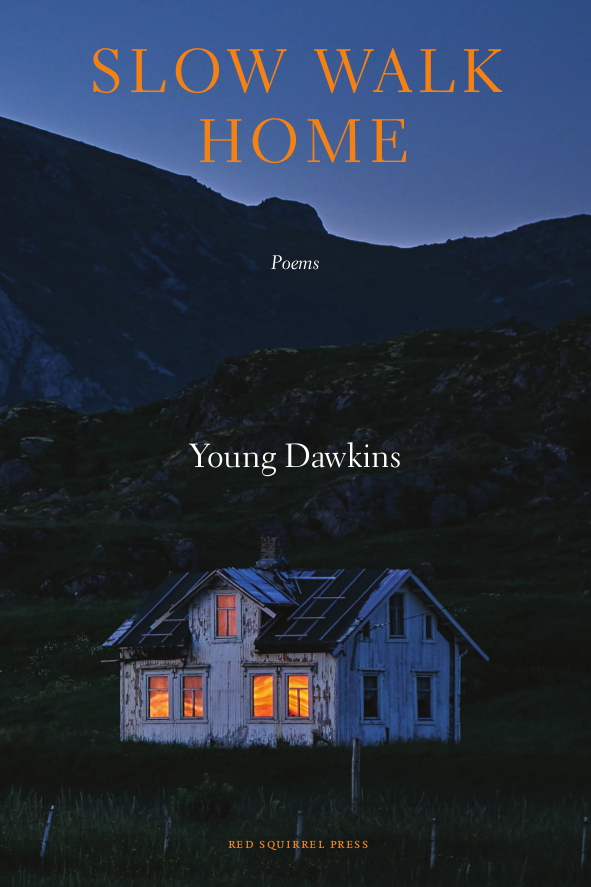

Slow Walk Home by Young Dawkins

Slow Walk Home by Young Dawkins

Red Squirrel Press, 2021

There is a humour to Slow Walk Home that interrupts solemn atmospheres with a wry warmth, comedy and tragedy unfurling like contrasting petals of the same bloom. The second collection of verse by Young Dawkins, an American-born poet who has lived in Scotland and now resides in Tasmania, Slow Walk Home also pays homage to Beat poets of his generation, evident in poems such as ‘The Real Lion—Ginsberg’ and ‘Kerouac, Raton Canyon’. But these homages aren’t mere nostalgia – Dawkins offers a glimpse of the era through a fractured looking glass, not entirely rose-tinted, but perhaps with a smudge of its glow. In ‘Fishing with the Dead’ and ‘Breakdown,’ Dawkins tempers his reflections on the past with a mature gaze – both poems inhabit a quiet sense of finitude, but not melancholy, as the speaker witnesses a collapse in communication. There is a sense of arrival approaching acceptance as the latter poem’s final line reads: ‘The railroads are dying.’ This poem powerfully conveys the bewildering sense of love’s failure in one becoming unknown to the other, an experience illustrated by weeds devouring machinery: ‘Swallows are nesting / in the faded / yellow coach car / that was our love.’ In the yellow coach car, Dawkins shows the wild ache of abandon, the lost capacity for warmth that emanates from a hollowed vessel of memory. As Dawkins writes in ‘Portsmouth’, ‘Memory is the diamond stone / on which we hone our edges.’ These are not so much trips down memory lane as an observation of memory’s physicality – the ways in which life is contoured by loss and mortality, evoked in decomposing symbols of the old American dream: hollowed-out cars, railroads that come to an end through their disuse.

In his encounters with dead ends and cul-de-sacs, Dawkins acknowledges that, to parrot a simple adage, that all things, good or bad, must pass. In doing so, he draws connections between homage and transience. Among the references to other poets of his generation is a sense of memory as a fluid instrument, filtering through channels of music and image to find a place of rest. The act of remembering and paying respects to loved ones passed is expressed in the simple practice of walking. When the speaker goes to visit the grave of a loved one, or crosses the road, these sites are rendered at once surreal and mundane by glimmers of reverence and humour.

Maybe it’s the old Billy Connolly rule that you can make anything funny with a Scottish accent, but reading ‘Green Man’ made me laugh out loud at the poem’s deadpan line: ‘you cannae / simply stand there like some fucking tourist.’ Dawkins wields humour in different ways throughout – it intercepts tragedy in the poem ‘Dialogue’, where the speaker visits their father’s grave in a cemetery, all the while recognising the names on other headstones of people they knew growing up. The grieving speaker sits down in the cemetery:

I said, Dad, I love you. I miss you. He was silent. I took one of my business cards and placed it above his name, in case he changes his mind.

These poems are deceptively simple in narrative, but they hold a balance between seemingly conflicting forces. In bringing together these glimpses of humour alongside stretches of sorrow, Slow Walk Home reads like a tapestry of love and loss. The warm joys of the mundane are interspersed between dizzying highs and punishing lows. For example, Dawkins’ poetry trammels the small pleasures of everyday routines with subtly evocative language, in the poem ‘The Perfect Chicken Sandwich’ (‘toasted fast beneath an angry grill’) and the poem about his son, ‘Tom, One Year’. This poem is as guileless as its title, but playful in its depiction of parenthood:

we throw stale bread at indifferent ducks, then bundle back home for a later lunch of pasta, self-served by fat little fingers.

The rhythm of these poems works alongside images of food and contented repetition, creating a sense of comfort, or the radiance of quiet happiness.

Not ready for sleep and too early to eat— we walk around the flat, you crooked in my arm, and together we put names to the mysteries; Door. Clock. Rug. Light.

But there are sections where the poetry feels perhaps too satisfied, too convinced of its own enclosing logic, such as in the closing poem ‘Home’:

they sent a beautiful woman from the edge of the earth, first to hold me, to love me, to remind me of being a man.

The poem doesn’t make it clear if the implication that women are put on earth to remind men of their masculinity is intended as wryness or irony that emerges in the rest of the collection, or whether it is an unintentionally earnest cliché. Either way, to end with something so conclusive (or so loaded with irony) feels like a missed mark for in a collection that is otherwise adept at unravelling more complex expressions of relationships. Either way, the entire poem feels as if it is trying to bundle an expansive allegory into a few universalising words that could be deliberately ambiguous, but which lack the specificity and depth of the preceding poems.