TM: I still remember the first time I visited your studio in Brunswick at the end of 2019, and you were beginning to use Jennifer’s words in your paintings. And it’s something I’ve wanted to ask for some time, but how emotional was that for you? You’ve taken language in such conceptual directions now, but early on we talked a lot about that Sutton show, and the links between love, grief, care and art. Was it perhaps a way of connecting to your mother? And even thinking about how you’re copying words written by your mother onto a canvas with paint – is there something deeper in that repetition?

DBA: I think there must be. I have consciously tried to use personal experience to speak to broader themes, to open it up, but the essence is emotional and deeply felt. A friend Micky Schubert mentioned a quote to me after my last exhibition, A Measure of Disorder: ‘After great pain, a formal feeling comes’ by Emily Dickinson, which I thought was wonderful and probably spot on.

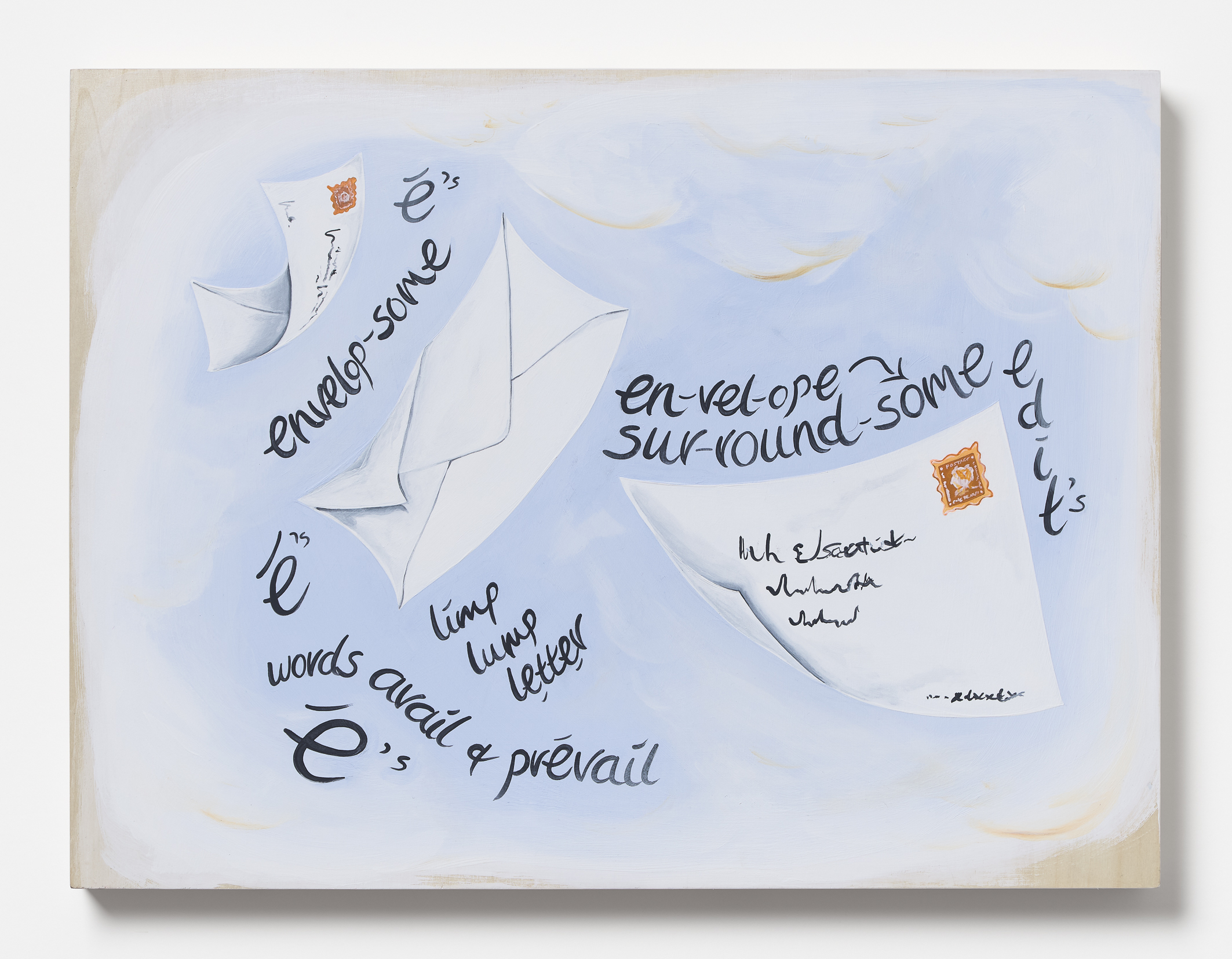

TM: You capture the movement of words so vividly. Like in your Note Paintings, 2020, Jennifer’s words associated with letter communication are given a sense of travel, of flying of words through time and space:

Darcey Bella Arnold, Limp lump letter, 2020, 46 x 61cm, acrylic on board. Courtesy Darcey Bella Arnold and ReadingRoom, Naarm/Melbourne.

Can you talk through the process of animating these words, giving them a visual representation that speaks to their context?

DBA: I made these Note Paintings during the Covid restrictions when I was unable to see Jennifer, a difficult period during 2020, as a way of checking in with each other. Jennifer would write me little notes each day and I painted four or five of them. I was really playing with form and text, having fun with it, and not thinking of an outcome for these works. Thinking of Emily Dickinson again, I had her poems beautifully written on envelopes in mind when making these.

TM: To skip forward to some recent works, can we talk about the below work and what’s happening in this image:

Darcey Bella Arnold, ceci n’est pas une, orange, 2022, oil on cotton duck, 80 x 90cm, saffron, acrylic on cotton duck, 150 x 200 cm and American Red Oak stand. Courtesy Darcey Bella Arnold and ReadingRoom, Naarm/Melbourne.

The French writing of course immediately recalls René Magritte and his The Treachery of Images, or better known as ‘this is not a pipe’ (I love that idea of treachery!). But it’s also pointing out the truth of language – this really isn’t an orange. How do you conceive of the relationships between art, object and meaning?

DBA: In this work I am really trying to point out the fallibility of language. By taking Rene Magritte’s joke, ‘this is not a pipe’, and replacing it with an orange: ‘this is not an orange’. Recently, I have decided to place parameters on the elements in my making, using orange as a dominant colour. The colour orange is named after the fruit orange, and so thinking about language, a thing and its name have a totally arbitrary relationship.

In Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, the language in the painting is the authority, the pictorial image is of a pipe, then the sentence denies the image. The image is trying to trick you, but it is not a real pipe, it is a painting. But the word ‘pipe’ is not a pipe either, it is the signifier to the pipe the signified. Signified (thought). Signifier (sound). This relates to Jennifer, who believes in the authority of language, above images, above representations.

As a tactic at home we would put signs up in text saying, ‘this is your home’, and she would believe it. She would believe it more than when we spoke those words to her, the authority of the written word is above all else. So, if it says: ‘this is not a pipe’, then ‘this is not a pipe’ is believed. But of course, it is a pipe. It is how we learn what a pipe is, so it is questioning that authority. It is nonsense, it pulls apart ‘the rules’ which is what Jennifer does.

This is not a pipe is really pointing out the failure of language. Ask anyone what that image is, and they will say ‘a pipe’, as we have been taught. This is our education: children’s books are designed to teach language. They do not say: ‘this is a picture of a cat’ to teach the word cat, or this is the word ‘cat’ next to an illustration/representation of a cat, it just says ‘cat’.

The painting here, ceci n’est pas une orange (this is not an orange), works to affirm the authority and arbitrary nature of language. Adding another layer to Magritte’s joke, the colour orange and the fruit orange use the same word, so we have three ways to communicate/comprehend orange: the idea of the fruit (signified), and the idea of the colour (signified) the word/sound (signifier). Orange (word). Orange (fruit). Orange (colour).

TM: That so beautifully explains the fallibility of language as a descriptive device for the world. A version of this work also featured in your 2022 exhibition, A Measure of Disorder at Gertrude Glasshouse, where you created a series of paintings, some with text, others centering orange, and the repeated motif of a comical, running clockface. The starting point were two words, atrophy and entropy, which Jennifer uses as placeholder words. Can you explain how a body of work arose from this?

DBA: The words atrophy and entropy are two of Jennifer’s favourites, which she uses daily in verbal and written communication. Her use of them is unconventional and the best way to describe it, I think, is that she uses them as placeholder words and so they can have varying meanings depending on context, however the use of them is overwhelmingly positive. I have always thought it very interesting that a person with a brain injury, such as Jennifer’s, would be interested in these two words. Atrophy and entropy are not dissimilar, atrophy being the breakdown of muscle and entropy is the second law of thermodynamics, which states that order becomes disorder, all things will break down. That disorder, characterised as a quantity known as entropy, always increases. I took these two words and followed them around researching the languages surrounding them, which included infographics, chemistry, science, and art history. Entropy requires the passage of time, which is where the clocks came to the project, also linking this to art history and my interest in Phillip Guston.