For Martinican poet and theorist Édouard Glissant, forced poetics exists ‘where a need for expression confronts an inability to achieve expression.’1 Glissant further clarifies this when he argues that ‘a forced poetics is created from the awareness of the oppositions between a language that one uses and a form of expression that one needs.’2 For Lionel Fogarty, the divide between what is said and what goes unsaid, between Indigenous life and non-Indigenous assertions, exemplifies this pressure, poetically and politically. The tension which exists in this collection is a continuance of the struggle for self-determination and for justice which have typified Fogarty’s writing for the last thirty-five years. These poems represent the struggle for the right to be able to tell one’s own stories, as the poem ‘Fuck Off’ argues:

Deep down in the black anthropological mind lives an historical process you all here never will re-write.3

In that the language of this collection is seen to contravene the grammatical and syntactical constraints of English language usage, speaks to the ‘forced transculturation’ of non-Indigenous language and culture in the telling of Indigenous history. That same tension underlies many of the poems contained here, where corporate and / or government words ‘Reinforce white dominance’ with a ‘syntax blotched (by) greed.’ The division between rurality and rusticism is played upon in the heart-breaking poem of post-mining boom small towns ‘SEE SEA OVER DEWS IN CEDUNA’, just as the divide between Aboriginal reality and labour and the saleability of Aboriginality is fiercely critiqued within the collection. Continuing from ‘Digger lion’s goal’, the line ‘Revitalizing extraction’ unfolds into ‘Sacred histories severed on impacted reclamation’. ‘Revitalizing extraction’ levels accusations at (foreign owned?) corporations for the extraction economies of resources and culture; at once a boutique multicultural project (with their Indigenous employment targets and job incentives) the devastating ecological and ontological effects which Indigenous communities are often left to bear. That ‘Sacred histories’ are ‘severed’ and ‘dispossessed’ speaks of derivations of value and labour, and sets up a dialectic between surplus value and surplus lives. Everyday language, especially that used for corporate control of Indigenous Country, is represented as corrupt and corrupting. This is language which needs to be broken, to be disseminated and retooled. What Fogarty presents in this collection is a language which has been recalibrated, which reflects the linguistic corruption it is exposed to and which speaks with historical horizons far longer than any market projections.

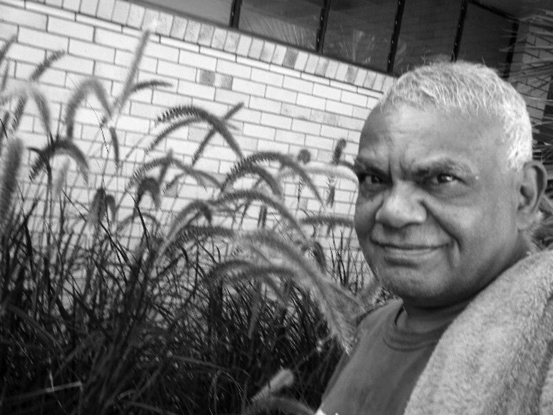

Lionel Fogarty: No Cites like the Cites Hum In

Lionel Fogarty: Conquer Slaughter’s

Lionel Fogarty: Never Worked

Lionel Fogarty: See Sea Over Dews in Cenduna

Lionel Fogarty: Yo I Am the Man

Lionel Fogarty: Cops are poets on the looks sit hears cobs

Adding to the multifaceted attack on linguistic and cultural expression, is the status and functions of possessives within the collection. The challenge to definitions of ownership and the very constructs of personhood are contested within these agrammatical examples, ‘cities are built on times land.’ Here, time is given in identificatory language, as governing and possessive, but also as reflecting a plurality of temporal fields (mythopoeic, colonial and authorial times) and as possibly as establishing hierarchies of control and dominance, where ‘Homeland is earth’s lust’. The complications of personal identity and identifiers are as complex as antecedents we can trace to the Black Arts Movement.4 The criticism latent in a ‘Were are the many stars’ problematises historical categorisations of Indigenous Australians (‘were’) and doubly, or perhaps exponentially, problematises the relationship between those Aboriginal Australians being defined and their capacity for agency and decisive action given in the corruption of the verb ‘we’re’. In even this most subtle way – and Fogarty’s poems are not typified by their subtlety – the poems in this collection critique the concept that Indigenous lives are qualifiable, and stand against the impact of language in over-determining the confines and constructs of Indigenous life.

It is with this caustic approach that Fogarty contests the political future of reclamation, of sanctity and of self-determination. It is a position from where he determinedly stakes a claim on the stories that lie at the heart of the country.

Pingback: Reading at Double-launch event for Candy Royalle’s collection and Australian Poetry Journal 8.2 | pascalle burton