Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski

Justice for Romeo, as a title, will seem both accurate and misleading for most readers; this is a book decidedly concerned with justice, and Siobhan Hodge’s sense of ethical responsibility pervades the poems. Hodge’s book includes as epigraph the exchange between Romeo and a servant in Act I, Scene ii of the most famous love story of all time; the servant asks, ‘I pray, can you read any thing you see?’, to which Romeo replies, ‘Ay, if I know the letters and the language.’ This epigraph has significance for the whole poetry collection, since Shakespeare’s play is as much about blind hatred as it is about love; Romeo’s reading the letter immediately after this exchange begins the tragedy.

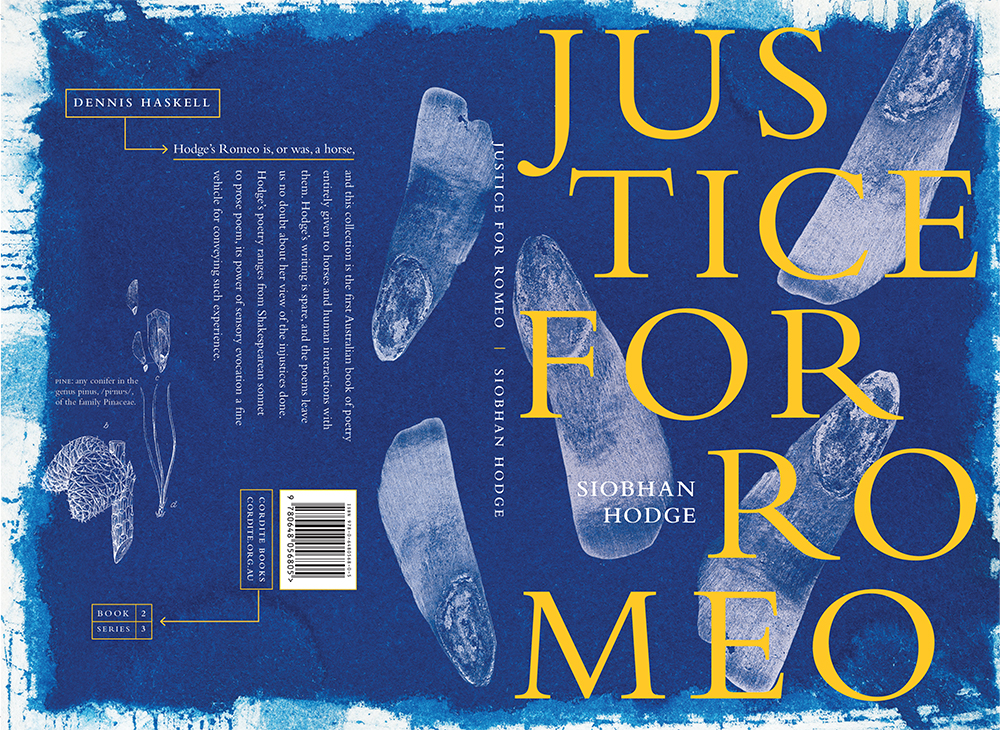

However, we are misreading when we rush to identify Hodge’s title with Shakespeare’s character. For Hodge’s Romeo is, or was, a horse, and this collection is the first Australian book of poetry entirely given to horses and human interactions with them. Horses have been domesticated since 4000 BCE and the book is centrally concerned with the way that domestication occurs and is maintained.

The opening epigraph instructs, ‘The rider should know his horse physically as well as mentally … to understand his feelings and anticipate his reactions’. Hodge’s searching and heartfelt meditations show that this is true but glib; she does attempt empathy in the poems, but recognises that sympathy is as far as she, or any human, can go. Horses feel, think, see and react differently to us, and Justice for Romeo is an appeal to respect their independence and right to being. The second epigraph says, ‘It is best to let the horse go his way, and pretend it is yours’. We live in a period when the human capacity for empathy and sympathy with the other, not only with animals but immigrants, refugees and the planet itself, seems in short supply; this only serves to emphasise the importance of what these poems are attempting.

While Hodge’s writing is spare and dispassionate in tone, the poems leave us no doubt about her view of the injustices done to horses: for money through racing, for work and their treatment as machines, for war, ‘teeth … poised / for battle’, and sometimes even for art. Hodge’s own stance contrasts with a history of human arrogance but she is a skilful enough writer that her judgements are embedded in the poems.

Poetry, with its power of sensory evocation, is a fine vehicle for conveying such thought and experience, and Hodge’s poetic forms range from Shakespearean sonnet to prose poem. When riding, she and the horse are very much part of nature but when, for example in the poem ‘In the Pines’, she and the horse fall or approach a poisonous dugite snake, nature is not sentimentalised. These are poems which show not just knowledge and admiration for extraordinary creatures – that is, horses, not people – but a mature acceptance of the world as it is. Even Hodge’s accidents with horses recounted in ‘Bone Binds’ are evoked without bitterness as ‘aerial / lift’ with ‘Air kinder / than ground’.

Hodge’s poems give the horses’ ‘throttled tongues’ some voice, eradicating a ‘curriculum of silence’ but in our letters and language, so that the poems tell us about human imagination, fear, wish for power and concern with beauty. She has a greater variety of rhythms than The Man from Snowy River, so ride along with her: ‘in this mess we’re together’.