I was even gratified to see that John Darling’s test scores were far worse than mine, and I stopped speaking to him soon after the teacher called him to the front of the classroom for a public dressing down. I actually felt a fair bit of satisfaction from it – John and his siblings may get to have fun and adventures with that fantastical ‘boy in green’, but I have my good test scores. Something real.

Squinty-eyed, long-nosed trolls at the end of rainbow bridges, chewing and spitting out the dreams of little children. Guarding that elusive pot of gold from us all.

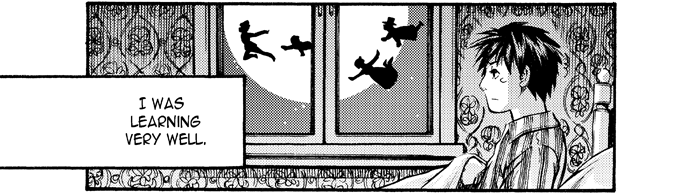

I spoke no more of the Darlings, or of that ‘boy in green’ to my father or grandmother.

‘Son, I am proud of you’, he said.

I was so surprised I stopped counting the number of men in grey bowler hats walking past our house. My father was a quiet man, and the few moments we were able to steal from my grandmother’s prying eyes were spent mostly in peace and silence. As of now, we were sitting on the steps at the front of our house, a sometime ritual of ours, since my grandmother’s disapproving gaze can fill the whole house with a heavy presence. My grandmother did not like idleness.

I looked up at my father, expecting him to be looking back at me, but he just gazed at the endless hustle and bustle of Kensington. We lived close to Kensington Gardens, and at that time of the day, there was non-stop foot traffic going to and fro.

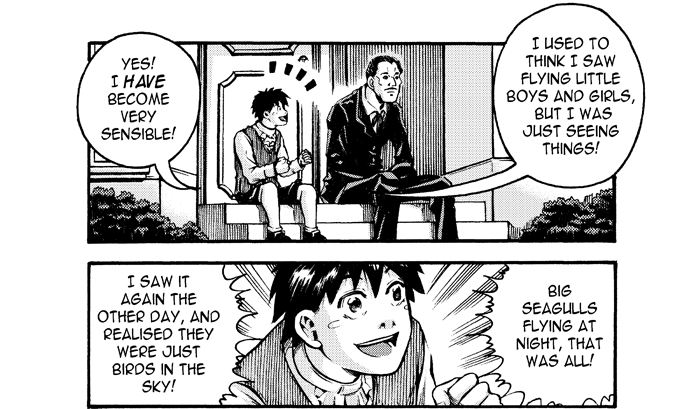

My father continued. ‘At the time, I was corrected by my betters, and I became a sensible young boy. I was very grateful for that. I stopped seeing these … things. I understand that you are also, however slowly, becoming a sensible Pickwick too.’

I gasped, and my heart leapt high at the compliment. Compliments do not flow easily in my household, and I felt a warm swelling of pride, bubbling up from deep within. At last, at long last! My father acknowledges that I am a Pickwick too! My mother, bless her heart, would be so proud!

Eager to prove my newfound membership, I blurted out the first thought that sprang to mind.

This was wrong. It felt wrong. I had said something, and now my father was gone – flown away like he sometimes did, whether he was sitting on the armchair with his pipe, or staring out the window at the sights of Kensington. What did I say?

I tried to search his profile for a sign, but he was now far, far away, and cannot be reached. Perhaps he will come back if he finds what he is looking for, but given how often he gets that look in his eyes, he has made countless trips and has never found it.

‘That’s good’ he eventually murmured, but he said no more after that. We just sat there on the stairs, until it was time for dinner.