All was going well, until one morning.

Those malicious jack-in-the-boxes sprang up first, leering smiles on their twisted faces. ‘She didn’t fall … she didn’t fall …’ they whispered over and over.

‘She had enough of life, and so she leapt …’

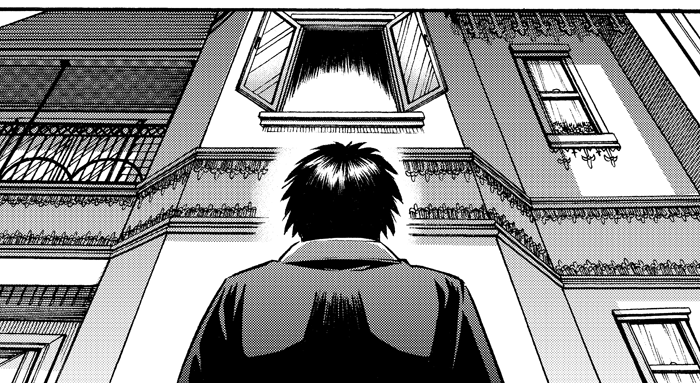

Of course! Why didn’t I notice? My grandmother had died right outside her bedroom window, a small detail back then, but the only plausible explanation right now. My grandmother’s bedroom was on the second floor, and her window faced the same direction as mine. At the time of her death, her window was wide open – a strange fact, given the chilly spring air.

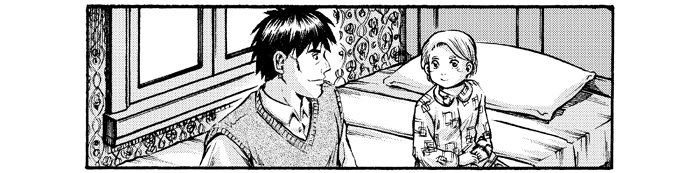

Her room has long since been Father’s room, though he rarely mentioned anything about it. Perhaps it was futile to expect him to – for my father, the one who used to be so sensible, had in his later years become an old man who barely said a word. He would sometimes stand on our front lawn in the cold spring night, staring up at the stars and muttering in a language only he could understand. When that happened, barely anything could be done to coax him back inside the house. He was gone, flown away with that faraway look in his eyes, a look that stayed longer and longer as the years went by.

Whatever he was looking for just over that horizon, he has finally found it.

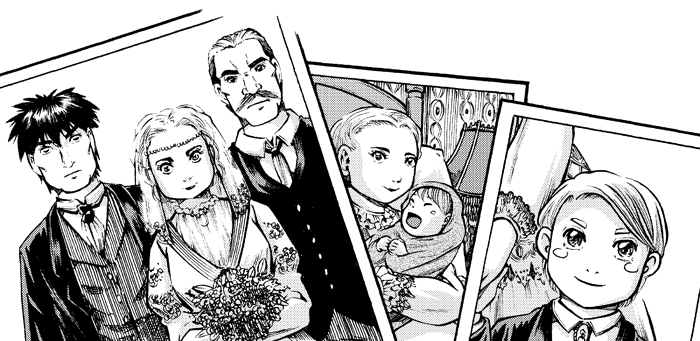

My heart ached, and I shook my head slowly, as a burning sensation came to my eyes. So much did I lose. Not just Father and Grandmother. As I stood over the frozen body, I feared to look up. I feared the mermaids, the pirates, the adventures, and the ‘boy in green’; but most of all, I feared that pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, even if the trolls who guarded it were all dead.