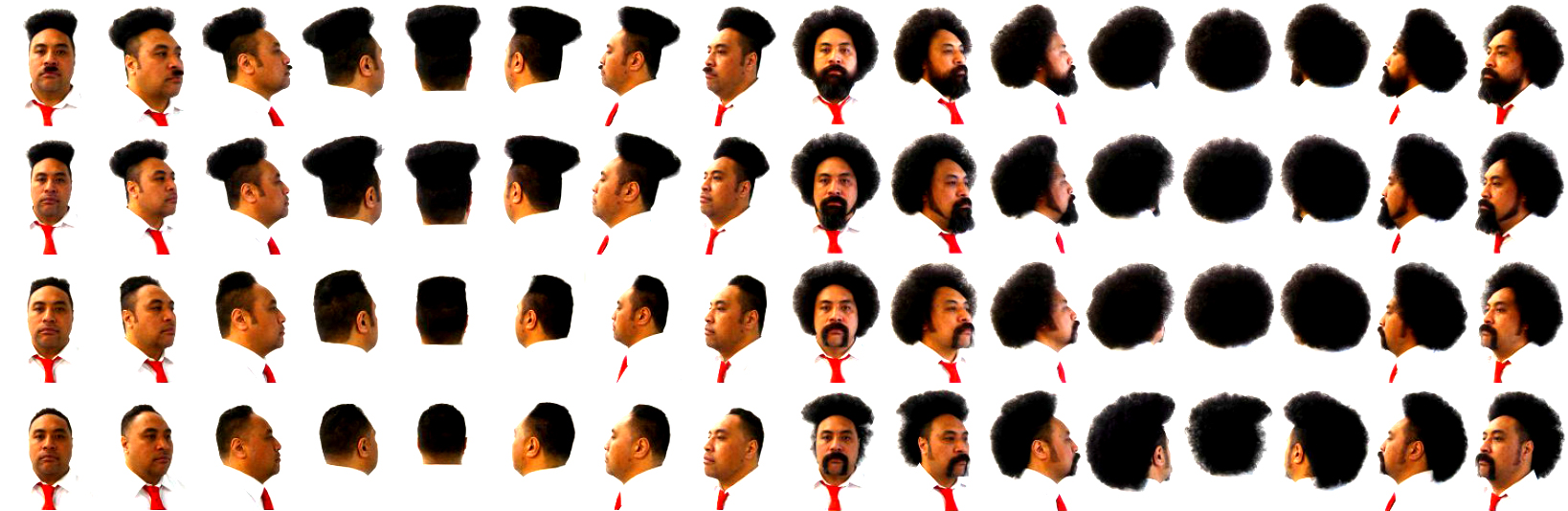

Siliga David Setoga | Oki fa’a kama Samoa moni lou ulu / Cut your hair like a true Samoan boy | 2015

Photograph: Setoga Setoga II | Barber: Maligi Junior Evile>

E kore au e ngaro; te kākano i ruia mai i Rangiātea

I will never be lost; the seed which was sown from Rangiātea.1 This poetic saying refers to Māori descent from Polynesia, specifically the island of Ra’iatea in the Tahitian island group.

I was asked by Kent MacCarter to edit a group of indigenous poems from New Zealand. I have chosen to include Pasifika poets who are related to Māori through shared ancestry reaching back thousands of years into the South Pacific, and who are resident in Aotearoa. That is not the usual definition of ‘indigenous’ which would normally refer to peoples who are colonised within their homelands and who are now governed as a minority group, but it is a normal relationship to group Māori and Pasifika poets given our shared colonial histories (only Tonga was not colonised) as British subjects.

Two Anglophone poetry anthologies I co-edited with Albert Wendt and Reina Whaitiri, Whetu Moana and Mauri Ola, included Polynesian poets living inside and outside Oceania ranging from Aotearoa, to Samoa, Hawai’i, California, Oregon, London and Dubai. I hope that this brief selection arouses interest in new Pacific writing in Australia which has a growing Polynesian diaspora of its own.

I did not group the selection thematically. Each poem was chosen because I found the poem engaged me either emotionally; as a dance of the intellect or ideologically. In short, there is no singular way of writing as a person of indigenous descent.

Apirana Taylor: Mountains

Apirana Taylor: Why

David Eggleton: Spidermoon

Jacqueline Carter: When We Went to Brisbane

Kiri Piahana-Wong: Falling

Marino Blank: Bronte to Bondi

Reihana Robinson: BREAK ALL MY BONES …

Robert Sullivan: Long Light

Serie Barford’s contribution begins right at birth, yet the opening image is a death one – the pine on Auckland’s One Tree Hill stood next to the monument to the Māori people erected as a memorial for the race. The tree was later damaged irreparably with a chainsaw by Māori activist, Mike Smith. Apirana Taylor’s poems also bear the scars of war, and invoke myths of mountains in fits of jealous rage. David Eggleton’s ‘Spidermoon’ is a lush sensory scape where all five senses are enlivened by the newness and the strangeness of the narrator’s visit to Mount Chincogan in northern New South Wales. Jacqueline Carter’s poem is also an Australian encounter, but this one desires a true meeting with Koori rather than the emptiness of tourist areas. Amber Esau invigorates a traditional Samoan dance with love poetry. Kiri Piahana-Wong in ‘Falling’ addresses identity as a meditation on absence. Marino Blank describes an urban Bondi Beach scene without naming her point of view as indigenous or even Māori, and yet so many Māori have emigrated there it becomes a particularly Māori and Australian poem. Reihana Robinson cites the singer songwriter Mia Doi Todd in a poem that speaks of a relationship in flux.

This range of poems is a microcosm of Polynesian poetry in English with its abundant personal themes, place-based writing, natural and contemporary referents, simultaneously globalised, sassy and politically motivated by a sovereign past. Each poet adopts different stances to identity, culture, sovereignty, environmentalism and their other significant relationships. They are writing about the human condition.

- Mead, Hirini Moko, and Neil Grove. Ngā Pēpeha a ngā Tīpuna: the sayings of the ancestors. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2001. ↩