Adaptation or Theft? Li Bai and Ezra Pound

The works of Chinese poet Li Bai (701-762), also known as Li Po, were the focal subject of Ezra Pound’s Cathay, published in 1915. This particular translation has attracted much criticism from Sinologists for its gratuitous infidelity to the original material, though the poetic qualities of the rendered versions have seldom been have never been in doubt. Ming Xie observes that Pound’s translation, among others produced by Anglo-American writers, can be considered a form of assimilation:

it is possible now, retrospectively, to recognise how these Anglo-American writers had construed and appropriated certain aspects of classical Chinese poetry according to their own preconceptions and creative needs. Yet when the results of such translation or adaptation are successful English poems in their own right, it is often tempting to assume that they are in fact closely and directly derived from their Chinese models.1

Cathay represents another crucial factor in giving more credence to the role of the translator in the production of a text; without clear acknowledgement of where the actions and decisions of the translator come into effect, particularly adaptive translations risk being considered acts of colonising or dominating another text.

Creative adaptation involves a measure of individual engagement that needs to be clearly recognised, rather than projected as part of the original writer’s oeuvre, or depicted as wholly the work of the translator. Xie remarks that in Pound’s poetic oeuvre ‘it is often difficult to distinguish between what is translation or adaptation and what is original composition. For Pound there seems to be no fundamental distinction between the two.’2 Such an all-encompassing approach ought to be handled with greater sensitivity by modern translators, if it is to be adopted; Pound’s translation is dynamic to the point of appearing to be only inspired by images or themes within the original poem, rather than reproducing Li Bai’s work. The creative adaptor in this instance is almost entirely operating as a poet, with only cursory references to the text allegedly in translation.

This can, in part, be attributed to the mode in which Pound accessed Li Bai’s work: via a series of comments in Ernest Fenollosa’s notes. Pound produced Cathay after reading a series of translations, notes, and English translations of other Chinese poets produced by James Legge and Herbert Giles around the same time period, rather than approaching the original Chinese text directly.3 Li Bai’s poetry was never the sole point of access for Pound, which may also account for his distance from the original poems, and may also thematically connect to his decision to remain removed from these. Pound the creative adaptor is operating almost entirely as a creative agent, with only a cursory acknowledgement of translation as his medium, in keeping with his own removal from both Li Bai and the producers of the texts he has accessed. It is also possible that the translations Pound examined were not entire, making it even more equally that Pound consciously departed from these to capture what he perceived to be the core focus of each poem, and to recognise the distance between himself and the poet, revealed and emphasised by his complex route of access. Hugh Kenner assesses Pound’s translation as essentially ‘stating the ‘image’ exactly and then leaving it alone to do its work,’ which would further emphasise this divide between poet and translator, and the transition to poet-translator, adapting material almost past the point of recognition.4 Pound’s Cathay reads not only as a thematically-driven translation, but also as a reflection on and perhaps even as a subtle criticism of the nature of poetic transmission through translation.

According to Xie, two primary theories from Fenollosa’s notes, Pound’s key access point to Li Bai’s work, may have encouraged the poet to adopt his exceptionally dynamic ‘translation’ process:

Firstly, the Chinese ideogram is metaphorical, not abstract, since the ideogram is composed of concrete things and vivid pictures. Secondly, the Chinese sentence, made up of such ideograms, represents the processes and operations of nature; it denotes a ‘verbal idea of action’ and a transference of energy. This verbal action involves the perception of dynamic relations in process. Taken together these two emphases are directly opposed to what Fenollosa (and Pound) took to be the characteristic Western habit of abstraction.5

Pound clearly engages with the imagism of ideograms in Cathay, but his exceptionally dynamic translation also indicates the ‘verbal idea of action’ encompassed in the source text’s characters. Pound engages with Li Bai with a dynamism propelled by research and poetic inspiration, generating a text that reflects Pound’s experiences as a reader of Li Bai only via translation, and engages in a poetic dialogue with the source texts and later critical commentaries. Pound does not set out to simply replicate Li Bai’s work in English, but to reflect on processes of dynamically reading translation, engaging with the original text in new forms. Consequently, though issues of assimilation cannot be completely dismissed, Pound’s Cathay as a creative adaptation of Li Bai’s work still offers much material for consideration from a translation perspective.

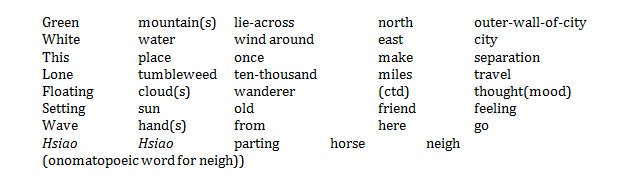

Pound navigates Li Bai’s work with a close focus on thematic content and imagery, but does not strictly replicate either. For example, in the poem ‘Taking Leave of a Friend’, Li Bai depicts an emotionally-charged departure for two old friends, set against a mountainous background. Wai-Lim Yip translates the poem literally, reproducing Li Bai’s original line structures below:

6

6The piece is tightly regulated into eight lines and five columns, reflecting the structural considerations of traditional Chinese poetry. Each column contains only one Chinese character, all of which operate as entire words, except for one word which requires two, breaking Li Bai’s prescribed pattern. The word in question translates to ‘wanderer’, which is a particularly appropriate decision in light of the poem’s content. This subtle breakage in structure, via a single two-part word, emphasises the distress of human departure explored in the poem, linking the poem’s thematic focus with its prosody. In Cathay, Pound opts for a more familiar poetic structure and focuses more strongly on the emotions and scenery permeating the scene, in accordance with his Imagist beliefs:

Blue mountains to the north of the walls, White river winding about them; Here we must make separation And go out through a thousand miles of dead grass. Mind like a floating white cloud, Sunset like the parting of old acquaintances Who bow over their clasped hands at a distance. Our horses neigh to each other as we are departing.7

Pound’s rendering of the poem is powerful, and its imagery generally faithful to Li Bai’s original scene, but the focus has shifted and the original structure lost, along with the subtle ‘wanderer’ manipulations. A compromise could be made by printing Li Bai’s original poem alongside Pound’s rendition, offering basis for comparison, as well as a translation key that acknowledges Li Bai’s innovations within the piece, but that would not necessarily serve Pound’s broader creative project. Rather than being a delicate translation, Cathay reads as an exploration of the implications of distance from a translation, language, poet, and field of critical thinking. Pound’s ‘Taking Leave of a Friend’ is no less poetically adept or striking than Li Bai’s, but to present this poem as a direct translation is to misattribute both poets’ works and to detract from the intentions of both. The individuality of Pound’s experience in reading Li Bai has been layered over the original poems’ structures and linguistic content, assessing the nature of translation rather than the original text.

While modern translators may be loathe to engage with quite the same level of manipulation as Pound, particularly from a more culturally sensitive perspective, the value of Pound’s Cathay as both a creative adaptation and an individual reflection should not be dismissed. Though far less subtle than Kiyo Niikuni’s translation style, Pound’s approach clearly denotes the importance of the translator’s own views and experiences in rendering a text for consumption by another audience, and invites personal engagements and further research in a much more pervasive way.

- Ming Xie, Ezra Pound and the Appropriation of Chinese Poetry: Cathay, Translation, and Imagism, New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc., 1999, p. 3. ↩

- Xie, Ezra Pound and the Appropriation of Chinese Poetry, p. 229. ↩

- The Fenollosa notes refer to Ernest Fenollosa, ‘The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry’ (edited by Ezra Pound), London: Stanley Nott, 1936. ↩

- Hugh Kenner, The Poetry of Ezra Pound (reprint) , USA: University of Nebraska Press, 1951, pp. 187-188. ↩

- Ernest Fenollosa quoted by Xie, Ezra Pound and the Appropriation of Chinese Poetry, p. 236. ↩

- Wai-Lim Yipp, Ezra Pound’s Cathay, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969, pp. 12-13. ↩

- Ezra Pound, Cathay: Translations by Ezra Pound for the Most Part from the Chinese of Rihaku, from the Notes of the Late Ernest Fenollosa, and the Decipherings of the Professors Mori and Ariga, London: Elkin Mathews, 1915. ↩