Cinematism

Philip Mead begins his study of Australian poetry, Networked Language, with a chapter dedicated to the significance of Slessor’s work as a film critic for understanding the modernist poetry he wrote during the interwar years. Mead relies on a term proposed by critic and BBC Radio producer Philip French in the 1990s to make this link. ‘Cinematism,’ according to French, captures the poetic content of cinematic time (35). Yet the links between the actual cinema and the writers of Australia’s modernist verse, Mead writes in 2008, coalesce around the broader context in which he recounts the complex entanglement of the technologies of moving images operating alongside modernist giants such as Joyce and T S Eliot. Imagism in the era of the First World War responded to the mechanical utility of life with the ‘return of the real’ becoming a strange index of the new type of technical humanism that came after it. Subsequently, the idea of cinematic time, or a film age, has continued to be propagated by post-structural theorists such as Mary Ann Doane and Bernard Stiegler, which follows on from the earlier work of European critical theorists relying on Marxist analyses of history, such as where undertaken by Hungarian sociologist and art historian, Arnold Hauser.

In The Social History of Art, Hauser writes that in the ‘intermingling of temporal and spatial forms of the film,’ the ‘strands of the texture which form the stuff of modern art converge’ to form a ‘new conception of time’. Given the novelty of this conditioning for history, Hauser claims that ‘differentiating and defining the media’ in which culture is encoded becomes impossible (226). Unsurprisingly, because of this confusion the cinema became the most representative genre of contemporary art (227). At the same time it seems Hooton had understood this in a related, yet different way: the treatment of the arts as distinct was no longer possible – this is a persistent theme of his writing – and, because the arts include all workers, it precipitates an anarchist-dictatorship over things, where the ‘engineers must rule’ (21st Century, n.p.). Furthermore, Hooton’s philosophy drew upon a stark distinction between ‘man’ – by which I take him to mean ‘people’ – and things, which furthermore places him at odds with the dominant trajectory of trans-humanism and a sci-fiction and theory community, represented by writers like Ursula K LeGuin and Donna Haraway, since the 1970s.1 So, while the Cantrills focused their attention on ‘light energy’, their interest in the material upon which they worked was informed by their actions upon it, rather than within it.

From the letters Hooton wrote to Corinne Cantrill, now in the State Library of Victoria, their initial contact was based around the shared interest in publishing 21st Century. Cantrill is described as the ‘saleswoman’, while her partner at the time, Jacob Judah, contributed his ‘Episodes In A Life’ to the same issue in which Hooton calls for this ‘dictatorship’. Sculptor Robert Klippel also contributes an essay to the issue titled ‘Direction In Design’, suggestive of the idiosyncratic response to technical domination pursued by Hooton and his confrères. ‘The most important thing for us is still, as always, self theoretical clarification,’ Hooton writes to Corinne, concerning the second issue of the journal, on August 1, 1957. ‘I know we mustn’t assume our superiority as an elite for all time, but we must recognise there is universal value in our work, and keep it pure – no matter what the opposition thinks it thinks.’ What the young Corinne Joseph thought of Hooton’s ideas – she recounts growing up as a Jewish girl both during wartime and white Australia in her autobiographical film In This Life’s Body (1984) – we can only imagine was both terrifying and galvanising.2 Clearly Hooton was concerned with the material world of things, which he saw a separate from the human, but his diction resonates with language that can only be read as tending towards fascism, irrespective of its parodic re-deployment towards ‘things’, rather than its more sinister applications towards the Other.

In Issue 5 of Cantrills Filmnotes a section dedicated to ‘our grandfathers’ (‘as Garrie Hutchinson called them’) begins with a quote by László Maholy-Nagy: ‘Inability to use a camera will in the future undoubtedly be regarded a analogous in point of illiteracy as inability in the use of the pen …’ (n.p.) Hooton’s modernism, in spite of its apparent simplicity, was of a type perhaps closer to the German writer and anarchic soldier, Ernst Jünger, a paradoxically anti-humanist theorist of ‘the worker’ as envisioned following his experience of the trenches in the First World War (see: Jünger). The ‘Melbourne Vortex’ of interest in Ezra Pound, while the poet was interred at St Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, suggests another line of enquiry (Philrose, 179). After Slessor’s endorsement of the Chauvels’ attempt at telling the colonial history of Australia, with Heritage (Expeditionary Films, 1935), what happens to what Mead terms ut cinema poesis in the newly self-conscious country (no-longer Britain), and once filmmakers begin to own the means of production for this new medium, is truly anarchic. That Slessor’s Five Bells is read as cinematic poetry by Mead, however, says more about the difficulty of writing poetry in the age of cinema than it does about filmmaking.

Figure 5: The first page of Harry Hooton, Anarcho-Technocracy: The Politics of Things. Chippendale, N.S.W: self-published, c.1940, 4pp. ROSSpam 858. Canberra: National Library of Australia. The reference to the larger work is to Hooton’s Militant Materialism, which remained unfinished at the time of his death.

Hooton was born in Doncaster, Yorkshire, and arrived in Sydney on the 28th of October 1924. His first writings were published in 1936, the year after the first full-colour film was released in Australia, Becky Sharp (RKO Radio 1935) directed by Rouben Mamoulian (Mead 64). In a 1943 essay titled ‘Problems are Flowers and Fade’, Hooton defines art as a vanguard pursuit linked by poetry to enquiry, as ‘searching for what is new,’ and philosophy as ‘searching for what is true’ (25). The simplicity of Hooton’s bare constructions are often disarming: ‘Humanity is no longer worthy of our enquiry or representation’ (Ibid). It is a refreshing take, to revisit a poet who believed in being, rather than becoming. Contemporary poetry today still speaks of learning to speak, of language emerging. Ariana Reines writes of the quest for a 21st century epic verse: ‘we have not yet learned how to use language’ (interview with Eric Newman and Katie Wolf). Potentiality has been a key strategy for contemporary thought. Reines uses the poem as a vehicle to point to an ambiguous and partial temporality, ‘of watching one / Another break down’ (Book of Sand, 7). In 1958 Hooton had claimed: ‘Language is not eternal. It will be replaced. We are not going to talk forever’ (Hooton, Full Cry 5 n.p.).

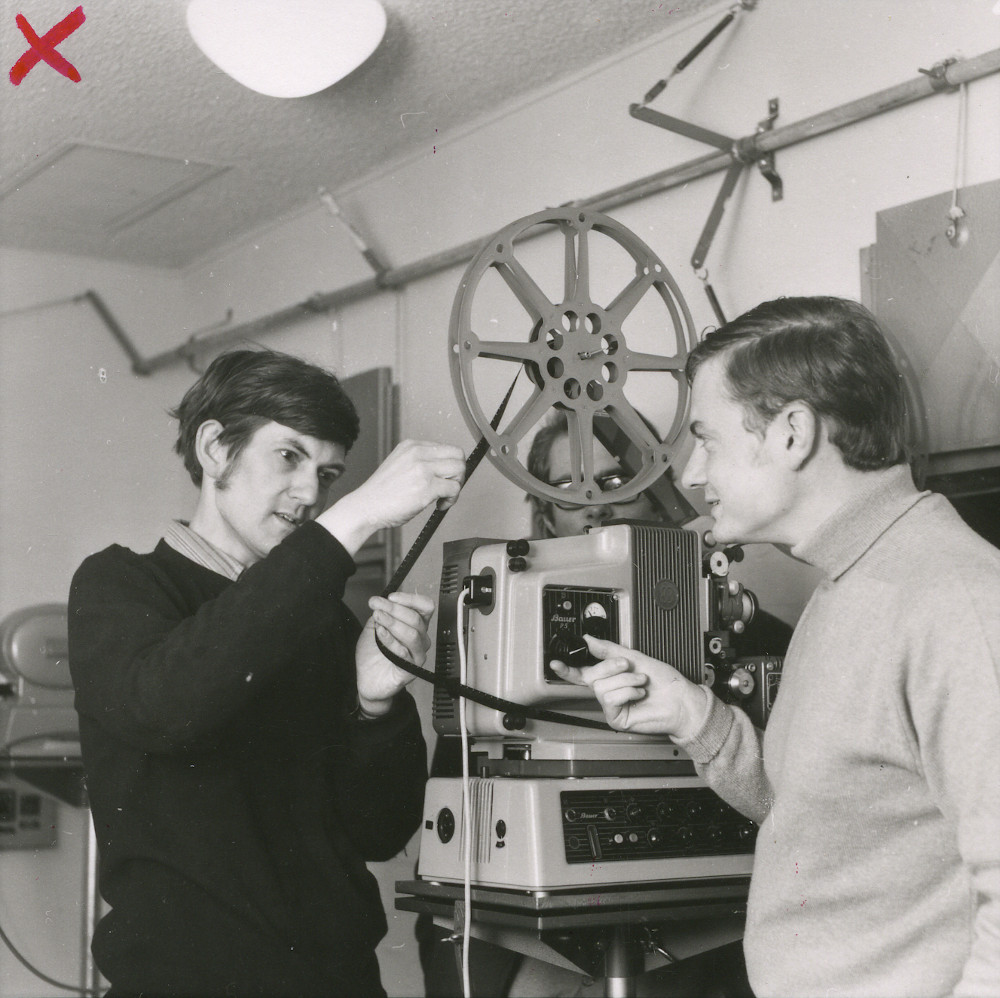

Figure 6: Arthur Cantrill and Andrew Pike in a projection booth at the Australian National University on the 20th of May, 1969. This photo was taken just after Arthur Cantrill took up an ANU Creative Arts Fellowship in filmmaking. Australian National University, Canberra. ANUA 226-729-3.

In an interview from 2014 Corinne describes the Filmnotes as, among other things, ‘focusing on work from the Pan-Pacific region’. In the 1970s their encounter with the arts-collective Bush Video, and multi-media artist Joseph el Khourey, as well as their turn to pre-colonial and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures through the anthropology of Baldwin Spencer, meant a turn away from the doctrinaire avant-gardism of their earlier work. Spencer’s films from 1900/1901 provided an archival model for making work that was no longer about novelty. El Khourey had suggested these films to them, and their encounter with idiosyncratic cultural historians like Harry Smith during their time in the US (between 1973-75) had alerted them to the broader context in which their work was situated. Andrew Pike, whom Arthur Cantrill had first worked with at ANU in 1969, described the work of Japanese artist Terayama Shuji as an example of the ‘intermedial creative practice’ in the context of a ‘Pacific community of poetry’ made explicit for the Cantrills in the mid-1970s (Figure 6) (Pike cited in ‘Little History,’ 413-4). Things began to shift away from Hooton’s hard-lined vision of the future, to less concrete visions of cultural practice.

- In a letter to writer Marie Pitt, written in October 1942, Hooton describes a conversation he had with Miles Franklin where he described himself as a feminist, despite her general dismissal of his intellectual project. Hooton cited in Soldatow, Poet of the 21st Century, 1990, 13. This appears in stark contrast to the position of the Futurists, who openly decried feminism in their Manifesto of 1909. See Lucia Re, ‘Futurism and Feminism.’ Annali d’Italianistica, 7, Woman’s Voices in Literature (1989): 253-272. ↩

- Jon Stratton writes of the ‘ambivalence’ of Jewish identity in Australia during the white Australia policy, which is further confounded by the legitimation crisis of Australia as a settler-colonial nation-state. See Jon Stratton, ‘The Colour of Jews: Jews, Race and the White Australia Policy,’ Journal of Australian Studies, 20 (1996): 51-65. DOI, online. ↩