Figure 4: ‘Cinemapoetry at the Maze,’ Cantrills Filmnotes, 1 (March 1971; 2nd edition 1988), 6.

Figure. 7: Garrie Hutchinson photographed by Fred Harden during the BLAST CINEMAPOETRY event, photographed by Fred Harden at The Maze, 1971. Cantrills Filmnotes, 2 (April 1971).

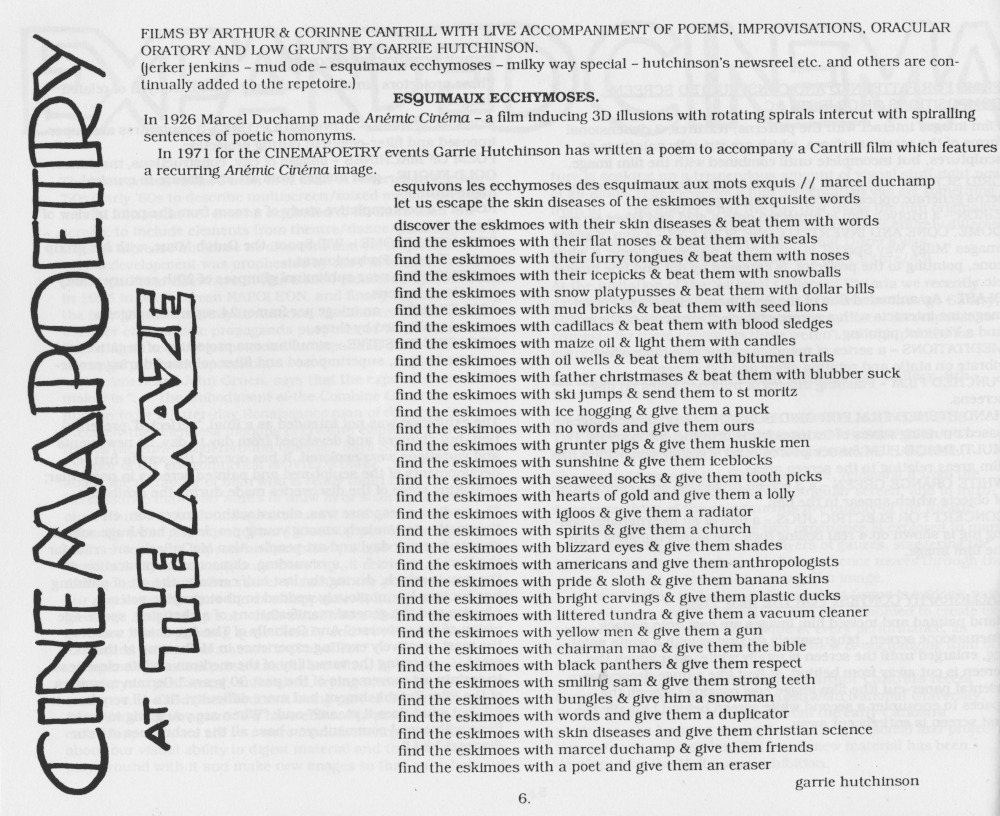

‘Cinemapoetry’ appears in Issues 1 and 2 of the Filmnotes, initially described as: ‘films by Arthur & Corinne Cantrill with live accompaniment of poems, improvisations, oracular oratory and low grunts by Garrie Hutchinson’ (6). Taking place on the 18th of April 1971, almost exactly a decade after Hooton’s death, the performances were a part of the 18-week season titled ‘Living Cinema’, which the Cantrills were running on the quieter Sunday night-time slot on the The Maze’s otherwise lively calendar of music and performance events (Figure 4).1 In the second issue of the Filmnotes, a 21-year-old Hutchinson, who would go on to become a celebrated poet, editor and oral historian of ANZAC soldiers writings during war-time, can be seen mid-performance in a photograph taken by Fred Harden (Figure 7). The second issue dedicates further space to remembering Hooton and after introducing his work (‘for Hooton, it was vital that men made war on matter, rather than on one another’) the text shifts seamlessly into a detailed, technical description of the Cantrills’s film, Harry Hooton:

The film is applied Hootonics, based on Hooton’s dictum ‘Art is the communication of emotion to matter’ and it explores many techniques, from the highly technological computer image sequence, programmed at the CSIRO Division of Computing Research in Canberra, to the technically simple hand-printed images mentioned above. (Cantrills Filmnotes, 2, April 1971, n.p.)

The text also suggests Hooton was ‘years ahead of his time,’ and makes the now somewhat quaint claim that he was ‘an Australian Buckminster Fuller,’ before referring to the significance of his ultimate work, It Is Great to Be Alive. The collection in which Hooton’s ‘Poetry’ first appeared was published by Margaret Elliott in 1961. Hooton saw the proofs of it on his deathbed.

Elliott is the other figure listed in 21st Century (credited with Design & Layout) who would also loom large for Australian cinema from the 1970s onwards. Hooton and Elliott had lived together at Potts Point throughout the 1950s, after first meeting 1952. When Elliott later married (property developer and restauranteur Leon Fink), she changed her name to Margaret Fink. Under this name she began to produce adaptations for the screen, such as David Williamson’s The Removalists (1975) directed by Tom Jeffrey, and Miles Franklin’s My Brilliant Career (1979) directed by Gillian Armstrong.2 By this time, perhaps buoyed by the avant-garde experimentalists who had become a feature of Australia’s expanding arts community, Australian cinema was entering a new phase. Films like Stork (1971), directed by Tim Burstall and with a debut performance by Jackie Weaver, linked Carlton’s La Mama theatre to local, yet ambitious filmmaking productions. Significantly, Hooton and Fink (as Margaret Elliott), had also first come into contact through the Push in Sydney. As a much mythologised bar-scene for philosophers, political and social theorists, Hooton is cast as opposed to other figures of the day, such as the Professor of Philosophy, John Anderson, an enthusiast of James Joyce and Scottish founder of the Libertarian Society, who taught at Sydney University from 1927-1958 (and whose arguments Hooton would call ‘Andersonian Shit’).

Other figures associated with the progressive socialist politics of the Push, like John Flaus, would begin to appear in the independent films emerging from the Sydney arts scene – in films like The American Poet’s Visit (dir. Michael Thornhill, 1969) – and on stage at La Mama in Melbourne. Flaus eventually came to Melbourne and created Film Buffs Forecast, a weekly review of cinema for 3RRR FM radio, which he co-hosted with Paul Harris in Melbourne beginning in 1980. The Cantrills had also emerged between these two ‘universes’, Sydney and Melbourne, among many more (Brisbane, London, Canberra). Between politics in the Australian pubs and the representation of life in Australia on the stage, their focus was directed towards the materialism of their chosen art, and at the intersection of thought and action that had to remain a possibility for film as a medium of mass communication.

Intermedia

On the 27th of July 1983, a special radio interview programmed by critic Adrian Martin and artistic director Sue McAuley was broadcast on 3RRR FM, and later transcribed by Kris Hemensley for his ‘small press’ journal H/EAR. Discussing the shared commitment to activity which characterised both the Cantrills Filmnotes and the burgeoning literary scene in Melbourne during the 1970s, Hemensley and Corinne Cantrill reveal their motivations behind the work they have been concurrently undertaking in publishing and performance (H/EAR, 5, 501-16). Given the international scope of both figures’ work, there is something which remains distinctly local about the competing forms of modernism that they develop here.

Hemensley in particular raises the notion of what he calls ‘inter-medial art activity’ and the recording and documentation of ‘what’s happened to them over the years – so there’s an archival aspect’ (ibid. 403). He goes on to describe the written texts of filmmaker James Clayden’s feature-length film Corpse (1982) as ‘a kind of automatic, spontaneous writing’ which he had thought to include in H/EAR’s fourth issue, and reflects on how someone ‘connected with the local avantgarde’ had produced ‘a major new Australian film’, and in H/EAR they’d thought to celebrate that (Ibid. 403-4). The question of what this impulse was, had been tentatively formulated in 1966 by Fluxus artist and publisher of the Something Else Press, Dick Higgins. For Higgins, intermedia was the way in which the arts could coalesce around an idea or mood that was, by the end of a decade marked by a massive technological and cultural shift, intoxicating. Higgins went so far as to call it an ‘uncharted land’.3 ‘Expanded Arts’ was another term that came to be used to describe the promiscuity of practices helping to produce new horizons for the arts of the 1960s and 70s. But it is this term – intermedia – which pops up again in Hemensley’s discussion with Corinne in 1983. Significantly, Hemensley’s suggestion of a ‘New Australian Poetry’, in 1970 had sought to internationalise the potential of what he saw as the ‘little mags’, even as he left for England (Meanjin, 29, 120). His parting shot: ‘In Australia there is a battle [with] anti-Anti-Intellectualism before one even arrives at the stage of anti-intellectualism ie the Academy’ (Ibid). The answer, he believed, was in the ‘open communications’ that contemporary technologies were making increasingly possible (Ibid 121). As Hemensley departed, the Cantrills had just returned from Europe and their thinking about film had very much shifted from the work they had been pursuing when they left. Shared sentiments were apparent, however, with Arthur publishing ‘Towards a New Australian Cinema’ in Westerly, the quarterly published from the University of Western Australia, in 1972. It begins by describing their dismay at the ‘retarded film sensibility’ of Australia in contrast to London, and ends by referring to American architect and system theorist, Buckminster Fuller’s notion of a ‘negentropic system’ as a synonym for lively activity. Again, open communication is determined to be what was needed most for the ‘new’ arts. Coupled with Arthur’s plain-language formulation at the centre of the text, their intentions are clear: ‘Many of us want a radical new society’ (27).

Over the New Year holiday 1967/8 the Cantrills had attended the EXPRMTL 4 Film Festival at the Casino in Knokke, Belgium, which was directed by the revered cinema curator Jacques Ledoux. It was this experience perhaps more than any other that had galvanised their filmmaking, Corinne describing it as a ‘turning point’ in their careers (in ‘Astronauta Pinguim interview’, 2014). Returning to Canberra the first person they had thought of, rather than just pursuing the newly ‘open communication’ apparently flourishing amongst their contemporaries, was Hooton. While encounters with now canonical figures like Michael Snow, Yoko Ono, and a young Harun Farocki, had shown them the possibilities for art and politics were open, the conditions they found upon their return to Australia were, of course, notably different. Xavier Garcia Bardon has described Ledoux’s singular vision for the festival in the following way:

For Ledoux, avant-garde film couldn’t be placed separately from parallel, formal projects in the other arts: it could only be understood in relation to music, literature, the visual arts, and only at the heart of a network linking all these disciplines. (Bardon)

The last line of text in the first issue of Filmnotes made demands to its attentive readers: ‘Support the Alternative Cinema!’ In this way, the alternative cinema can now be understood to be the ‘network’ linking the formerly academicised disciplines like music, literature, and painting. In a way that precedes their later turn to the environment, intermedia formalises the ecology of the arts as performed and recorded within the habitual spaces of the artists own lives.

What seemed to require a renewal of the Australian arts, detectable in Hemensley’s polemic in Meanjin, were the institutional controls over the dispensation of this cultural life. Unlike Hooton, who detested the liberties afforded by the Joycean language games that were championed by Anderson and his acolytes – perhaps because of the inaccessibility of the old-country idioms – the provincialism of modern Australia’s attempts to aspire to the heights of European aesthetics, despite the obvious geographical and cultural disconnect, had led to a form of anti-modernism which had lingered from its significant ‘events’. The Ern Malley affair, for example, still only now coming to shift from ‘apocrypha to canon’ (Mead 17). While Hooton’s chap-book Things You See When You Haven’t Got a Gun (1943) was positively reviewed by Max Harris in the same issue of Angry Penguins that the Malley poems appeared, it was clear that any alternative idea of Australian literature was butting up against its wholesale importation by the educated elites.

The Malley ploy by James McAuley and Harold Stewart, which also draws in the notorious and future Governor General of Australia, Sir John Kerr, was inspired by A.D. Hope, with whom Hooton, along with Garry Lyle, had issued a set of poems in the preceding year (see Roff). No.1 (July, 1943) includes Hooton’s ‘Geometry for Beginners,’ which reveals something of the tack Hooton had set for himself, eventually setting course for a far different location than many of his contemporaries.

Now for some ambiguity: Nietzsche. Will to power - over what? Over machines? By all means. Over men? As means to an end? What rot! Means are the ends. Why return at all to men? Machines are the end! And the means to mightier men! (Hooton, A.D. Hope, Garry Lyle, Harry Hooton , n.p.)

With Garry Lyle and John Cremin, Hooton had organised to edit an anthology of Australian poetry in 1941, coincidentally in the same year as his first collection of poetry was published under the somewhat inscrutable title, These Poets.4 Titled Dawnfire: Selections from some modern Australian Poets, it was this text – alongside his own efforts – that marks Hooton’s first successful foray into publishing poetry in Australia.

Hope would eventually deride Hooton’s shift into a form of philosophical and didactic poetry as cultural criticism, when Power Over Things was published by the Inferno Press in San Francisco, 1955. Writing in Meanjin Hope called Hooton’s work ‘Anarchism with a Science Fiction face-lift,’ commenting that even as he looked to universal themes, there was something hopelessly provincial motivating his work (575). Yet Hope’s attempts to cut Hooton down to size no longer appear so cutting today. A series of Reith lectures on ‘Art and Anarchy’ by Edgar Wind in 1960 have since been republished three times. And recent work in Italian philosophy appears to recall something of Hooton’s ‘Anarcho-technocracy’, for example when Giorgio Agamben writes on the possibility of thinking beyond the enframing of life under an increasingly authoritarian form of technocratic capitalism:

a clear comprehension of the profound anarchy of the societies in which we live is the only correct way to pose the problem of power and, at the same time, that of true anarchy. (77)

To this imperative could be added the recent interest of poets working on the ‘alternative’ histories of the 20th century, who have found in Hooton a curious figure to re-engage with. Poet Astrid Lorange, for example, has written cautiously of discovering Hooton for Jacket2, and A J Carruthers included Hooton in his ‘Lives of the Experimental Poets’ series published in the same journal.

At the turn of the millenium, artist and curator Ruark Lewis had linked Hooton with other poets writing of Sydney’s Kings Cross for the early online journal CrossLines. Lewis makes Hooton the link between poets Anna Couani and Kenneth Slessor. The latter’s poem Five Bells (1939) is a ‘portrait’ of a friend drowned in Sydney Harbour, below the Cross that remains as a ‘nodal point of transits’. The strong sense of the visual symbolism that motivates these poems, though more distant in Hooton’s work, draws us back to the encounter between film and literature which had proceeded the cinemapoetry event in Melbourne in 1971, and furthermore suggests the ‘inter-medial’ relationships cherished by Hemensley and the Cantrills when reflecting upon the period of ‘glorified correspondence’ that informed the early stages of their respective publishing projects.

- An advertisement for the series on the final page of the Filmnotes lists the event as beginning at 8.30pm on Sunday nights at The Maze, 376 Flinders St, near Queen Street. ‘Informal workshop atmosphere, experimental projections, film events, film involvement with poets and musicians. Food, coffee, drinks available. ADMISSION one dollar.’ Cantrills Filmnotes, 1 (March, 1971): 12. ↩

- Hooton had met and began a correspondence with Miles Franklin in 1942. Any link between Hooton, Fink, and the successful film adaption of My Brilliant Career has not been able to be established, however. See Poet of the 21st Century, 1990, 15 n56. ↩

- Dick Higgins, ‘Intermedia,’ Something Else Newlsetter, Vol. 1, No. 1 (February 1966): n.p. Reprinted in Dick Higgins Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press. Edited by Steve Clay and Ken Friedman. Catskill, NY: Siglio Press, 2018, 25-8. The ‘Intermedia Chart’, published by Higgins in 1995 does includes cinema as a part of the Venn-diagram and within the Fluxus bubble. However, film does not appear, even though a number of ‘bubbles’ contain only question marks. See Higgins, Intermedia, 2018, 2. ↩

- Given the number of studies dedicated to the Ern Malley hoax, it is surprising how little Hooton appears in the histories of Australian poetry, giving his proximity to the affair. His appears once as ‘the anarchist poet’ in Michael Heyward, The Ern Malley Affair (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1993), 49. This is all the more odd given the epigraph to Heyward’s book, provided by Harold Stewart, claims ‘All Australians are anarchists at heart’. And despite the attention paid to Stewart’s mentor and Hooton collaborator A.D. Hope, Hooton does not appear at all in Paul Kane, Australian Poetry: Romanticism and Negativity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). ↩