Beyond the Ohlala Mountains: Alan Brunton, Poems 1968 – 2002

edited by Martin Edmond and Michele Leggott

Titus Books, 2014

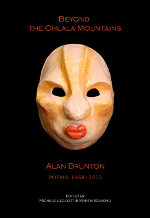

The mask on the cover of ‘Beyond the Ohlala Mountains’ suggests that there’ll be some odd theatrics inside the book. It’s a plain papier-mâché mask of a slightly jowly head with a bulbous nose and a pair of puckered, pouting, full red lips. What does it express – is it a superior sneer? Is it bourgeois disdain? Is it about to say ‘oh là là’? The mask was made by Sally Rodwell, the now-deceased partner of the New Zealand poet collected here, Alan Brunton. It was made for a theatre work called Cabaret of the Unlikely that was performed three years after Brunton had died at 55, in 2002.

Alan Brunton wrote ‘I adopted strangeness as my routine’ and that line sums up the poetry placed between photos of masks, figurines and puppets in this substantial memorial collection edited by Martin Edmond and Michele Leggott.

The poems are ‘of their times’ in the decades 1968 until 2002, and give an impression of the poet as an adventurer, a romantic, a traveller and an optimist. As a scriptwriter and performer Brunton worked as an editor, director, performance tutor, and community arts worker. He also edited a couple of magazines and is well-known in New Zealand as the 1978 co-founder (with Sally Rodwell) of an experimental theatre group called Red Mole.

It follows, then, that many of the poems are performative and made from a kind of heroic story-telling imagination. These are poems that traverse Day-of-the-Dead deserts in Mexico, or impossible mountains, or big rivers like the Mekong. In a single poem the scene can relocate from, say, Burma to Germany or Portugal to Algiers, from the Silk Road to Spain. The poet is an irrepressible seeker, urged on by curiosity and a kind of reckless energy to check what’s happening round the next corner of wherever.

In the poem ‘And’, the adventurer asks ‘so what do I know I did not know yesterday? / What do I see? / I see the City glow when lightning slashes the antennas’ and Bob Dylan’s early repetitions come to mind. From early to late, these poems do have traits that are reminiscent of the Beats, especially Kerouac. Brunton identifies with and champions the downtrodden. In ‘Song of the Emigrant’ the first person is plural – ‘…we are so few / tagged with plastic IDs/ and that day we spend / as we spend each day / awaiting night and our fate / and we spend the night / badly dressed / stripped of our island / stripped of our sky / without representation in our distress…’

There are some early 1970s poems that emulate Australian or, more correctly, Sydney poetry’s take on personism. ‘The View from Nigel’s House’ begins

Harry, I'm in Balmain. From here Sydney is all geometry and a green flower flies in the sky above Woolloomooloo, and I walk at the double through these streets

He also visited Melbourne in 1970 and wrote a poem, ‘Walking down Collins Street with Charles Buckmaster’, that’s imbued with romantic beatnik air –

Walking down Collins Street in the middle of the night and smoking Chinese Elm leaves that Charles has rolled tight in-between 2 skins, suddenly, it's 3 a.m. I've got a very moderate buzz...'

The poem becomes unhinged as the hallucinogenic elm leaves take effect and just before ‘Flames shoot from the windows of Melbourne’ a possibly-imaginary woman, Sophia (the wise), who ‘carries tobacco between her legs’, incites some dogs – ‘Dogs, go on, go on, / bite his penis!’. The poet runs off to catch a tram. What was IN those elm leaves? These poems are in the section comprising 1970-73 called, after Jack Kerouac, ‘On the Road’.

There are numerous dramatic characters and situations throughout this vibrant collection. A late poem, ‘Fever’, extols –

'The sage lives in a tower where bits of saintgod fall on him at a million degrees from magnetic clouds every 27 seconds he has brilliant teeth / and skin that never grows old; saintgod does nothing since our village abandoned Truth except hang out on the precipice, waiting for us to find something for him to do; our century is saintgod's obituary...'

Alan Brunton often uses this technique of setting up a prologue to engage the reader.

The tone and energy of this poetry are consistent through the decades. Alan Brunton’s life would have developed in varying ways as he (as I imagine anyway) charged off on different trajectories – in relationships, becoming a father, gaining recognition, in travel, in theatrical performance and so on but the poems, even in their particularly fantastic or offbeat accounting, maintained an optimistic and reliable similarity.