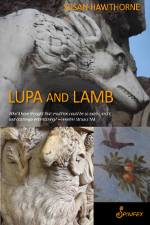

Lupa and Lamb by Susan Hawthorne

Spinifex Press, 2014

Lupa and Lamb is a beast of a collection – it spans literally all of time and features every woman that has ever lived. Ambitious is not too strong a word. Curatrix, our guide and commentator, leads us through archives of lost women’s texts on the way to a party held by the Roman Empress Livia Drusilla. It is through this trail that Lupa and Lamb tells women’s histories and their multiple, often contradictory roles in family and society. Plurivocal translations speak in Latin, Greek, Sanskrit, Italian, among others. Though largely focused on Roman and Greek mythology, the text’s characters span from the goddess Demeter to Monique Wittig, whose Les Guérillères is quoted at the beginning of this book: ‘There was a time when you were not a slave, remember that … Or, failing that, invent.’

Lupa and Lamb’s title introduces us to women’s dual, if not multiple, identities or roles under patriarchy. Women are both lupa – she-wolf or prostitute (an archaic term considered a slur against sex workers that I use here only for the sake of translation) – and lamb, suggesting the whore/Madonna dichotomy.

she is the lamb in the sheepfold wolf in the forest virgin violated lupa levitated madonna whore lesbian lover her transitoriness is as permanent as memory and invention (pg. 146)

This sense of multiplicity appears throughout the text, and the many shifting speakers remind me of DuPlessis’s notion of a text’s ‘multiple centres of attention’ and the numerous erogenous zones of women in Irigaray’s This Sex Which is Not One. In addition to her roles as lupa and lamb, the woman has what DuPlessis called a ‘both/and vision’ of the world – that of the human being (which defaults to man) and of the woman. History has never been on her side of the story.

The text documents men’s crimes against women. ‘Ilia’s dream’ recounts her rape by the god Mars and the abandonment of her father, evoking the silencing of survivors and victim-blaming under patriarchy: ‘he does not comfort me … he kowtows to the one who calls himself god/as if this excuses rape’ (pg. 21). In ‘craft’ attempts are made to erase women from history, they ‘unraveled our stores/wiped the slate clean/smashed the pots’ (pg. 106). This poem is one of the simplest and most evocative poems of the collection, also demonstrating the significance of lamb’s wool in women’s spinning. We are shown how craft – and activities shared amongst women – became a medium in which for women to communicate their histories:

so we kept silent

we avoided the high arts

…

craft saved us

we spun and sewed

wove patterns on fabric

cooked and healed

drew on pots

sang and told old wives’ tales

to our daughters (pg. 106)

Contemporary feminists often joke of an unconscious hive-mind of collective feminist thought, and Lupa and Lamb certainly conjures this romantic sense of a shared feminine temporal plane. The lost texts are fragmented, incomplete and roughly translated: ‘woman dilly bag carries/cruch time comes/she [?] the mountain path sees [follows]: moon sets’ (pg. 11). These incomplete poems and the mystery of the ancient Etruscan language, combined with the building chanting – ‘our million mouths singing’ (pg.147) – of the party’s guests suggests something pre-language and pre-symbolic, in the Kristevan sense, of a place before and outside of patriarchal order.

There is a recurring theme of women’s laughter in

laughter ricochets around the circle infecting each one of us Baubo makes Demeter laugh again Medusa laughs her head off (pg.145)

– a triumphant reference to Helene Cixous’s seminal The Laugh of the Medusa. Again in ‘craft’: ‘we were ignored/we were inventive/and we laughed’ (pg.106). Lupa and Lamb embodies some of the most romantic, erotic and intellectually satisfying elements of second-wave feminist aesthetics, primarily that of écriture féminine – telling women’s stories and embodying ‘feminine’ bodily traits. The text is fluid, cyclical, untamed and non-linear.

At times however the poems feel as though the history and mythology has been too stuffed in. Any attempt to call on the lives of every woman that has ever lived into one book is a massive undertaking – one that arguably will fail – so at times Lupa and Lamb does feel cramped. The scope of the work could easily have filled an encyclopaedia more so than a 170-page book of poetry. Despite this, there seems to be little variance in the kinds of women represented. The more recent factual figures at the party – Mary Wollstonecraft, Susan B Anthony, Eleanor Roosevelt – are white activists and political figures. Conspicuously lacking are the sex workers (in a collection referring to them in its title), the trans women, the punks. And while there were the notable inclusions of the girls speaking in Sauraseni and Mahārāstri Prākrits, and the host of ethnicities of women arriving at the party, I can’t help feeling an uneasiness – a bristle at a hint of colonialism – when Western writers seek to incorporate all the world’s (well, half the world’s) history.

This collection is confronting when it details the history of unspeakable oppressions and injustices throughout the ages. But Lupa and Lamb is also affirming and joyous in its celebration of female kinship, love and camaraderie.

This is a vast, instructive and impressive collection by Susan Hawthorne, and a grand addition to her oeuvre. Part mythology lesson, part spirited imaginings, we are immersed in many chapters in the story of women as we laugh in the faces of those who seek to silence us.