Melbourne-based Benjamin Laird writes computer programs and electronic poetry, which he discusses here in the first of a new, occasional blog series looking at the writing practice of contemporary Australian poets. Laird is also undertaking his PhD at RMIT, researching biographical and documentary poetry in programmable media. He is Site Producer for Overland and Cordite Poetry Review. One of his in progress-works is called ‘They have large eyes and can see in all directions’. The reader enters a digital space which appears like a curved diorama, then enlarges to show itself to be like a virtual circular room. The floor and walls are mosaics of text and archived newspaper articles on William Denton, a 19th-century geologist, spiritualist and explorer, whose writing and biography inspires Laird’s poetry here. Some of it hangs and can rotate, in 3-D space, like an Alexander Calder mobile. The reader can zoom in on the many sections to read it. The title comes from a description by Denton’s sons, 19th-century naturalists and collectors, who described lyrebrids (which they were hunting in Victoria) in these terms. The work will be viewable soon at a new website currently being built by Laird.

How do you define electronic poetry? And how did you come to work in this form?

The extremely short answer is where a computer is intrinsic to the material properties of the poem, either where a computer is used to generate poetry, or where a computer needs to be used in order to present the poetry. Even though a lot of poetry is published online and so is digital, it’s not useful to see that poetry as electronic, because it could be just as easily printed out. The definition of electronic poetry also folds out to the culture of those things related to computers.

If we look at Australian-based poets that have worked the area, there is John Tranter with Different Hands (FACP, 1998) where he used software to generate experimental, poetic fiction. There’s Mez Breeze, she writes codework. She has her own form of poetic language, called Mezangelle. And then there is earlier web-based work which began in the 1990s, ‘geniwate’ (Jenny Weight) and, at that time, Komninos, and, currently, Queensland-based Jason Nelson who is very well established internationally. This isn’t a complete list – there are many other Australian poets experimenting with what computers have to offer them. And in a lot of ways the history of the computer also has a parallel history of poets who used computers to write poetry.

It is interesting to see how even the most seemingly benign elements affect how poetry is written now. We are all constraint bound by the media we work in, so the Microsoft Word document – and in Australia its A4 page – that a number of poets are confronted with suddenly becomes a constraint. So people will think about starting to work to margins, expanding what gets printed out. If a journal size is a bit smaller than usual, the poem has to find some compromise on the actual page. When you are working in computational forms, you don’t have the A4 page as a constraint any more, but you have it in the constraints of what comes with the programming language, how you can exploit what a browser can do, or what a desktop machine can do if you are making an app. Phone app poems have constraints of the phone itself. So the actual writing of poetry becomes ‘what can I do within this media?’ – whether it’s in print or whether it is in an electronic form.

A shift in technology drives changes in poetry. The typewriter, for instance, changed poetry, let alone technologies previous to that.

I think it is a very strange thing – there are a number of programmers who are also poets who don’t, say, make digital work and who I think are exceptional … poets like Maged Zaher, an American-based Egyptian poet. He encapsulates the three things I am most interested in: politics, programming as white-collar work and poetry.

These are skills that are meant to be economically productive, and then you turn them into poetry. I started writing electronic poetry five years ago after a long break. It’s been an oscillation between technology and then literature, and then trying to synthesise them.

What is your current poetry project?

I’m writing a collection of biographical electronic poetry works on William Denton, who was a 19th-century geologist, who travelled internationally giving public lectures on evolution and the formation of the world. He was a spiritualist, so he also toured the spiritualist circuits addressing those audiences. He was also a political radical and advocated for women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

One of the main things he was known for was producing, with his wife, a three-volume work called The Soul of Things. (My project is called on The Code of Things.) It was on psychometry; the idea that objects have memories, so if you hold an object, you can see what it has experienced. The project will be a website, progressively developed as part of my PhD with all the works housed here.

He was English-born but lived most of his life in the US. He toured Australia and New Zealand from 1881 and died during a Melbourne Argus expedition to New Guinea.

His sons were collectors of skins and fossils. They had a 19th-century attitude to the environment, which is to collect it. They hunted lyrebirds in Victoria, for example, which triggers subject-matter for one of the work.

The whole project is an attempt, within the six works, to represent William Denton, including his relationship with his eldest sons, and to use poetry in programmable media to create a biography.

Do you think electronic poetry is misunderstood in the literary community by both other poets and readers?

No, I don’t think so. The biggest problem is that there is not a lot of work out there. Ideally, there would be a lot more people writing this kind of poetry so it would be more natural to see it in literary journals. Last year when Overland published an electronic poetry issue it got really great responses by people who read the work and by others inspired by it. One of the challenges of creating this work is, because it’s not seen as frequently, then people who would otherwise like it are not so sure of how technically feasible it is to publish. Likewise, poets inspired to write electronic works find it difficult to know where to start.

Were there early, formative moments which influenced your writing of poetry?

I think it’s a really interesting question for poets to consider. There are many ways to work with language … so the fact that people choose poetry fascinates me because I think it is the most intimate relationship you can have with language. When I was three, I lived with my grandparents for a year. They spoke Tamil, but also spoke English (my family background is Sri Lankan). I went to a local school there (in Malaysia) and nobody spoke English. At least that is how I remember it. Only having one language in order to access the world, where that was no longer useful to me in relation to other people, was a foundational experience in terms of clarifying my idea of what language was.

So it created a sense for me that language was a thing, a material thing, and I guess the next step, beyond-using-language-naturally, was when I began to program. I had a computer quite young and programmed in high school enough to know that we had other forms of language which actually did things to machines. So there’s a sense that poems are like machines, they’re sculptured language, they’re assembled language.

What is your rhythm for writing? Do you work at set times, on set days? Or is it more organic for you? Where do you write?

I don’t have set times or rhythms in terms of working on poetry. I start with a notebook, starting with the initial poem, even if it’s an electronic work, then I will oscillate between writing and designing, assembling and programming across a work. I might also go back to the notebook.

For me, I find creation really interesting when writing a poem – you write the words, then you write it into the space, then you write the time around it. Everything needs to be meaningful in that relationship, the movement, the temporal qualities, the kinetics of the work, the spatial (where it actually occurs on the screen or within the digital space of the poem), and the semantics of the actual language involved. I mostly work at (pointing to) this desk (in doctoral offices at RMIT).

How do you keep alert for writing poetry?

I read poetry, print and electronic, as much as possible. And reading other things too: computer books, literary criticism, computer code, newspapers and corporate copy.

Can you name two or three poets (or particular poems) whose work is important to you?

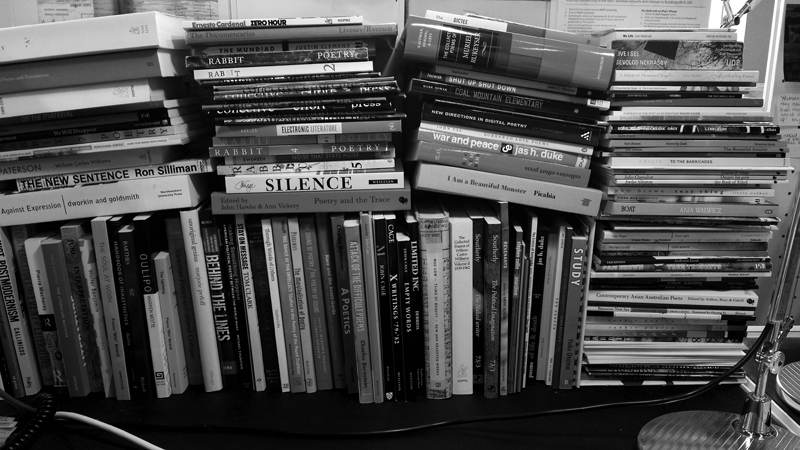

In three poets I’m not even sure I could cover all the kinds of poetry. So I send instead this photo of the current collection of books on my desk. More specifically, though, I’m not sure where I’d be (in terms of poetry) if I hadn’t read Ania Walwicz, TT.O or Pam Brown.

At the moment I’m looking at quite a lot of documentary poetry and so recently read Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead, which is an incredible long poem in so many ways. And Jessica Wilkinson’s Marionette is a fantastic book that intersects the experimental with the biographical.

On the electronic poetry front, the works Nick Montfort and JR Carpenter were very significant when I started mixing code and poetry.